SWOV Fact sheet

advertisement

SWOV Fact sheet

Fear appeals and confronting information campaigns

Summary

Fear appeals or confronting information campaigns confront people in an often hard and sometimes

even shocking way with the consequences of risky behaviour. This can have a positive impact on the

attitudes and behavioural intentions of the target group, but only if key conditions are met. Those

conditions are that the information does not only evoke fear, but also informs the target group

individuals of their personal risk and provides them with feasible and effective behavioural alternatives.

However, it is uncertain whether achieving a behavioural effect always requires the emotion of fear.

Confronting information campaigns may also have negative effects: the target group can deny,

downplay or ridicule the information message, or it can elicit stronger intentions to engage in the risk

behaviour.

There are also types of information campaigns – as opposed to confronting campaigns – that

emphasize positive feelings and positive consequences of behaviour. Especially in men and young

people, this is often found to have better results than the use of fear appeals.

How do people react to confrontation?

If we are faced with a threat or fear, we want to reduce that threat or that fear. This puts into operation

two contradictory mechanisms, one of which prevails: a positive mechanism – we deal with the threat

or the problem by following up recommendations – or a negative mechanism – we ignore the problem

and the recommended behaviour. Information campaigns using threatening information can also

evoke emotions other than fear, for instance anger, sadness, regret, or shame. Recently there have

been doubts as to whether the specific emotion of fear is in fact necessary to cause a change in

behaviour (Carey et al., 2013; Peters et al., 2012).

There are different ways in which the problem presented by the information message can be ignored::

• denial (‘It isn’t true’)

• ridicule (‘Simply ridiculous!’)

• neutralization (‘It won’t happen to me’)

• minimization (‘All heavily exaggerated!’)

How effective is confronting information?

If the campaign message is not ignored, its effectiveness is determined by the behavioural

recommendations. The risk behaviour is most strongly reduced if the evoked emotions – both negative

and positive – are combined with feasible and effective behavioural recommendations. This has been

demonstrated by, among others, information campaigns focused on alcohol use in the traffic, smoking,

and safe sex (Witte & Allen, 2000).

A behavioural recommendation is feasible if the target group believes that it is actually applicable. ('I

can resist the temptation to drive fast on that stretch of road.’). We speak of an effective behavioural

recommendation if the target group believes that the new behaviour is feasible and really protects

against danger ('I can really reduce my risk of a crash if I drive more slowly.') (Ruiter et al., 2001;

Peters et al., 2012).

The attitude of the target group towards their own risk behaviour also determines the effectiveness of

a (confronting) information campaign. The effect is greatest if people think that their behaviour

increases their risk. But if they do not consider themselves vulnerable, the risk behaviour will not

change, despite the information about the effects of the risk behaviour and despite behavioural

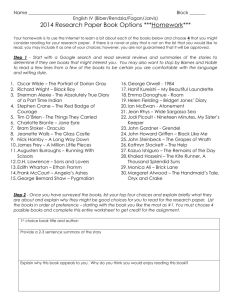

recommendations (De Hoog et al., 2005; 2008). The figure below reflects what determines the

effectiveness of an information campaign if the message is not ignored.

SWOV Fact sheet

Reproduction is only permitted with due acknowledgement

1

© SWOV, The Hague, the Netherlands

July 2015

Especially among young people, fear appeals are not more effective than information campaigns that

combine positive emotions and images with information. A comparison between both types of

information shows that the campaign message is understood equally well in both cases (Knobbout &

Van Wel, 1996; De Hoog et al., 2005).

SWOV Fact sheet

Reproduction is only permitted with due acknowledgement

2

© SWOV, The Hague, the Netherlands

July 2015

Nor do fear appeals become more effective as the evoked emotion (fear) is more violent. The

effectiveness of the campaign is determined by the feasibility and effectiveness of the behavioural

recommendation.

Campaigns that do evoke fear but at the same time contain behavioural recommendations that are

insufficiently feasible or effective, lead to adverse effects such as rejection of and resistance to the

message (Peters et al., 2012).

How effective is confronting information for traffic safe behaviour?

Evaluation studies of road safety fear appeals find both positive and negative effects. Generally these

effects only relate to changes in behaviour and behavioural intentions. It is difficult to determine

whether fear appeals indeed lead to fewer traffic crashes.

+

Research in Australia and New Zealand has shown that the use of fear appeals in the media may

have a positive effect: a reduction of unsafe traffic behaviour. The Australian research reports 5 to 7%

fewer casualties as a result of the fear appeals in the media (Cameron et al., 2003; Tay, 2002).

0

Other road safety studies reported no effect or even a negative effect as a result of fear appeals. A

meta-analysis of 13 studies, for example, found no effect.at all.

-

However, an adverse, negative effect of fear appeals is also possible. Several examples can be

found to illustrate this:

1. American students were found to be more positive about driving under the influence of alcohol

(Kohn et al., 1982) after a fear appeal and in an experiment in a driving simulator young men who

had seen a road safety fear appeal were found to drive faster than the group that had seen a

neutral film (Taubman Ben-Ari et al., 2000). This adverse effect was only found in young men who

had indicated on a questionnaire that driving was important for their self-esteem.

2. Some more recent studies also found adverse effects of fear appeals, for example about speed

behaviour (Jessop et al, 2008), about binge drinking (Jessop & Wade, 2008) and about distraction

in traffic (Lennon et al., 2010).

3. A Dutch study also found that a television fear appeal showing confronting images of a road

crash had an adverse effects (Goldenbeld et al., 2008). After having seen the fear appeal the male

participants considered speeding less hazardous, were less inclined to adhere to the speed limit,

and played down the message (“speeding is dangerous”) and the behavioural recommendation

(“do not speed, keep to the limit”).

4. Several Belgian studies indicate that fear appeals do indeed have a short-lived effect on

attitudes and opinions, but that the target group quickly gets used to the element of fear. This

would explain the effects fading out sooner than those of information using positive emotions

(Prigogine, 2004).

Checklist fear appeals

When are confronting information campaigns useful and which points must be considered if the choice

is made to use a confronting information campaign?

Only use fear appeals if a thorough pre-study shows that the resulting effects are in the desired

direction (that is, the direction that facilitates the choice for safe behaviour). Brennan & Binney

(2010), for example, found that fear appeals can evoke anger or evasion of the message,

especially when the information appeals to empathy and has a certain level of horror or shock.

Carry out a pre-study with focus groups (group interviews following the showing of informative

examples). This provides valuable insights about the clarity and attractiveness of the information.

Keep in mind, however, that people are not always capable of assessing how information

influences themselves and others. When people say that a film has made a great impression and

say that, according to them, it will work well on others, then this is not necessarily correct. Nor does

SWOV Fact sheet

Reproduction is only permitted with due acknowledgement

3

© SWOV, The Hague, the Netherlands

July 2015

a positive opinion on a film automatically mean that test-viewers are also inclined to indeed change

their own behaviour.

Determine in advance whether the feasible and effective behavioural recommendations have been

worked out optimally and whether the information increases the perception of individual

vulnerability, in case the sense of vulnerability is low (Lewis et al., 2007). There doesn't necessarily

have to use a high level of fear. It is much more important that individuals feel personally

vulnerable and that they think that can easily use a behavioural solution.

Test the effects of fear appeals in an experimental setting with a control group. It is advisable to

compare fear appeals with milder forms of information and to test for both negative and positive

effects. Carefully consider the primary target group (for example, young men) and also look at the

difference in effect between different campaign groups, for example the difference in response

between men and women.

Use a clear slogan with a behavioural recommendation (what the target group must do). Not: "If

you drink then drive, you are a bloody idiot". But: "100% BOB (sober), 0% alcohol."

Publicaties en bronnen (alfabetisch)

Brennan, L. & Binney, W. (2010). Fear, guilt, and shame appeals in social marketing. In: Journal of

Business Research, vol. 63, nr. 2, p. 140-146.

Cameron, M., Newstead, S., Diamantopoulou, K. & Oxley, P. (2003). The interaction between speed

camera enforcement and speed-related mass media publicity in Victoria. Report No. 201. Monash

University Accident Research Centre, Melbourne, Victoria.

Carey, R.N., McDermott, D.T., & Sarma, K.M. (2013). The impact of threat appeals on fear arousal

and driver behavior: A meta-analysis of experimental research 1990-2011. PLoS ONE, vol. 8, nr. 5,

e62821.

Goldenbeld, C., Twisk, D. & Houwing, S. (2008). Effects of persuasive communication and group

discussions on acceptability of anti-speeding policies for male and female drivers. In: Transportation

Research Part F; Traffic Psychology and Behaviour, vol. 11, nr. 3, p. 207-220.

Hoog, N. de, Stroebe, W. & Wit, J.B.F. de (2005). The impact of fear appeals on processing and

acceptance of action recommendations. In: Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, vol. 31, nr. 1,

p. 24-33.

SWOV Fact sheet

Reproduction is only permitted with due acknowledgement

4

© SWOV, The Hague, the Netherlands

July 2015

Hoog, N. de, Stroebe, W. & Wit, J.B.F. de (2008). The processing of fear-arousing communications:

How biased processing leads to persuasion. In: Social Influence, vol. 3, nr. 2, p. 84-113.

Jessop, D.C., Albery, I.P., Rutter, J. & Garrod, H. (2008). Understanding the impact of mortalityrelated health risk information: A terror management theory perspective. In: Personality and Social

Psychology Bulletin, vol. 34, nr. 7, p. 951-964.

Jessop, D.C. & Wade,J. (2008). Fear appeals and binge drinking: A terror management theory

perspective. In: British Journal of Health Psychology, vol. 13, nr. 4, p. 773–788.

Knobbout, J. & Wel, F. van (1996). Jongeren en angstaanjagende voorlichting. In: Tijdschrift voor

Communicatiewetenschap, vol. 24, nr. 3, p. 246-258.

Kohn, P.M., Goodstadt, M.G., Cook, G.M., Sheppard, M. & Chan, G. (1982). Ineffectiveness of threat

appeals about drinking and driving. In: Accident Analysis and Prevention, vol. 14, nr. 6, p. 457-464.

Lennon, R., Rentfro, R. & O’Leary, B. (2010). Social marketing and distracted driving behaviours

among young adults: The effectiveness of fear appeals. In: Academy of Marketing Studies Journal,

vol. 14, nr. 2, p. 95-113.

Lewis, I.M., Watson, B & Tay, R. (2007). Examining the effectiveness of physical threats in road safety

advertising: The role of the third-person effect, gender, and age. In: Transportation Research Part F;

Traffic Psychology and Behaviour, vol. 10, nr. 1, p. 48-60.

Peters, G-J.Y., Ruiter, R.A.C. & Kok, G. (2012). Threatening communication: a critical re-analysis and

a revised meta-analytic test of fear appeal theory. In: Health Psychology Review, vol. 7, supplement 1,

S8 - S31.

Prigogine, J. (2004). Vergelijking van 24 verkeersveiligheidscampagnes. In: Via Secura, vol. 62,

p. 8-10.

Ruiter, R.A.C., Abraham, C. & Kok, G. (2001). Scary warnings and rational precautions: a review of

the psychology of fear appeals. In: Psychology & Health, vol. 16, nr. 6, p. 613-630.

Taubman Ben-Ari, O., Florian, V. & Mikulincer, M. (2000). Does a threat appeal moderate reckless

driving? A terror management theory perspective. In: Accident Analysis and Prevention, vol. 32, nr. 1,

p. 1-10.

Tay, R. (2002). Exploring the effects of a road safety advertising campaign on the perceptions and

intentions of the target and nontarget audiences to drink and drive. In: Traffic Injury Prevention, vol. 3,

nr. 3, p. 195-200.

Witte, K. & Allen, M. (2000). A meta-analysis of fear appeals: Implications for effective public health

campaigns. In: Health Education & Behaviour, vol. 27, nr. 5, p. 608-632.

SWOV Fact sheet

Reproduction is only permitted with due acknowledgement

5

© SWOV, The Hague, the Netherlands

July 2015