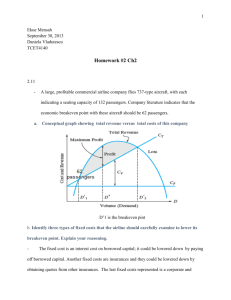

1949 BREAKEVEN ANALYSIS OF THE PROFIT-VOLUME REIATIONSHIP S.

advertisement