MOTORCYCLING AFTER 30 by Narelle Haworth

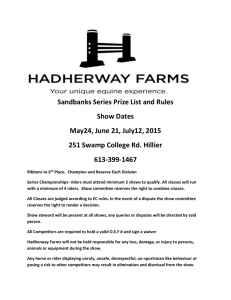

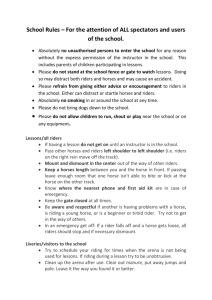

advertisement