BEEF COW SHARE LEASE ARRANGEMENTS

advertisement

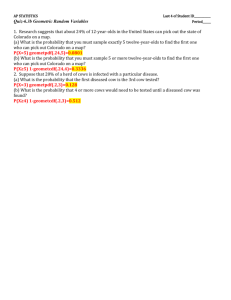

BEEF COW SHARE LEASE ARRANGEMENTS James Oltjen,1 Daniel Drake 2 and Mark Nelson 3 of the cow herd operation with the owner. Borrowing may still be required for short term operating expenses. Advantages of Leasing Arrangements 1. Allows the operator to acquire the use of resources without making a direct monetary investment in the assets. Leasing arrangements between ranch operators and cattle owners are being used more in livestock production today than ever before. Leasing has long been used to acquire control of land, but now it is being used with livestock. It is used for a number of reasons—it allows one with little capital to lease cows and, perhaps, land as well; it allows for intergenerational transfers of the cow herd. Cow leasing is not new, but there is relatively less historical precedent compared to other agricultural leases. What is fair is still a common question. This publication discusses the practice of leasing a cow herd. The owner of the cow herd is referred to as the owner and the party who leases the cow herd is referred to as the operator. 2. Allows the risk and profit associated with livestock production to be shared. 3. Can provide a more efficient use of resources (land, labor and capital). 4. Can allow the owner to spread the sale of a cow herd, and avoid potentially large capital gains. 5. Can allow the owner to convert taxable income from “selfemployment earnings” to “nonparticipation income.” Disadvantages of Leasing Arrangements Purpose of Leasing Arrangements Ranching requires control of large amounts of capital if the operator is to have adequate net income for a comfortable living. It is difficult, if not impossible, for ranch operators to acquire adequate capital without borrowing. Leasing livestock is a form of acquiring control of additional capital. However, rather than borrowing this capital from a bank or lending institution, the operator borrows from another individual or firm. The operator acquires the use of a cow herd and shares the costs and returns Ranch Business Management 1. Both owner and operator give up some individual control and income earning potential. 2. Takes more time, effort and records. 3. Could be difficult to prove that the owner is not materially participating. “Cow Herd” Versus “Cow” Leases The first step in developing a lease between two individuals is to decide whether the lease is for a cow or a cow 1996 113 herd. For the purposes of this paper, let’s define a “cow” lease as one where no one furnishes replacements. The lease, then is viewed as a single cow lease, when the cow is culled, the owner receives the income. When the entire herd is sold, the lease is over. This type of lease works well for producers who wish to get out of business, yet spread the sale of the cow herd over a period of years. It also provides for ownership transfer between generations. A “cow herd” lease is viewed as an ongoing business arrangement whereby the owner is responsible for providing replacements. The replacements may be purchased from outside the lease arrangement, or can be raised within the leased cow herd by the operator but subtracted from the owners “share.” In either case, the owner would receive all cull income. What Is a Fair Leasing Agreement? In developing a lease, owners and operators want an arrangement that is fair to both parties. As a rule, leasing arrangements are considered fair if the parties involved each receive approximately the same percent of income as the percent of costs they contribute. Bargaining may have an important influence on the value placed on contributions. Forms can be used to determine the basic contributions of both owner and operator. These are especially helpful when working out a leasing arrangement for the first time. In such cases there may be no past record of expenses involved in production. Costs To Be Considered There are two types of costs to consider when determining the amount that each party contributes towards an operation. These are fixed and variable costs. Fixed costs are incurred due to owning property, and are often referred to as ownership costs. Usually these costs are called the DIRTI five - depreciation, interest, repairs, taxes, and insurance. It is assumed that these costs are incurred regardless of operating levels and returns. Variable costs are incurred in day-today operations. In a livestock operation, variable costs include feed, labor, veterinary, drugs, trucking, and marketing, as well as miscellaneous costs. These costs are sometimes called operating costs. In most leasing agreements, the owner is responsible for fixed costs of the livestock and perhaps for some variable costs. The operator is generally responsible for most of the variable costs, and may also furnish some fixed costs. In a cash lease, the operator may pay the owner cash rent equal to the owner’s fixed costs. Other Factors To Consider Other factors besides fixed and variable costs also need to be considered when preparing a livestock leasing agreement. In the case of a cow herd, some other factors include: 1. Who provides/pays the breeding bill? 2. Contingencies (e.g. drought, death loss): how will they be handled? It is best if an owner and operator can work together in determining their respective contributions. They might work independently at first; then they will be better prepared to resolve any differences. Ranch Business Management 3. Who makes which management decisions (e.g. culling, sale time)? 1996 114 4. The lease itself: length, renewability, termination? 5. How is income divided? 6. How will price be set if one party purchases the other’s share? Determining Sharing Arrangements Three things need to be determined for an equitable leasing arrangement. These need to be done by the operator and owner working together: each party may be set based on historical costs. In such cases, validation of the proportions with current records is important. Consider these estimates (Example 1) valid only under the costs, production level, and prices specified. Individuals or groups using the information provided should substitute costs, production levels, and prices valid for the locality, management level to be adopted, and marketing circumstances for the location and time period involved. Variable Expenses 1. Determine the costs to be considered. 2. Determine the contributions of each party. Feed 1. Pasture is a feed cost. If the pasture is owned by the party providing it, the pasture cost could be a reasonable rate of return (2 to 6 percent) based on its value, or it could be the amount for which it could be rented to someone else. If the pasture is rented by the party providing it, then his contribution is the actual cash rent. 2. Supplemental pasture in the form of crop or pasture residue or other grazing is a contribution towards feed costs and credit should be given to the party who provides this feed. 3 & 4. Hays are considered as feed costs and should be valued at market prices. 5. If grain is used in the operation, value at market price. 6. Protein, mineral, and vitamins are valued at market price. These items should be furnished by the same party 3. Determine the percent of costs contributed by each party. When these three factors are determined, the operator and owner should share in income in the same proportion as they contribute to the operation. Evaluate the leasing agreement occasionally to assure an equitable arrangement over time. Fluctuating prices and management changes can cause the proportion of the contributions to shift over time. Costs for a Cow Herd A worksheet (Table 1) can be used to estimate the various costs involved in the operation of a cow herd. The amount each party contributes can be credited to the party making the contribution. A short explanation of each cost item may help in arriving at an equitable figure. When historical costs are well documented, proposed new contributions by Ranch Business Management 1996 115 who provides hay and forage so there will be no conflict concerning rations. Other Expenses 7 - 11. Other expenses should include the costs of the cow herd. For example, the cost of operating capital for the operator may be a significant expense. Sources of information include tax returns and detailed financial analysis (e.g. SPA, FINPACK). 12. Labor is a contribution of the party who provides it. If labor is hired, its cost is the actual cost to the party who pays for it. If labor is furnished by one or both parties, then labor should be valued at the current cost of labor as though it had to be hired. Labor required per cow per year will vary with the size of the herd. For herds of less than 30 cows, 10 to 15 hours per cow per year may be required. Large herds will require 5 to 6 hours per cow per year. Use actual costs, if available. 13. Fixed Expenses Cows and Bulls 14. Interest on cows as an investment contribution of the owner. The interest rate used should be the approximate interest rate that could be earned if money were invested in other alternatives. If interest rates are 5 percent and the average value of a cow is $600, then the annual contribution of the owner is 5 percent of $600 for 12 months or $30. Cow value for one-year leases is her market value minus capital gains taxes; for longer term leases it is balance sheet value (a conservative base value or cost less depreciation). 15. Depreciation on cows is a contribution of the owner because he is responsible for providing replacements. It is the difference between the value of the cow when she is placed in the herd and her salvage value when she is removed from the herd. To arrive at annual depreciation, divide this figure by the number of years the cow is expected to remain in the herd. If a cow going into the herd is valued at $600 and you expect her to be worth $350 when she is removed from the herd in 7 years, then annual depreciation is $600 minus $350 divided by 7 or $35.71 per cow. Depreciation is also a contribution of the owner in the typical “cow” lease arrangement, because the cow is usually worth more at the beginning of the lease than she will be when culled. Management of a cow herd should be the responsibility of both parties. The owner of the cow should decide which cows to cull and the operator should be responsible for the day-to-day decisions involved in managing the cow herd to produce optimum returns. Placing a dollar figure on the value of good management is difficult, but no other factor is more critical when determining overall cow herd profit. Helpful guides include 5 to 8 percent of gross income or 1 to 2 percent of total capital managed. Ranch Business Management 1996 116 16. 17. Death loss of cows should be considered a contribution of the owner. Death loss is usually computed at 1 to 2 percent of the value of the breeding herd. There should be contingencies written in the lease for cases where actual death losses are greater than the percent used in the lease worksheet. 18 & 19. Annual interest and depreciation on bulls are determined the same as for cows (items 14 & 15) except bull value is estimated by dividing bull cost by the number of cows serviced. This determines the amount to charge against each cow. Buildings and Equipment 20 & 21. Interest and depreciation on buildings and equipment used in the operation is a contribution of the party who owns the buildings and equipment. Again, figure the interest on the value of the buildings and equipment according to an interest rate that approximates investment returns. Depreciation is the decrease in the value of the property in a year’s time. 22. the current value of buildings and .5 to 1 percent of the current value of livestock equipment. Insurance on livestock will usually be about .1 to .25 percent of the value of the breeding herd. Bull value is estimated by dividing its cost by the number of cows serviced, e.g. $2,500 ÷ 25 cows/bull = $100. Taxes and insurance on buildings and equipment is the cost for taxes and insurance incurred against property used for livestock during the year. This will amount to 1 to 1.5 percent of Ranch Business Management Determining Contribution of Each Party After it has been determined which costs each party contributes, list these amounts in the appropriate column on the worksheet. The totals of the owner and operator columns will show the total contribution of costs for each party. These totals might make both parties concerned as to the profitability of the cow herd operation. This is the risk that each party assumes. If returns per cow exceed the value of all contributions, then each party will get full value of all contributions. If contributions are greater than the returns, then each party will not receive full value of his contributions. However, this does not mean that each party does not benefit from the operation. There are benefits such as capital gain advantages, way of life, and pride of ownership realized by the owner. There may also be advantages in the use of otherwise unsalable feed and in the use of offseason labor for the operator. Determining Percent Contributed by Each Party As illustrated in Example 1, a simple way to calculate the percent contributed by each party is to separate the total contributions into the amount contributed by each party and then divide by the total contribution. In Example 1, the owner receives 22.07% of the calf crop and all of the cull income from sale of cows (7 year life, 100 cows ÷ 7 years = 14.29 cows/ year) and bulls (6 year life, 100 cows ÷ 1996 117 25 cows/bull = 4 bulls, 4 bulls ÷ 6 years = .6667 bulls/year). If 100 cows had been exposed to a bull and a 85% calf crop was weaned, the owner would receive: 85 calves (550 lb. @ $.90/lb.) x .2207 14.29 cull cows (@ $350) .6667 cull bulls (@700) 9,285 5,000 467 $14,752 In addition it is important to note, the owner would be responsible for replacing the 14.29 culled cows, the 1 dead cow (100 cows @ 1% death loss), the .6667 culled bulls, and the .04 dead bulls (4 bulls @ 1% death loss). The operator would receive 77.93% of the calf crop: 85 calves (550 lb. @ $.90/lb.) x .7793 $32,790 Profit or Loss? In this example, the operator’s costs are $31,930 ($319.30 x 100 cows), resulting in a profit of $860 ($32,790 $31,930). The owner’s calculated costs from Example 1 are $9,041 ($90.41 x 100 cows), but his total estimated expenses include replacing the cull animals since he is providing the cow herd. These expenses are $14,508 which include replacing the salvage value of what was sold ($5,467). His out of pocket expenses are: 15.29 replacement cows @ $600 .7067 bulls @ $2,500 Total other costs of $35.70 X 100 cows 9,171 1,767 3,570 $14,508 The $35.70 per cow cost is $30 interest on cows + $5 interest on bulls + $.70 insurance. The owner’s net result is a profit of $244 ($14,752 - $14,508). Another way to consider or check profit Ranch Business Management is to exclude cull and death income and expenses. Then the owner would have an income of $9,285 and expense of $9,041 for a net gain of $244. Thus, each party receives the same proportion of net returns as they contribute in costs. Total returns are $42,075 (85 calves x 550 lb @ $.90/lb); total costs are $40,971 ($409.71/cow x 100 cows). Total net returns are thus $1,104 ($42,075 - $40,971). The operator nets $860, or 77.93% of $1,104; the owner nets $244, or 22.07% of $1,104. Accounting Procedures for Raising Replacements Within the Cow Herd When the owner is furnishing replacements to replenish the cow herd, and they are selected and raised from the calf crop, the value and cost to raise these replacements must be subtracted from the owner’s share. In Example 1, the owner’s share of income could be amended to include the value of the replacements: Income 85 calves (550 lb. @ $.90/lb.) x .2207 14.29 cull cows (@ $350) .6667 cull bulls (@700) Costs 15.29 replacement heifers (550 lb. @ $.90/lb.) Growing phase cost estimate, pay to operator .7067 bulls @ $2,500 Total other costs of $35.70 X 100 cows Amended Income 9,285 5,000 467 $14,752 7,566 2,136 1,767 3,570 $15,039 (-$287) The costs to grow the replacement heifers from weaning age to 15 months for breeding is estimated by using a monthly charge (based on the annual cost per cow adjusted to 3/4 of an 1996 118 animal unit) times the number of months from weaning to breeding age (3/4 X 15.29 females X $319.30 annual cost / 12 months X 7 months). In the example, heifers are weaned at 8 months of age and grown for 7 months before reaching breeding age at 15 months. Specific growing period costs should be used when available. If additional replacements are saved for later culling, their costs and cull income would be assigned to the owner. In the above example, from a strictly out-of-pocket cash basis, raising replacements is clearly less profitable compared to purchase of breeding age females. The additional cost is $1,136 ($7,566 + $2,741 - $9,171). However, long-term genetic gains, improved animal health, and pride of ownership are possible offsetting benefits, which may also improve income from future calf and cull sales. In the event the owner purchases replacements of under-breeding age, growing costs from purchase until attainment of breeding age should be assigned as in the example above. Conclusions The methods described in this publication are not the only ones available, but these are accepted as fair for the assumptions stated. Other lease options available include cash leases, fixed percent of calf crop, and lease with the option to buy. In all cases, records are important to both establish a lease, as well as to evaluate it through time. Current estimates and projections are needed to adjust the lease as described above, and historical analyses allow one to factor risk and temper any changes. Communication and negotiation between the two parties is important for keeping this form of lease equitable. For Further Reading Bennett, Myron. 1979. Livestock-Share Rental Arrangements for Your Farm. North Central Regional Publication 107. Erickson, Lorne, Merle Good, and Bill Heidecker. Negotiating Cow Lease Arrangements. Farm Business Management Branch, Alberta Agriculture. Feuz, Dillon, Norman L. Dalsted, and Paul H. Gutierrez. 1990. Leasing Cows — What is Equitable. Journal of the American Society of Farm Managers and Rural Appraisers 54:21-28. Robb, James G., Daryl E. Ellis, and Steven T. Nighswonger. 1989. Share Arrangements for Cowcalf or Cow-yearling Operation: COWSHARE a Spreadsheet Program. Nebraska Cooperative Extension, CP-2. University of Nebraska, Lincoln. Livestock Specialist1 Animal Science Dept. University of California, Davis Livestock Advisor2 Siskiyou County Cooperative Extension University of California Livestock Specialist3 Cooperative Extension Service Kansas State University Ranch Business Management 1996 119 Example 1. Beef “Cow” Lease or “Cow Herd” Lease with replacements purchased outside the arrangement ($/cow). Total Contribution Variable Expenses FEED: 1. Pasture 2. Crop residue pasture 3. Hay: ________________ 4. Hay: ________________ 5. Grain 6. Protein, minerals and vitamins OTHER EXPENSES: 7. Veterinary and drugs 8. Fuel, oil and utilities 9. Repairs and supplies 10. Marketing and trucking 11. Miscellaneous: operating capital 12. Labor 7 hrs @ $6.00 /hour 13. Management 475.42 gross income/cow @ 5 % Fixed Expenses COWS AND BULLS: 14. Interest on cows 600 @ 5 % 15. Depreciation on cows ( 600 - 350 ) / 7 years 16. Insurance on herd ( 600 + 100 ) @ .1 % 17. Death loss ( 600 + 100 ) @ 1 % 18. Interest on bulls 100 @ 5 % 19. Depreciation on bulls ( 2,500 - 700 )/ 6 years/ 25 cows Operator’s Share $ / cow 82 16 90 82 16 90 5 5 $ / cow 7 11 9 6 4 42 7 11 9 6 4 42 23.77 23.77 $ / cow 30 30 35.71 35.71 .70 .70 7 5 7 5 12 12 BUILDINGS AND EQUIPMENT: 20. Interest on buildings and equipment value 230 /cow @ 5 % 21. Depreciation on bldgs. and equip. ($/cow) 22. Taxes & insurance, bldgs. and equip. 120 @ 1.25 % + 70 @ 0.75 % 11.5 10 TOTAL CONTRIBUTIONS (sum of lines 1-22) 409.71 $ / cow 11.5 10 2.03 PERCENT OF TOTAL CONTRIBUTIONS Ranch Business Management Owner’s Share 1996 2.03 90.41 319.30 22.07 % 78.93 % 120 Table 1. Fill in values in the worksheet to evaluate possible arrangements ($/cow). Total Contribution Variable Expenses FEED: 1. Pasture 2. Crop residue pasture 3. Hay: ________________ 4. Hay: ________________ 5. Grain 6. Protein, minerals and vitamins Owner’s Share Operator’s Share $ / cow OTHER EXPENSES: 7. Veterinary and drugs 8. Fuel, oil and utilities 9. Repairs and supplies 10. Marketing and trucking 11. Miscellaneous: operating capital 12. Labor hrs @ $ /hour 13. Management gross income/cow @ % Fixed Expenses COWS AND BULLS: 14. Interest on cows @ % 15. Depreciation on cows ( )/ years 16. Insurance on herd ( + )@ % 17. Death loss ( + )@ % 18. Interest on bulls @ % 19. Depreciation on bulls ( )/ years/ cows BUILDINGS AND EQUIPMENT: 20. Interest on buildings and equipment value /cow @ % 21. Depreciation on bldgs. and equip. ($/cow) 22. Taxes & insurance, bldgs. and equip. @ %+ @ % $ / cow $ / cow $ / cow TOTAL CONTRIBUTIONS (sum of lines 1-22) PERCENT OF TOTAL CONTRIBUTIONS Ranch Business Management 1996 % 121 % FROM: California Ranchers' Management Guide Steven Blank and James Oltjen, Editors. California Cooperative Extension Disclaimer Commercial companies are mentioned in this publication solely for the purpose of providing specific information. Mention of a company does not constitute a guarantee or warranty of its products or an endorsement over products of other companies not mentioned. The University of California Cooperative Extension in compliance with the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972, and the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 does not discriminate on the basis of race, creed, religion, color, national origins, or mental or physical handicaps in any of its programs or activities, or wish respect to any of its employment practices or procedures. The University of California does not discriminate on the basis of age, ancestry, sexual orientation, marital status, citizenship, medical condition (as defined in section 12926 of the California Government Code) or because the individuals are disabled or Vietnam era veterans. Inquires regarding this policy may be directed to the Personnel Studies and Affirmative Action Manager, Agriculture and Natural Resources, 2120 University Avenue, University of California, Berkeley, California 94720, (510) 644-4270. University of California and the United States Department of Agriculture cooperating. Ranch Business Management 1996 122