Document 10658188

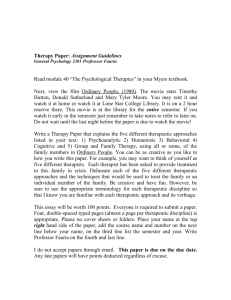

advertisement