Survival and Recruitment in a Human-Impacted Population of Ornate Box Turtles,

advertisement

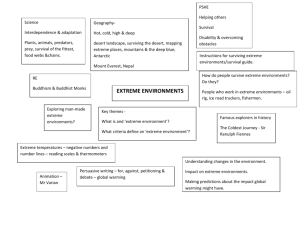

Journal of Herpetology, Vol. 38, No. 4, pp. 562–568, 2004 Copyright 2004 Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles Survival and Recruitment in a Human-Impacted Population of Ornate Box Turtles, Terrapene ornata, with Recommendations for Conservation and Management KENNETH D. BOWEN,1 PAUL L. COLBERT, AND FREDRIC J. JANZEN Department of Ecology, Evolution, and Organismal Biology, 339 Science II, Iowa State University, Ames, Iowa 50011 USA ABSTRACT.—Alteration and loss of habitat is a major factor in the recent declines of many turtle populations. However, there are few studies of turtle populations in areas that are used intensively by humans. We used temporal symmetry modeling and an information-theoretic approach to model selection to estimate survival and recruitment in a population of Ornate Box Turtles, Terrapene ornata, in fragmented, isolated habitat over an eight-year period. Apparent annual survival was high during this period (0.97, SE 5 0.06), as was the seniority probability (0.95 6 0.04). Recruitment into the adult population (k) was estimated at 1.02 (6 0.06). Our results suggest a healthy population, but we note several reasons for a cautious management approach. These include a vulnerability of k to the removal of adults, the need for increased recruitment to offset loss of genetic diversity, and the uncertainty of our estimates resulting from the sampling and modeling processes. Habitat loss and fragmentation increase risk of extirpation for populations of a variety of taxa (Burkey, 1995; Fahrig, 2002; Hokit and Branch, 2003a). Once a patch of habitat becomes small and isolated, stochastic and deterministic factors can lead to a decline in the vital rates of populations inhabiting that patch (Lande, 1993; Hokit and Branch, 2003a,b). Even when populations persist, severe declines in vital rates can result in bottlenecks and a loss of genetic diversity (Hoelzel, 1999; Kuo and Janzen, 2004). From a conservation and management perspective, it is, therefore, crucial to assess the demographic and genetic health of populations in areas where human activity has reduced the amount of available habitat. Habitat alteration is implicated as a critical factor in the widespread decline of turtle populations (Mitchell and Klemens, 2000), but there are few attempts to rigorously estimate parameters of turtle populations in areas that are used intensively by humans (Doroff and Keith, 1990; Kazmaier et al., 2001). Studies of this kind are needed to guide management decisions given current rates of habitat destruction and the conservation status of many turtle species. Furthermore, there are few studies that use data from multiple sources (i.e., population ecology and molecular genetics) to gauge the health of turtle populations in degraded areas (Rubin et al., 2001, 2004). Assessing demographic health of turtle populations begins with estimating adult survival 1 edu Corresponding Author. E-mail: kbowen@iastate. and recruitment into adult populations. Growth rate of turtle populations is most sensitive to adult survival (Heppell, 1998), and loss of adults can lead to population declines regardless of reproductive rates (Congdon et al., 1993, 1994; Heppell et al., 1996). Although many studies of turtle demography use mark-recapture models to estimate population parameters, few authors consider the assumptions of these models (Lindeman, 1990), and variance (uncertainty) of population estimates is rarely reported (Langtimm et al., 1996). Furthermore, models such as the Cormack-Jolly-Seber (CJS) model for open population survival estimates (Cormack, 1964; Jolly, 1965; Seber, 1965) and information-theoretic approaches to model selection such as Akaike’s Information Criterion (AIC; Akaike, 1973) are used infrequently in studies of turtle demography (but see Kazmaier et al., 2001; Fonnesbeck and Dodd, 2003). These methods are useful because they allow researchers to construct models of population processes and estimate population parameters based on knowledge of the study organism and study methods. In turn, researchers can determine what models are most appropriate for the data, retain the ‘‘best’’ model or models, and calculate reliable estimates of uncertainty for parameter estimates (Anderson et al., 2000; Burnham and Anderson, 2002; Fonnesbeck and Dodd, 2003). In this study, we used a CJS framework and AIC to estimate annual adult survivorship and recruitment in a fragmented and isolated population of Ornate Box Turtles (Terrapene ornata) on the periphery of the species’ geographic range. DEMOGRAPHY AND CONSERVATION OF TERRAPENE ORNATA MATERIALS AND METHODS Study Area and Field Methods.—Surveys were conducted on a portion of the Upper Mississippi River National Fish and Wildlife Refuge in Carroll and Whiteside Counties, Illinois. The study site consists of approximately 2750 m of shoreline that extends along a slough on the eastern bank of the Mississippi River and spans approximately 75–175 m inland from the slough to a bike path and/or boundary fence. The area is primarily sand-prairie dominated by needlegrass (Stipa sp.) with interspersed patches of prickly pear cactus (Opuntia humifusa), skunkbrush (Rhus aromatica), and Ohio spiderwort (Tradescantia ohiensis). Trees are continuous along the shoreline of the slough and are scattered throughout the disturbed southern portion of the area where several houses are located. The site is fragmented into three major sections of sand prairie by roads, bike paths, fences, and houses. We treat the three sections as one site in demographic analyses because we have observed turtles moving among all of them. Much of the adjoining land is tilled, in cultivation, or is otherwise unsuitable habitat for T. ornata (see Kolbe and Janzen, 2002 for further description of the study area). We hand-captured turtles through systematic searches of the study site. Investigators performed surveys in the same manner upon each visit, walking on parallel transects through the habitat while scanning for turtles. Searches were conducted periodically from late-May to earlyJuly during cooler morning periods when turtles were most active (Legler, 1960; Converse and Savidge, 2003; Plummer, 2003). Capture effort varied substantially among years and could be grouped into four categories based on person hours spent searching. In 1997, 340 h were spent searching; in 1996, 287 h, in 1998–1999 from 207– 247 h, and in 2000–2003 search effort ranged from 30–52 person hours in each year. Upon capture, previously uncaptured turtles were individually marked by notching the marginal scutes with a triangular file (Cagle, 1939). Turtles were classified as adults or juveniles based on the presence/absence of secondary sex characteristics (Legler, 1960). Sex of adults was determined according to criteria used by Legler (1960). Demographic Analysis.—The CJS model uses two parameters to model captures and recaptures for open populations: capture probability (pi ; where i denotes a given time period) describes the probability that an animal will be captured at sampling period i; apparent survival (/i) is the probability that a marked animal survives and remains in the population until time i þ 1. We used the temporal symmetry approach of Pradel (1996) available in Program MARK 563 (White and Burnham, 1999) to estimate pi and /i. This method is similar to CJS modeling but allows inference about recruitment through estimation of an additional seniority parameter (ci). This new parameter is estimated by considering the capture-history data in reverse time order, conditioning on the final capture of an animal and observing its captures in earlier samples (Williams et al., 2002). Therefore, ci is the probability that an animal present just before sampling period i was already present just after sampling period i 1 (i.e., that an animal is a survivor of period i rather than a new recruit). The population growth rate can then be estimated as follows (Williams et al., 2002): ki 5 /i/ciþ1. MARK performs this calculation along with the associated estimates of uncertainty. The four CJS model assumptions that must be met to reduce bias in parameter estimates are that (1) every animal in the population at the time of the ith sample has the same capture probability (pi); (2) every marked animal in the population immediately after the ith sample survives to the (i þ 1)th sample with equal probability (/i); (3) marks are neither lost nor overlooked; and (4) all samples are instantaneous and releases occur immediately following the sample (Pollock et al., 1990). These assumptions hold for reverse-time modeling as well, but assumption (2) extends to the seniority parameter as follows: every marked animal in the population just before the ith sample was present in the (i 1)th sample with equal probability (ci) (Williams et al., 2002). There is a risk of violating assumptions (1) and (2) whenever capture histories from different populations or from different segments of the same population (e.g., across age classes or sexes), are pooled (Pollock et al., 1990; Lebreton et al., 1992). Heterogeneity in / and p is thought to exist between juvenile and adult Terrapene (Legler, 1960; Iverson, 1991), but no known studies have had sufficient juvenile captures to test this assumption. This study also had insufficient juvenile captures to allow separate parameter estimation; thus, juveniles were excluded to eliminate age-based heterogeneity in / and p. We tested for sex-based heterogeneity in /, p, and c by comparing models that either pooled or grouped sexes (see below). The potential for violation of assumption (3) is greatest when less permanent marks are used (paint marks, tags, etc.), small or obscure marks are applied, or capture methodology does not allow close examination of individuals. This source of bias is unlikely in this study because of the marking and capture methodologies employed. Assumption (4) is violated by degrees in most field studies. Few samples are truly instantaneous, but it is best if sampling takes place in a period of negligible length relative to 564 K. D. BOWEN ET AL. the interval over which survival is estimated (Lebreton et al., 1992). Even more important is that the probability of mortality is low over the sampling interval (Williams et al., 2002). In our study design, we captured turtles in June of each year to estimate annual survival and seniority. Although this ratio of sampling period to survival period (month to year) is substantial, T. ornata survival rates are generally high (Doroff and Keith, 1990; S. J. Converse and J. B. Iverson, unpubl. data), and the bias induced should be minimal. Model notation in the following sections is as follows: group-specific parameters are denoted (g), time-specific parameters (t), and a single, constant parameter (.). Interactions between effects are denoted by an asterisk, for example, /(g*t) indicates an interaction between group and time on survival. Modeling of capture histories followed the procedure recommended by Lebreton et al. (1992). First, a global model allowing time and group-specific (in our case sex was the group) variation in /, p, and c was constructed. We then performed a goodness-offit test in Program RELEASE to generate an estimate of overdispersion of the data (^c) (Burnham et al., 1987). Overdispersion (extra binomial variation) signifies that heterogeneity exists among individuals, a violation of assumptions (1) and (2) that results in underestimation of sampling variances and covariances (Williams et al., 2002). TEST 2 and TEST 3 in RELEASE yielded a combined v2 of 9.31 (df 5 22, P 5 0.992), indicating that overdispersion was not an issue (^c 5 0.42). We proceeded by applying constraints to /, p, and c (i.e., removing time effects, sex effects, or both) and comparing these reduced models to their more complicated counterparts to identify the most parsimonious model (the model with the fewest parameters that best fit the data). Sex effects were assessed by comparing models allowing sex-specific /, p, and c parameters to models constraining /, p, and c to be equal across sexes. To determine the relative importance of time variation in /, p, and c, we compared models that held these parameters constant across years to those allowing separate parameters for each year. Because p was expected to vary largely with sampling effort, and sampling effort was somewhat categorical, we also constructed models that captured the nature of this variation with as few parameters as possible (p(effort) and p(g*effort) models). We did so by allowing four parameters for p corresponding to our four categories of search effort; capture probability p1 corresponds to the year 1996, p2 corresponds to the year 1997, p3 corresponds to years 1998 and 1999, and p4 corresponds to years 2000–2003. All effort-based p models out-competed their year- specific and constant-p counterparts, suggesting that search effort was most responsible for variation in p. Therefore, a reduced set of 32 p(effort) and p(g*effort) models (allowing all combinations of group and time variation in / and c) was considered for model selection. The most appropriate model from the list of candidates was chosen using an informationtheoretic criterion. This method compares competing models through optimization of the likelihood function and addition of a penalty for the number of parameters used, thereby selecting for an optimal tradeoff between bias and precision (Burnham and Anderson, 2002). In essence, this method allows the researcher to choose the model that gives the best fit to the data with the fewest parameters. Parameter estimates (/, c, p) from the chosen model are then used to describe the population. The information-theoretic approach employed by MARK, AICc, also takes into account small sample sizes in assessing model fit (Hurvich and Tsai, 1989), which is a common phenomenon in capture-recapture studies (Williams et al., 2002). To determine the most likely model in our set of candidates, AICc values were compared (lowest being best) as were the Akaike weights (highest being best) given each model with respect to others in the set. For parameter estimates near 1.0 (/ and c), we calculated Profile 95% Confidence Intervals that use a chi-square distribution (an option in MARK) rather than a normal distribution (Williams et al., 2002). RESULTS Eight years of surveys resulted in 136 total captures of 84 individuals. Of those captured, 30 (35.7%) were males, 43 (51.2%) were females, nine (10.7%) were juveniles, and two (2.4%) were adults of unknown sex (excluded from analysis). In adults of known sex, the ratio of males to females was 0.7, and the ratio of juveniles to all adults was 0.12. Model selection allocated the most support (99%; Table 1) to models with p(effort) rather than p(g*effort), indicating that capture probability is equal across sexes and varies with search effort. Many models received no support. We present only those models that received an Akaike weight of at least 0.01 (Table 1). A pattern existed among p(effort) models in which those with constant seniority performed best (combined Akaike weight 5 0.67) followed closely by models with sex-specific seniority (combined Akaike weight 5 0.25) and then time-specific seniority (combined Akaike weight 5 0.07; Table 1). This provides some evidence for sex-specific seniority, although parsimony (fewer parameters) seemed more important for model fit DEMOGRAPHY AND CONSERVATION OF TERRAPENE ORNATA 565 TABLE 1. Alternative models for estimation of survival (/), recapture (p), and seniority (c) parameters from Pradel temporal symmetry modeling for adult Terrapene ornata in Carroll and Whiteside Counties, Illinois, 1996– 2003. For each model, (t) indicates that parameters are time (year) specific, (g) indicates parameters are group (sex) specific, (.) indicates that parameters are constant over time, (effort) indicates classification based on sampling effort, and (*) indicates an interaction. The most parsimonious model is generally considered the best for describing the data, and is identified as the model with the lowest AICc score and the highest weight (see text for more detail). Model AICc Delta AICc Weight Number of parameters Deviance /(.)p(effort)c(.) /(g)p(effort)c(.) /(.)p(effort)c(g) /(g)p(effort)c(g) /(.)p(effort)c(t) /(g)p(effort)c(t) /(.)p(g*effort)c(.) /(g*t)p(g*effort)c(g*t) 723.34 723.84 725.24 726.01 727.67 728.33 730.30 783.72 0.00 0.50 1.90 2.67 4.33 4.99 6.96 60.38 0.38 0.29 0.15 0.10 0.04 0.03 0.01 0 6 7 7 8 11 12 10 36 444.18 442.50 443.90 442.46 437.33 435.66 442.25 430.92 (Burnham and Anderson, 2002). Within this framework, constant survival models out-competed sex-specific counterparts, again showing the importance of parameter reduction for model fit. As before, the proximity of competing constant and sex-specific survival models makes it difficult to rule out gender effects on survival. Although model /(.)p(effort)c(.) garnered the most support (38%; Table 1), the proximity of model /(g)p(effort)c(.)( AIC 5 0.5; Table 1) makes it impossible to choose between the two (Burnham and Anderson, 2002). Therefore, sex potentially affected survival, but reducing the number of parameters required to model capture histories provided a better fit. TABLE 2. Estimates of survival (/), recapture (p), and seniority (c) parameters from model /(g)p(effort)c(.) from Pradel temporal symmetry modeling for adult Terrapene ornata in Carroll and Whiteside Counties, Illinois, 1996–2003. Estimates of uncertainty and upper and lower 95% confidence intervals are shown for each. Recapture probability p1 corresponds to 1996, p2 corresponds to 1997, p3 corresponds to years 1998 and 1999, and p4 corresponds to years 2000–2003. The 95% CIs for / and c were calculated based on a chi-square distribution, whereas those for estimates of p were calculated based on a normal distribution (see text for more detail). Parameter Estimate SE Coefficient of variation / (male) / (female) p1 p2 p3 p4 c 0.90 0.99 0.16 0.36 0.28 0.08 0.95 0.08 0.06 0.04 0.07 0.05 0.03 0.04 0.09 0.06 0.25 0.19 0.18 0.38 0.04 Lower 95% CI Upper 95% CI 0.75 0.87 0.09 0.24 0.19 0.05 0.86 1.00 1.00 0.26 0.49 0.38 0.15 1.00 With such a competitive group of candidate models, averaging of parameter estimates across models would normally be warranted (Burnham and Anderson, 2002). However, this approach is not feasible with our model set because of the variable parameterizations of the top models (for example, it is illogical to average survival parameters from models with and without group effects on survival). We chose to interpret data based solely on the ‘‘best’’ model (/(.)p(effort)c(.)) for three reasons: (1) the lack of a logical method for averaging among our top models; (2) the relative superiority of models with constant survival and constant seniority (Table 1); and (3) the fact that it was the most parsimonious of the top models. However, parameter estimates for model /(g)p(effort)c(.) are also reported (Table 2) because we cannot rule out the possibility of sexspecific survival. The estimate of survival from model /(.)p(effort)c(.) was high (0.97, SE 5 0.06; Table 3), as was the estimate for seniority (0.95, SE 5 0.04; Table 3). The resulting estimate of recruitment into the adult population (k) was 1.02 (SE 5 0.06), suggesting a stable population. Because we did not model average, our estimates of variance are likely to be underestimates (Burnham and Anderson, 2002). DISCUSSION Our estimate of survival is comparable to those found in other demographic studies of box turtles. Using the Jolly-Seber method, Schwartz et al. (1984) estimated an annual survival of 0.819 for all individuals in a population of Terrapene carolina triunguis, and Doroff and Keith (1990) estimated annual survival of adult female T. ornata at 0.816 (95% CI 0.69–0.94) and survival of adult males as 0.813 (0.70–0.93) in a degraded area. S. J. Converse and J. B. Iverson (unpubl. data) estimated an annual survival of 0.932 (SE 5 0.014) and 0.882 (SE 5 0.022) for female and male 566 K. D. BOWEN ET AL. T. ornata, respectively, in an undisturbed area. Our estimate of mean survival for all marked adults (0.97) is higher than these estimates. However, the 95% CI of our estimate (0.85–1.0) suggests that the populations may be more similar than indicated by a simple comparison of mean survival. Langtimm et al. (1996) estimated weekly survival rates of 0.937–1.0 in a population of Terrapene carolina bauri. These estimates would appear to be similar to ours, but the lowest weekly survival rate extrapolated to an annual survival rate (0.93752) is equal to 0.034. We estimated annual recruitment into the adult population at 1.02 (SE 5 0.06). Kazmaier et al. (2001) estimated population growth rate at 0.981 (SE 5 0.019) for a population of Gopherus berlandieri, and S. J. Converse and J. B. Iverson (unpubl. data) estimated an annual recruitment into the adult population of 1.006 (SE 5 0.065) for an undisturbed T. ornata population. Thus, reported growth/recruitment rates from other populations of terrestrial turtles are similar to ours. Estimates of seniority can provide insight into the effects of changes in survival and recruitment on population growth rate (Nichols et al., 2000; Williams et al., 2002). At a c of 0.5, for example, survival and recruitment are equal contributors to population growth. As c increases past 0.5, survival is of increasing importance to population growth rate (with recruitment decreasing in importance; Williams et al., 2002). Our estimated seniority probability of 0.95 (SE 5 0.04) over the eight years of the study suggests that a change in survival will have a much greater effect on population growth rate than will a proportional change in recruitment into the adult population. The importance of adult survival to population growth rate found here is consistent with results from other turtle populations (Heppell, 1998). The female-biased sex ratio of our population may be the norm for T. ornata. The relatively small number of captured juveniles also appears to be typical. Legler (1960) reported a sex ratio of 61 males to 103 females (30 juveniles) in a Kansas population. Doroff and Keith (1990) found 39 males and 62 females in their Wisconsin population, Converse et al. (2002) found 41 males, 80 females, and 23 juveniles in a Nebraska population, and Blair (1976) reported that the sex ratio was biased toward females in a Texas population. S. J. Converse and J. B. Iverson (unpubl. data) found that female survival was higher than male survival in a Nebraska population of T. ornata. If this finding were common to all populations, a sex-based difference in survival could explain the consistent bias in adult sex ratios. However, this hypothesis is inconsistent with the results of Doroff and Keith (1990) and this study. It is possible that differences in capture probability TABLE 3. Estimates of survival (/), recapture (p), and seniority (c) parameters from model /(.)p(effort)c(.) from Pradel temporal symmetry modeling for adult Terrapene ornata in Carroll and Whiteside Counties, Illinois, 1996–2003. Estimates of uncertainty and upper and lower 95% confidence intervals are shown for each. Recapture probability p1 corresponds to 1996, p2 corresponds to 1997, p3 corresponds to years 1998 and 1999, and p4 corresponds to years 2000–2003. The 95% CIs for / and c were calculated based on a chi-square distribution, whereas those for estimates of p were calculated based on a normal distribution (see text for more detail). Parameter Estimate SE Coefficient of variation Lower 95% CI Upper 95% CI / p1 p2 p3 p4 c 0.97 0.16 0.36 0.28 0.08 0.95 0.06 0.04 0.07 0.05 0.03 0.04 0.06 0.25 0.19 0.18 0.38 0.04 0.85 0.09 0.24 0.19 0.05 0.86 1.00 0.26 0.49 0.38 0.15 1.00 are responsible for the small number of observed juveniles. Legler (1960) suggested that juvenile T. ornata were much more numerous than indicated by the number captured. Kuo and Janzen (2004) reported on the genetic diversity of the same population of T. ornata that we studied. They found that the level of genetic diversity was similar to a larger reference population in Nebraska, despite a bottleneck in the recent past. Although genetic diversity is currently high, they calculated that a population size of 700 would be necessary to maintain 90% of the allelic diversity over the next 200 years. Kuo and Janzen (2004) suggest that it will be an easier task to maintain high levels of genetic diversity than to increase the level of genetic diversity once it is depauperate and advocate active management to increase adult survival and the number of turtles. Despite isolation and fragmentation of the study site, this population appears to be healthy in both a demographic and a genetic sense. For several reasons, however, we suggest caution in the management of this and similar turtle populations. First, like other populations of turtles, this population will be vulnerable to the removal of adults, whether through increases in mortality, collection for the pet trade (Dodd, 2001), or both. This is evident from a high estimate of c and an estimate of recruitment that is close to unity. A small decrease in adult survival would likely lead to a population decline. In addition, the analysis of Kuo and Janzen (2004) suggests that an increase in the size of the population will be necessary to ensure adequate genetic diversity for the long-term. Management DEMOGRAPHY AND CONSERVATION OF TERRAPENE ORNATA initiatives to increase recruitment into the adult population, whether through more strict protection of the study area or more manipulative efforts such as transplantation of adults from other areas (Kuo and Janzen, 2004), may be warranted. Headstarting will probably be of limited use considering the high estimate of c but could be useful if the annual survival rate of adults is stable and high (Heppell et al., 1996). Finally, from a methodological standpoint, the uncertainty associated with our estimates is a potential cause for concern. The 95% CI of our survival estimate includes values that are considered low for at least one population of T. ornata (Doroff and Keith, 1990) and that for our estimate of population growth rate includes values that would indicate population decline. Furthermore, the model selection uncertainty associated with our analysis means that our estimates of variation are underestimates (Burnham and Anderson, 2002). This study is one of only a few that presents rigorous estimates of survival and recruitment for an isolated turtle population in fragmented habitat. The combined use of demographic and genetic information to assess the conservation status of turtle populations is also rare. We advocate more studies of turtle populations in areas that receive intense human use to understand and combat the current global decline of many species (Gibbons et al., 2000). Acknowledgments.—We thank numerous members of the Janzen Lab and Turtle Camp crews for helping with specimen collection over the years. Animals were collected under permits from the Illinois DNR and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and in accordance with approved COAC protocols from Iowa State University. W. R. Clark, S. J. Converse, J. B. Iverson, D. L. Otis, and R. J. Spencer provided helpful comments on early drafts of the manuscript. KDB acknowledges the support of a Graduate College Fellowship from Iowa State University. The fieldwork in this long-term study was largely supported by National Science Foundation grants DEB-9629529 and DEB-0089680 to FJJ. This manuscript was completed while FJJ was a courtesy research associate in the Center for Ecology and Evolutionary Biology at the University of Oregon. LITERATURE CITED AKAIKE, H. 1973. Information theory as an extension of the maximum likelihood principle. In B. N. Petrov and F. Csaki (eds.), Second International Symposium on Information Theory, pp. 267–281. Akademiai Kiado, Budapest, Hungary. ANDERSON, D. R., K. P. BURNHAM, AND W. L. THOMPSON. 2000. Null hypothesis testing: problems, preva- 567 lence, and an alternative. Journal of Wildlife Management 64:912–923. BLAIR, W. F. 1976. Some aspects of the biology of the Ornate Box Turtle, Terrapene ornata. Southwestern Naturalist 21:89–104. BURKEY, T. V. 1995. Extinction rates in archipelagoes: implications for populations in fragmented habitats. Conservation Biology 9:527–541. BURNHAM, K. P., AND D. R. ANDERSON. 2002. Model Selection and Multimodel Inference: A Practical Information-theoretic Approach. Springer, New York. BURNHAM, K. P., D. R. ANDERSON, G. C. WHITE, C. BROWNIE, AND K. H. POLLOCK. 1987. Design and analysis methods for fish survival experiments based on release-recapture. American Fisheries Society Monograph 5:1–437. CAGLE, F. R. 1939. A system of marking turtles for future identification. Copeia 1939:170–173. CONGDON, J. D., A. E. DUNHAM, AND R. C. VAN LOBEN SELS. 1993. Delayed sexual maturity and demographics of Blanding’s Turtles (Emydoidea blandingii): implications for conservation and management of long-lived organisms. Conservation Biology 7:826–833. ———. 1994. Demographics of Common Snapping Turtles (Chelydra serpentina): implications for conservation and management of long-lived organisms. American Zoologist 34:397–408. CONVERSE, S. J., AND J. A. SAVIDGE. 2003. Ambient temperature, activity, and microhabitat use by Ornate Box turtles (Terrapene ornata ornata). Journal of Herpetology 37:665–670. CONVERSE, S. J., J. B. IVERSON, AND J. A. SAVIDGE. 2002. Activity, reproduction and overwintering behavior of Ornate Box Turtles (Terrapene ornata ornata) in the Nebraska Sandhills. American Midland Naturalist 148:416–422. CORMACK, R. M. 1964. Estimates of survival from the sighting of marked animals. Biometrika 51:429–438. DODD, C. K. 2001. North American Box Turtles: A Natural History. Univ. of Oklahoma Press, Norman. DOROFF, A. M., AND L. B. KEITH. 1990. Demography and ecology of an Ornate Box Turtle (Terrapene ornata) population in South-Central Wisconsin. Copeia 1990:387–399. FAHRIG, L. 2002. Effect of habitat fragmentation on the extinction threshold: a synthesis. Ecological Applications 12:346–353. FONNESBECK, C. J., AND C. K. DODD. 2003. Estimation of flattened Musk Turtle (Sternotherus depressus) survival, recapture, and recovery rate during and after a disease outbreak. Journal of Herpetology 37:602– 607. GIBBONS, J. W., D. E. SCOTT, T. J. RYAN, K. A. BUHLMANN, T. D. TUBERVILLE, B. S. METTS, J. L. GREENE, T. MILLS, Y. LEIDEN, S. POPPY, AND C. T. WINNE. 2000. The global decline of reptiles, déjà vu amphibians. Bioscience 50:653–666. HEPPELL, S. S. 1998. Application of life-history theory and population model analysis to turtle conservation. Copeia 1998:367–375. HEPPELL, S. S., L. B. CROWDER, AND D. T. CROUSE. 1996. Models to evaluate headstarting as a management tool for long-lived turtles. Ecological Applications 6:556–565. 568 K. D. BOWEN ET AL. HOELZEL, A. R. 1999. Impact of population bottlenecks on genetic variation and the importance of lifehistory: a case-study of the northern elephant seal. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society 68:23–29. HOKIT, D. G., AND L. C. BRANCH. 2003a. Associations between patch area and vital rates: consequences for local and regional populations. Ecological Applications 13:1060–1068. ———. 2003b. Habitat patch size affects demographics of the Florida Scrub Lizard (Sceloporus woodi). Journal of Herpetology 37:257–265. HURVICH, C. M., AND C.-L. TSAI. 1989. Regression and time series model selection in small samples. Biometrika 76:297–307. IVERSON, J. B. 1991. Patterns of survivorship in turtles (order Testudines). Canadian Journal of Zoology 69:385–391. JOLLY, G. M. 1965. Explicit estimates from capturerecapture data with both death and immigration— Stochastic model. Biometrika 52:225–247. KAZMAIER, R. T., E. C. HELLGREN, D. R. SYNATZSKE, AND J. C. RUTLEDGE. 2001. Mark-recapture analysis of population parameters in a Texas tortoise (Gopherus berlandieri) population in Southern Texas. Journal of Herpetology 35:410–417. KOLBE, J. J., AND F. J. JANZEN. 2002. Impact of nest-site selection on nest success and nest temperature in natural and disturbed habitats. Ecology 83:269–281. KUO, C.-H., AND F. J. JANZEN. 2004. Genetic effects of a persistent bottleneck on a natural population of Ornate Box Turtles (Terrapene ornata). Conservation Genetics 5:425–437. LANDE, R. 1993. Risks of population extinction from demographic and environmental stochasticity and random catastrophes. American Naturalist 142: 911–927. LANGTIMM, C. A., C. K. DODD, AND R. FRANZ. 1996. Estimates of abundance of Box Turtles (Terrapene carolina bauri) on a Florida island. Herpetologica 52:496–504. LEBRETON, J. D., K. P. BURNHAM, J. CLOBERT, AND D. R. ANDERSON. 1992. Modeling survival and testing biological hypotheses using marked animals: a unified approach with case studies. Ecological Monographs 62:67–118. LEGLER, J. M. 1960. Natural history of the Ornate Box turtle, Terrapene ornata ornata Agassiz. Univ. of Kansas Publications Museum of Natural History 11:527–669. LINDEMAN, P. V. 1990. Closed and open model estimates of abundance and tests of model assumptions for two populations of the turtle, Chrysemys picta. Journal of Herpetology 24:78–81. MITCHELL, J. C., AND M. W. KLEMENS. 2000. Primary and secondary effects of habitat alteration. In M. W. Klemens (ed.), Turtle Conservation, pp. 5–32. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington, DC. NICHOLS, J. D., J. E. HINES, J. D. LEBRETON, AND R. PRADEL. 2000. The relative contributions of demographic components to population growth: a direct estimation approach based on reverse-time capture-recapture. Ecology 81:3362–3376. PLUMMER, M. V. 2003. Activity and thermal ecology of the Box Turtle, Terrapene ornata, at its southwestern range limit in Arizona. Chelonian Conservation and Biology 4:569–577. POLLOCK, K. H., J. D. NICHOLS, C. BROWNIE, AND J. E. HINES . 1990. Statistical inference for capturerecapture experiments. Wildlife Monographs 107: 1–97. PRADEL, R. 1996. Utilization of capture-mark-recapture for the study of recruitment and population growth rate. Biometrics 52:703–709. RUBIN, C. S., R. E. WARNER, J. L. BOUZAT, AND K. N. PAIGE. 2001. Population genetic structure of Blanding’s Turtles (Emydoidea blandingii) in an urban landscape. Biological Conservation 99:323–330. RUBIN, C. S., R. E. WARNER, D. R. LUDWIG, AND R. THIEL. 2004. Survival and population structure of Blanding’s Turtles (Emydoidea blandingii) in two suburban Chicago forest preserves. Natural Areas Journal 24:44–48. SCHWARTZ, E. R., C. W. SCHWARTZ, AND A. R. KEISTER. 1984. The Three-Toed Box Turtle in central Missouri. Part II. A nineteen-year study of home range, movements, and population. Publications of the Missouri Department of Conservation Terrestrial Series 12:1–29. SEBER, G. A. F. 1965. A note on the multiple recapture census. Biometrika 52:249–259. WHITE, G. C., AND K. P. BURNHAM. 1999. Program MARK: survival estimation from populations of marked animals. Bird Study 46:120–139. WILLIAMS, B. K., J. D. NICHOLS, AND M. J. CONROY. 2002. Analysis and Management of Animal Populations: Modeling, Estimation, and Decision Making. Academic Press, San Diego, CA. Accepted: 25 August 2004.