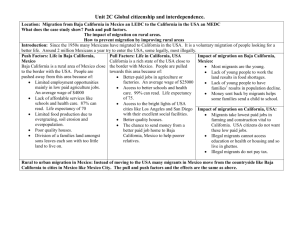

A w

advertisement