~ ~~' ~ITna Thall

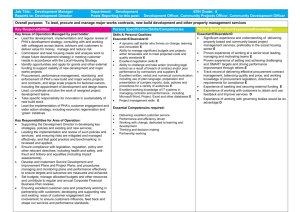

advertisement