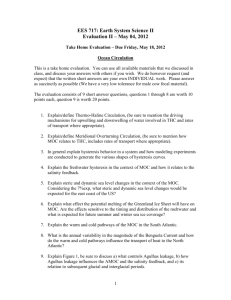

>/Departnent .'-'0 . .F..

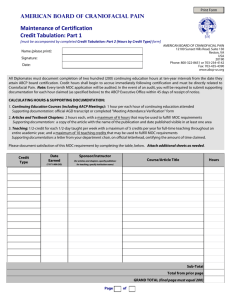

advertisement