1973

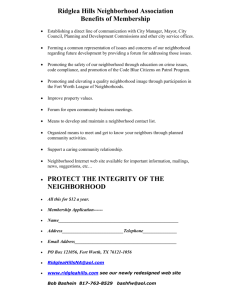

advertisement