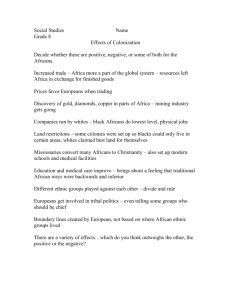

© A HOUSING SOUTH by

advertisement