Document 10637651

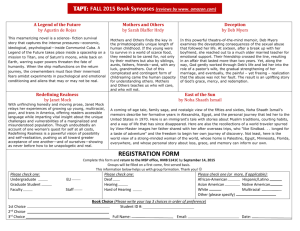

advertisement