by (1976) Submitted to the Department of

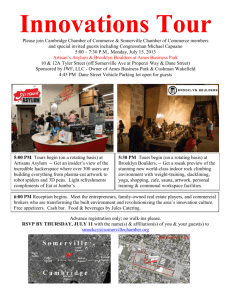

advertisement