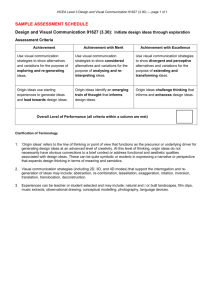

Process City Housing Shoii M.Arch., Waseda University, 1974

advertisement

Process of Desiqning City Housing in Japan

by

Shoii Kurokawa

M.Arch., Waseda University, 1974

B.Arch., Waseda University, 1972

Submitted to the Department of Architecture in partial fulfillment of the requirement of the

degree of Master of Science in Architecture Studies at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

June 1983

@ Shoji Kurokawa

1983

The author hereby grants to M.I.T. permission to reproduce and distribute copies of this

thesis documont in whole or in part.

Signature of Author .. . .

..

g

.

.,

.......... ...............

Shoji Kurokawa,

..

*.*

..

. .*

Department of Architecture

...............

e

May 6, 1983

Certified by ...................................................................................

N. John Habraken

Professor of Architecture

Thesis Supervisor

Accepted by.

........

MA SSA CHUSE TTS INSITUTE

OF TECHNOLOGY

N. John Habraken,

Chairman

Departmental Comnittee on Graduate Students

MAY 26 1983

LIBRARIES

1

Process of Designing City Housing in Japan

by

Shoji Kurokawa

Submitted to the Department of Architecture on May 6, 1983 in partial fulfillment of the

requirement for the degree of Master of Science in Architecture

Studies.

ABSTRACT

The purpose of this thesis is to show one design approach to providing more preferable

housing for users in

Japan.

Chapter 1 gives an overview of trends in Japanese housing construction, describes user

requirements, analyzes problems in a case study, and suggests fundamental principles of design

to guide future design decisions.

In Chapter 2, the design process is developed by resolving issues at the larger, community

level and scaling down to the individual houseolan level.

Chapter 3 analyzes an existing Japanese housing project chosen as a case study, and

illustrates alternative solutions based on the design principles described in the preceeding

chapters.

Finally, unresolved issues and future housina concepts are discussed in the concluding

chapter.

Thesis Supervisor:

N. John Habraken

Title:

Professor of Architecture

2

ACKNCWLEDGEMENTS

This thesis was made possible with the advice, help, encouragement and support of many

people.

I would like to acknowledge and express my sincerest thanks to the following people:

Prof. N. John Habraken

Prof. Nabeel Hamdi

Prof. Shun Kanda

Prof. Sandra Howell

In particular,

I would like to thank my thesis advisor, Professor N. John Habraken,

guided and advised me in

who

this effort during the past two years; and Professor Nabeel Hamdi

who gave me the opportunity to focus my interest in

traditional Japanese housing.

housing design through research of

I would also like to express my deepest appreciation and

thanks to Dr. Christopher Sawyer-Laucanno,

Barbara Smith and John Willand.

3

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

........................-...-

IN'RCDUCTION .................

1.

2.

....- .

....

... .............

2

.

-.

3

.

-.

5

PROBLEM ANALYSIS

e........................---

7

.

1.1

User Needs. .

1.2

Design Problems in a Case Study

... ... ...

10

1.3

Principles Guiding Housing Design .......

16

DESIGN STUDY FOR ALTERNATIVE SOLUTIONS

2.1

Block Model

(Neighborhood)

2.11

Block Model......................

19

2.12

Site Application ..................

25

2.2

Access ................................

2.3

House Plan

2.4

3.

-

- - - - - - ...... -...........--

ABST ACTR...........................-------.------

28

2.31

Analysis of Space Organization ...

36

2.32

House Plan for Fach Access Type

40

2.33

Additional Floor Plan Variations

58

2.34

Facade Variations

................

67

Open Space .............................

68

COMPARISON

3.1

Coparison with Moroe Apartments .......

3.2

The Decision Making Process ............

...

..

...

.... .....

..

...

..

-- ..

..

.--

..-

..

-.

--

--.

---

000

---------------

-- --

---

-- --

76

83

CONCLUSION .....................................

86

BIBLIOGRAPHY ....................................

87

4

INTRODUCTION

Observation

In response to the pressure of increasing urban population, all the available land within

cammuting distance by rail of many Japanese cities has been developed.

A recent movement to

increase density in the city has resulted in many housing projects springing up in former factory

sites, and in residential areas formerly made up of single family/low density housing.

In these housing situations, residents require not only adequate space, but also space

that answers their own dwelling requirements.

Architects, Planners and Developers are neglecting

various user needs when only uniform housing is provided.

The increasing popularity of housing

cooperatives proves that the Japanese public does not expect its housing to be uniform.

Purpose

Judging by the overall design of Japanese housing, it appears that user needs are treated

as secondary to so-called economic efficiency.

Users are forced to buy "completed" houses

constructed with almost no variation in access, houseplan and open space.

Reasons such as

mechanization of construction, standardization and mass production are given for this type of

design.

However, multi-tenant housing need not preclude alternative solutions.

This is

the time to develope alternative design solutions and their related decision making process.

5

.

PIROBLEM ANALYSIS

1.1

User Needs

1.2

Design Problems in a Case Study

1.3

Principles Guiding Housing Design

6

1.

PROBLEM ANALYSIS

1.1

User Needs

Fig. 1

Percentage of Families Not Satisfied with their Housing

(N=32,092)

Since the middle of the 1970's, it has been said

that the crux of housing problem in Japan has becom

0

50

100%

issatisfi

Satisfied

the issue of quality vs quantity.

60.4

Extremely Dissatisfied

5.5 -J

No Opinion

0.7

According to government housing statistics in 1978,

the total number of houses exceeded the total number of

families by 8%. This means that there are approximately

2.7 million vacant houses nationwide.

In the same year, a poll taken by the Ministry of

Construction revealed that 40% of users were not satisfied

with their housing and desired such improvements as increased living space, sunny exposure and related amenities.

(Fig. 1, 2)

100%

12,000

- 75

8,000

50

4,000

25

Before the Oil Crisis, housing construction rose

steadily. Following its initial drop after the Crisis,

construction began to stabilize. The current trend in

housing construction is expected to continue as illustrated in Fig. 3.

Fig. 2

(N=12,482)

Reasons for Dissatisfaction with Current Housing

Source:

"Statistics of User's Housing Requirements",

Japanese Ministry of Construction,

1978.

7

The dream of most Japanese is

to have their own home.

Due to exorbitant land costs and overpopulation, most

people must settle for mass housing.

It

Fig. 3

is important to note the recent decrease in

rental housing in favor of condominiums,

Trends in Housing Construction in Japan

million

1.00

implied in

Fig. 3.

Detached Houses

Condominiums,

said to be a representative type of

0.50

housing in Japan, have been built primarily in the three

largest cities:

Condominiums

---''~4-

(Fig. 4)

--

Rented Houses

o 'Ibkyo--with almost 50% of all condominiums built

o Osaka--30%

75

76

77

78

79

80

o Nagoya--5%

81

(Pstimated)

Source:

Statistics of Housing Construction,

Ministry of Construction, 1980.

This concentration shows condominium housing to be

considerably nore popular than rental housing in

large

Fig. 4 Trends in Condcmiinium Housing

(Area Statistics)

x 10,000

Japanese cities.

Tokyo Area

Responding to this trend, the Japan Housing Cooper-

ation, a public authority, has begun to develop condominium standards.

a 3 bedroom,

86 m2

~~

-...-----

Nagoya Area

For example, the floor area standard for

4-person family condominium is

which is

Osaka Area

2

more than

75

76

77

78

79

80

larger than the present housing averaqe.

In addition to increased floor area, other elements

Source:

Institute of Real Estate Econcimy, 1980.

such as sunny exposure, improved HVAC systems, all-

8

weather insulation and noise reduction insulation are expected to be major quality improvements.

Fig. 2 illustrates eight areas of dissatisfaction among users.

Although each is closely related

to one another, they can be divided into such broad categories as: design,

concerns,

and economic issues.

Floor area,

garden area, good exposure,

technical and social

ventilation and privacy can

all be considered aspects of design.

Technical concerns include building and mechanical systems maintenance and noise reduction,

as they relate to building materials and equipment.

Environmental problems caused by vehicle exhaust

and industrial pollution are considered social concerns.

Construction costs and rent are economic

issues.

The architect is most concerned with the four items highlighted in the design category which

are the main subjects to be discussed in

this thesis.

The issue of "floor area" can be interpreted as the need for alternative floor plans based on

different family size and spacial needs.

"Garden area" can be understood as the issue of open space.

"Sunny exposure" and "ventilation" depend on layouts within the block plan, and configuration of the

house plan.

"Privacy" is the relation between dwelling space and access.

Previously, this kind of analysis was neglected by developers pressured by so-called economic

efficiency.

Despite reservations, users had to compromise and buy "campleted" houses while dream-

ing of somday building their own detached house to reflect individual needs and desires.

High

land costs, excessive commuting time and related inconveniences in Japanese cities discourage this

dream.

Given these obstacles, the recent phenomenon of housing cooperatives has appeared.

In this in-

9

stance, a group of people build housing by collectively sharing construction costs and land ownership.

Tenants participate in the decision making process as much as possible, a fact which has beccme a

cause celebre. Housing cooperatives would not have grown in such popularity if they did not indicate

dissatisfaction with current housing choices.

1.2

DESIGN PROBLEMS IN A CASE STUDY

To further the general analysis in section 1.1, actual problems are studied through analysis of

a recent housing project in Japan.

Most housing projects constructed in large cities are high-rise apartments built on small lots,

with less and less land available to them.

Since alost all available land existing in large cities

is covered with high-rise buildings, new housing construction sites are extremely limited. However,

in residential areas which have building elevation controlled by zoning codes, low-rise housing has

already appeared in Japan.

To illustrate this trend, I chose to analyze a recently completed housing project in Kanazawa,

Japan called Moroe Apartments.

The project was based on the two criteria described in

the preceding

paragraph:

a)

low-rise housing

b)

scale of development at the neighborhood level

Discussion of the characteristics and problems of Moroe Apartments is based on the description,

photographs, and plans appearing in the July 1982 issue of JA, The Japan Architect.

Therefore,

the information available is not detailed, but of a general nature.

10

MOROE APARTMENTS

1. Block Plan (neighborhood scale)

The architect's consideration for townscape and locality make the enclosineg layout of this

project acceptable.

sunny exposure.

However, the N-S orientation is not the best solution when considerinq

Some units have a definite disadvantage when sunny exposure is not appropriate

to user needs.

2.

Access

Individual staircases for access to each lower unit in a multi-unit scheme is a very new

concept in Japan and most effective for providing privacy.

For the upper units, a single gallery

type corridor provides direct access to all the units,

this case.

3.

Privacy is a problem in

The difference between the ambience of the lower and upper units is too great.

Floor Plans

The layout is

such that only one floor plan for lower, upper, and corner units is

provided.

No variations which respond to individual user needs is evident.

4.

Open Space

Upper units have no garden, a fundamental need according to the housing polls taken.

use of the park adjacent to the complex could pose security problems to tenants.

area for upper units is

Public

The commron park-

not desirable for users whose cars must be parked a distance from their

unit, risking vandalism.

11

OUTLINE OF MOROE APARIMENTS

View of Front Elevation

s

Background v

Located in the city of Kanazawa, the Morob

Apartments are operated by Ishikawa Prefecture.

This part of Japan has a severe climate with

high humidity and heavy rains and snows. In addition, the city of Kanazawa has a distinctive

culture and life style manifested in characteristically local ideas about housing. These ideas

had to be included in the design of the apartment project. In addition, in this instance,

Masaya Fujimoto, who represents the Gendai

Keikaku Architectural and Planning Office

and his group, have applied experience

gained in similar work beginning with the Rokuban-ike Apartments (JA, October, 1976) on

many other themes, including intimate contacts

with earth and with greenery, continuity with the

urban setting, harmony with the entire district,

disaster prevention in multilevel dwelling blocks,

and adaptability to future change. Of course,

to this list must be added the various needs

of the dwellers. The goal of their efforts is to

produce apartment projects of a richly urban

nature. The key concept for the realization of

their goal in the case of the Morob Apartments is that of a multilevel townhouse.

The basic unit of the project is a pair of apart-

ments, one on top of the other. The lower

maisonette apartments face the street, and each

has its own entranceway and front and rear garden spaces. These units are lined up in continuous

rows. The front garden spaces are largely consumed by parking lots. The rear gardens, which

provide places for contact with earth and plants,

are enclosed by means of hedges. The upper

single-level apartments face an open passageway on the third floor. This elevated street~like space (six meters above ground) is a horizontal connector ex tending throughout the entire

project.

Part of the passage houses storage space for

baby carriages and other such domestic equipment. In addition, planter boxes have been

installed; and there are plans to line the

passage with shrubs and flowers. Four staircase

towers and a ramp for baby carriages connect

the passageways with ground level.

Oriented toward the surrounding roads, the

apartment blocks employ a placement method

similar to the one seen in old-fashioned Kyoto

townhouses. The reason for using this arrange.

ment, which dif leres from the kind of placement

seen in most Japanese apartment settlements,

is to establish bonds of community between the

apartment buildings and the surrounding urban

neighborhood. It is said that in Kanazawa,

clearing roads of winter snows must be a com

munal project. Opening the apartments on the

wooden houses on the opposite sides of the roads

and on the rest of the surroundings by means

of the townhouse placement makes joint endeav

ors of this kind easier.

Data

MORO APAR TMENTS/Kanazawa, Ishikawa

Prefecture; planning: Building and Housing

Division of the Ishikawa Prefectural Civil En

gineering Bureau; architects: Gendai Keikaku

Architectural and Planning Office; structural

engineers: Shigeru Aoki and Associates, Hosei

University; mechanical engineers: Goi Architec.

tural Design Institute; site area: 12,455.1712,

building area: 3,896.00m 2 ; total floor area:

9,329,29mn2 ; general contractors: K ito Kensetsui

Co., Ltd.; Hori Komuten Co., Ltd.; Toyokuragumi Co., Ltd.; Takeda Doken Co., Ltd.; and

Hokkoku Kensetsu Co., Ltd.; completion date:

March, 1980.

Photos: Masao Arai, Photography Dept., JA.

The Japan Architect, July 1982.

12

FIRST FLOOR PLAN OF MOROE APARTMENTS

N

-

wI

Firsi-floor plan; scale: 1/1,000.

13

SECTION AND SECOND FLOOR PLAN OF MOROE APARTMENTS

A-A Section; scale: 1/500.

N

r $ i 111

~nIr

Second-floor plan.

14

SECTON AND THIRD FlOOR PLAN OF MOIOE APARINENTS

-

-

- _

--

_-

tUTTf

_-'_

-

~

T§

4

IT

li

B-B Section.

Third-floor plan.

15

1. 3

PRINCIPLES GUIDING HOUSING DESIGN

In analyzing the demands of prospective residents, we can assume that these.demands are closely

related to the attributes of free-standing houses in suburban areas, to which is added proximity

to work, school and urban facilities available to city dwellers.

We can identify those elements of suburban housing which residents want to find in their city

dwelling as:

1.

Sunny exposure... each house has southern exposure

2.

Access... each house has its own access creating a sense of privacy and ownership

3.

Floor Plan.. .each house has possible variations in plan, subject to family size and life

style

4.

Garden... each house has a garden facing south

5.

Parking space.. .each house has its own parking space adjacent to the dwelling.

These five elements found lacking in

Moroe Apartments are to be considered in

the following

design proposal.

To provide a realistic design application and test the previously proposed design principles,

I have chosen the given site configuration and program of Moroe Apartments as the basis of my study.

In addition to evaluating the existing solution and exploring alternative solutions, I will introduce

additional criteria not part of the original plan.

The following are assumed premises:

1. the 1.2 hectare urban site is residentially zoned

2. buildings on the site are limited to 10m maximum height by building code

16

3. density is 300 people/ha and on an average of 4 people/family

4. the floor area is more than 86m 2/unit

SITE

I

-I

I

61

F

o

10

30

---

]

F

50M

17

2.

DESIGN STUDY FOR ALTERNATIVE SOLUTIONS

2.1

Block Plan (Neighborhood)

2.11

Block Model

2.12

Site Application

2.2

Access

2.3

House Plan

2.4

2.31

Analysis of Space Organization

2.32

House Plan for Each Access Type

2.33

Additional Floor Plan Variations

2.34

Facade Variations

Open Space

18

2.1

BLOCK PLAN (NEIGHBORHOOD)

Analysis of Moroe Apartments begins at the neighborhood level, which most closely relates to an

urban application.

Using the principles and premise outlined in Chapter 1, this study is divided

into two parts:

1.

development of block nodels as a general solution, to which is added good exposure, private

access, increased living space, garden and adjacent parking

2.

2.11

application of these block nodels to the case study site.

Block Model

1)

Block Model 1

- Elevation is three floors according to compliance with zoning code height limitations.

- Housing units consist of a flat type (1st floor) and a maisonette type (2nd, 3rd floor).

The floor area is approximately 100m2 (15m x 6.3m for the lower units; 9m x 6.3m x 2

stories for the upper units).

Each lower unit has a front yard facing south;

each

upper unit has the sam sized garden located on the roof of the lower units.

- Parking is provided in front of each unit.

- Access for each unit is provided individually.

- For increased privacy,

each dwelling unit has its

backyard facing the backyard of

the opposite building.

- A single block model consists of two housing units in the N-S orientation, and 10

units in the S-N orientation.

In a large complex of multiple blocks, different con-

figurations can be made by manipulating street dimensions.

2)

Block Model 2

Adhering to the same principles as Block Model 1, Block Model 2 shows another possible

block layout.

This model consists of two, four-unit blocks of Block Model 1 in the N-S

19

orientation connected by an alley instead of a street.

The main issue in this layout

is how to provide parking spaces for adjacent inner units;

by housing units are proposed as a solution.

parking spaces enclosed by

The open space created is

not only for

parking, but can be utilized as a play lot or conmunal space.

20

MODEL 1

- Uper- Un-itL.owesr- Unr'r+-

C '21 ",

IBa" )

Section

I

~IccA~.

1

n4 Pco%-

v

v-F--FI

I

I

I

Iff

0

3

6

2

IS0"

I

II

I

1

I-

I

UriW

VTlF

7

II

-irnon-I

upper

HcQxim ur

I

Section

v ErL.

2

21

MODEL 1

2

~P3t-1

31-m

IV

T

C=b-

111z"

.Le -

T~ cq" -&") T

G"

4k

IF

G" (9

J

N

is"

IF

-I-

I-

Smveet

22

MODEL 2

0-.:a

I --

I-

E9

h~AI4Z~I

CL--"

24"

S-tTet

~~,I~C-Ezr%&erA

DtaeI'en

CGmr-Ckeri

Unitr

Pvs-linl

tA

4- A. i I

Unit-

-i-

-

Z4-m

-J

AI a

24-"

eIN

Section

1 e~..k

1

cB'1

I Uri.-r.

3

Section

2

23

Ez~ N

MODEL 2

4~8~1

(21t4-.

LJwrl1TTC~~Tl

l

]m

~3~M

1

L

C21".

2

16- )

Model 2

Plan

24

2.12

Site Application

1)

Site Model 1

Block Model 1 is applied to the actual case study site.

Since the required density is

satisfied by 90 units; ccnmunal space can be provided in the remaining area.

In this site

plan, 14 units can be installed in the E-W orientation with open space provided in the

2)

middle.

This open space is effective for outdoor walkways,

garden.

Every housing unit satisfies the principles and premise of Block Model 1.

a conmunal facility or a public

Site Model 2

Block Model 2 works well in

both the east and west side.

this site except for some deformation of parking spaces at

(Block Model 2 has four more units than Block Model 1,

additional parking is required.)

so

An alley in the middle of the site connects the east and

west parkinq areas; spacial continuity of the N-S orientation is provided by internal open

space and staggered parking.

25

O8N

I

ILl______

7E

o io

20 3050M

Site Model 1

26

&N

Lii

1U

~~1

o

10

r--T I

20

30

F -- -

50 M

Site mobdel 2

27

2.2

ACCESS

In a N-S orientation, there are three fundamental patterns of access which give users a sense of

1) south, 2) north and 3) side.

ownership:

Since each unit plan is

influenced by the location of its

entrance, the following three patterns were developed:

1) Access from the south..............

Access Model 1, 2, 3, 4

2)

Access from the north..............

Access Model 5, 6, 7, 8

3)

Access from either side............

Access Model 9

The characteristics of each model are illustrated in the 1st and 2nd Floor Plans and Cross Sections.

(See Fig.5-13

).

Access Model 1

This type of access is shared by 4 housing units (2 lower units and 2 upper units).

1st floor, an open staircase is

On the

provided between the two entrance doors for the lower units;

two entrance doors for upper units are situated next to each other.

the

The staircase wall should be

high enough to prohibit visual access into the lower unit gardens.

Access Model 2

This type of access is provided for two housinq units:

pair.

one stair per lower and upper unit

The entrance for the lower unit and staircase for the upper unit are situated next to one

another.

In contrast to Access Model 1, each unit pair has its own access and staircase, which

affords greater privacy.

28

Access Model 3

This access type is a conpromise between Access Model 1 and 2.

The segregation of upper unit

By

staircases and lower unit entrances incorporates the best features of Access Model 1 and 2.

conserving staircase and access space, internal space of the dwelling unit is increased,and the

same privacy afforded in Access Model 2 is preserved.

Access Model 4

The difference of this type fram Access Models 1,

2, and 3 is apparent on the 2nd floor.

single staircase is provided for several units with a gallery-type corridor connecting them.

corridor creates the same relationship between access and open space as on the 1st floor.

access to the 2nd floor is gained from either end of the building which makes it

A

This

Also

quite flexible.

29

Access model 2

Access Model 1

PLCe1 I

3

U

..---- r'

Pa~-.kI r~3

;+

Sweer

Section

Urper

Grcar~~

L~~

N

-------2nd Floor Plan

Streaetsecra

-II----

2

41

o

lst

0

.

- w .

Floor Plan

-W

30

Access Model 3

Access Model 4

U

LU

m ,-

ei-w

t

EUt-k'3

fee-w.ing

Section

.1'--~~'

Lu~~

N

f

pm,

2nd Floor Plan

Si-reer

Se-ri

sew~ion

Sec.on

S4~t4e%~

t_-

Floor Plan

1

L

Ac

;=I 43.

31

Access Model 5

The relationship between the entrances for lower units and staircase for the upper units is the

same as in Access Model 1,

except that the direction of access is

fram the north.

Due to the ab-

sence of gardens on the 2nd floor on this side, the landing becoms dark despite the open stair.

Access Model 6

However,

The relationship between entrance and staircase is almost identical to Access Model 2.

in this case the stair could be enclosed and the entrance door for the upper unit could be located

on the 1st floor. Each upper unit would have to have its own entry hall at the top of the stair.

Access Model 7

The relation between entrance and staircase most closely resembles Access Model 3.

type shares the privacy and increased dwelling space of Access Models 5 and 6.

However,

This access

it

also

has the problem of darkness on the landing.

Access Model 8

What distinguishes this type from the others is

floor.

A large open space is

the arrangement of landing space on the second

provided on the 2nd floor, and at the same time, the staircase is

pushed further toward the street.

This arrangement not only gives light, but also effectively

articulates the north elevation.

32

Access Model 6

Access Model 5

F

S-rt-emi

Fik4'~r%

L-oLL~e%- Ur~h,-t~

Section

s-it-t

Rbr41Ir3

upper- U.r

N

2nd Floor Plan

I,.

Seenon

Sect-ion

HI

lst Floor Plan

33

Access Model 8

Access Model 7

or L

DThe

i n*

Unit-

Section

o

North Elevation

N

C

Pq0"

2nd Floor Plan

St-rea+

zo-1

st-reet

on

lst Floor Plan

0 1 2

l ch4

4z~. II

r-,.

12

34

Access Model 9

This type of access is for units which face open spaces like streets and parking spaces. The

entrance for lower units could be the same as Models 1-4 from the south, and Models 5-8 fram the

Access for the upper units is provided fran either side of the building. This kind of

access type allows not only variation in access, but also adds interest to the townscape instead of

providing monotonous walls. Privacy is well controlled in this access type.

north.

35

2.3

House Plans

Analysis of Space Organization

2.31

The size of housing units in the block plan is based on the following sketch. This rough

plan utilizes the analysis of location and interior dimensions described in this section.

O

Legend

L

Living Rom

B1

Single Bedroom

B2

Double Bedroom

D

Dining Boom

K

Kitchen

E

Main Entrance

Br

Full Bath

Bt

Half Bath

lower Unit

St

Storage

y

Upper Unit

3rd Floor Plan

3

2nd Floor Plan

q

.- -

-2.

.-.-

lst Floor Plan

36

Space and Function Analysis

Living Room (L)

14---

Dining Room (D)

3.3

{+---3 -0--4

Double Bedroom (B2 )

KU

V

3.0

2. 7

--,iiz33

3.0

Single Bedroom (B1 )

L

I

I-

[-

251

Kitchen (K1 )

2,1 x 2r7

x 3.O

x3.6

Entrance (E)

Bathroom

Dining Kitchen (K2 )

.3ko

"'3

2rv

-4

K

U1. ±

Ur4IoorQ3

4tocrocJ

Half Bath (Bt)

3,0x 4--2

I.xS.O

Closet

CI

O A x 1.-5

C.

C:>3tV

CI cokShQl+

CO60%

Full Bath (Br)

d

C- I ose+t

0.9

37

A zone distribution is a system of zones and margins, the relative

Zoning Analysis

positions of which follow certain conventions.

An a zone is an interior area, intended for private use, and is

ajacent to an external wall.

A V zone is an internal area, intended

for private use, and is not adjacent to an external wall.

A X zone can be internal or external but is intended for public use.

A 6 zone is an external area intended for private use.

A margin is an area between two zones with the characteristics of

both of these zones and taking its name from them.......... VARIATIONS

Lrower Unit

0

946

Upper Unit

-41

0l6 6o0

qo

loGo

2'o

a Zio

d oo

IIIID

120

in

P61 210

0 2300

q0

_______.Sr 60

d5 pl

lst

Floor

2nd Floor

0(

300

c4 X60

3rd Floor

38

A sector is a part of a zone and its adjoining margins that can be

Sector Analysis

planned freely.

A sector group is

VARIATIONS

a combination of connected sectors........

Upper Unit

Lower Unit

CAL-

CL~

rb M 30

L...

4:C

60

210

AO

2210

Cko

VW9120

ti

qo

6co

D C0300

0C

S

lst

2nd Floor

3rd Floor

o

Floor

r>/ K

39

2.32

Floor Plan for EAch Access

In this section, basic floor plan variations and their sub-variations are studied

according to one of these access types: 1) south, 2) north, and 3) side.

b's qo

A20

2.1

22

otaiSO

K/E

e'/8'

2.

q0

Basic Variation

Sub-Variation

A basic variation indicates the

A sub-variation of a vasic variation

position, in a specific sector

is a completed layout in which the

group, of a certain group of

positions of the functions are the

functions, which together form

same as in the basic variation.

a dwelling program.

......

VARIATIONS

40

The design premis

for Basic Variation and Sub-Variation Floor Plans is

as follows:

1)

location of entrance and staircase is fixed in the same access type.

2)

The living room always faces south in

the lower units, and is

located on the southern

side of the 2nd floor in the upper units.

Please note that the Basic Variations are-indicated by symbols for eadh room type.

41

Basic Variations for Access Model 1 from the South

3rd Floor

2nd Floor

lst Floor

1)

I)

1)

I

Ba.

;zILiiI

L

2)

-J-

3)

~

2)

2.)

3)

3)

az ,

'-I

L

K

Iower Unit

Upper Unit

42

Sub-Variation for Access Model 1 from the South

lst

1)

Floor Plans for lower Units

2)

3)

rLWO

paJB

210

pi'210

d4y

qo

Lower Units

43

Sub- Variations for Access Model 1 from the South

lst

4:)

Floor Plans for lower Units

S

300

Qo

2.10

WW

1 2.0

qo

O

Odqo

Lower Units

44

Sub - Variations for Access Model 1 frcan the South

2nd and 3rd Floor Plans for Upper Units

( 210

go

.2,)

3)3rd

Floor

9(30

300

A

2nd Floor

45

Basic Variations for Access Model 8 from the North

3rd Floor

2nd Floor

lst Floor

4-)I

1)

Ki

1)

4-1

t)

E

L3

L.

L

ai

2)

z)

B,

.

E

L

-1

B2

a)

lwer Units

Upper Units

46

Sub- Variations for Access Model 8 frcrn the North

lst Floor Plans for Iawer Units

-A~

qO

c3q

,

IET

12.0

a, aio

ST

C

o'

'o

I(coo

I)

2)

3)

4L)

47

Sub-Variations for Access Model 8 fran the North

2nd and 3rd Plans for Upper Units

I

-C'I

3)

-3)

4)

48

Basic Variations for Access Model 9 fran Either Side

1)

B.

3rd Floor

2nd Floor

1st Floor

A-)

Ki

I

BI

B

B

St

B2B I

at

~2.

A1

K1

IN

L

4-

3)

B.

B)

E

Lower Units

Upper Units

49

Sub- Variations for Access Model 9 frcn Either Side

1st Floor Plans for

Iwer Units

S3300

40o

dp qO

____

@t

Q0

50

Sub-Variations for Access Mbdel 9 fran Either Side

1st Floor Plans for Iower Units

4-)

2610

12o

Qo

51

Sub-Variations for Access Model 9 from Either Side

2nd and 3rd Floor Plans for Upper Units

.860

in

qo

3rd Floor

2n

F

210

a 40.

2nd Floor

52

Based on the analysis of floor plans in section 2.32, the following drawings show the support

structure (illustrated by heavy lines) and anticipated wall lines (illustrated by dotted lines).

Both internal and external staircases are a part of the support structure.

Fig.17,l8show the assembled support structure.

Support Structure for Access Model 1 from the South

gi

*g'

Ii

'~1

I'

'a

-

I-

I'

It

Ii

-~

-4119

Ewhvrxce

2nd Floor

3rd Floor

Upper Unit

lst Floor

Iower Unit

Fig. 14

E ru-mnc-e

53

Support Structure for Access Model 8 frcn the North

entrance

7

*

I1L~

~I

a

I

Lj

jfljj~

aTm~

aI

all

a

~

-

a

'a

II

a

*

ixi~

a

~

IJ

I

2nd Floor

i

a

*

7-

4-r.1

a

*

*j

I

Upper Unit

a

~

a

*

3rd Floor

II

II

lst Floor

Lower Unit

Fig.15

54

Structure for Access Model 9 fran Either Side

7777IL~

II

in

:1

'a

~~~~1~'aa,

*

I

at

* I

l.a

I'

.1,1

*1

-

a''a-i-I>

*

II

*

a'

a

*

SI

-

I' * ~

I

I

I

Upper Unit

f

I

I

*'

1st Floor

(I

e~

*~

Lcwer Unit

II

~

I~

Ii

I,

--

-

2i1[I:X.

Fig. 16

55

Support Structure for Access Model 1 and9 fron the South and Either Side

ML

-u-----

max

or

U

L-

a,-w - -*

m

-

- -m--"

m

-k-

-

Fig.17

m

u

E*

f

m

-

TI

t -

-

3rd Floor

71

_______U.

- -,

U

m

-

a

U

I

-

-

U

U

-

K"A 7

IU~~ ~.,iII

1

H

-

U

w

m

-

W

.

N ~

WEI

IIt"~

E1UZL.L~L

El

2nd Floor

lst

Floor

56

Support Structure for Access Model 8 and 9 fran the North and Either Side

Fig.18

3rd Floor

57

2.33

Additional Floor Plan Variations

So far, the study of floor plans has been contained within the predetermined party

walls which has limited the number of variations.

However, by providing openings in the

party wall, it is possible to develop many more housing unit variations with different floor

areas and configurations.

The following drawings show several variations ranging from a 4-bedroom to a studio

unit in both the lower and upper units.

or less, and closed if not needed.

Openings in the party wall are limited to three

This makes it possible to create multi-level units.

58

Additional Floor Plan Variations for Access Mbdel 1 and 9 fran the South and Either Side

4 Bedroan Type

2nd Floor

lst Floor

59

Additional Floor Plan Variations for Access Model 1 and 9 fran the South and Either Side

3 Bedroan Type

3rd Floor

L

2nd Floor

60

Additional Floor Plan Variations for Access Model 1 and 9 from the South and Either Side

2 Bedrocm Type

J1

-.

2nd Floor

61

dditional Floor Plan Variations for Access Mxel 1 and 9 fran the South and Either Side

1 Bedroan Type and Studio Iype

3rd Floor

2nd Floor

1 Bedroom Type

"" 1st Floor

*OM

Studio Type

-

62

Additional Floor Plan Variations for Access Model 8 and 9 frcan the North and Either Side

4 Bedroam lype

1st Floor

63

Additional Floor Plan Variations for Access Model 8 and 9 fran the North and Either Side

3 Bedroan Type

1st Floor

64

Additional Floor Plan Variations for Access Model 8 and 9 fran the North and Either Side

2 Bedroam Type

1st Floor

65

Additional Floor Plan Variations for Access 4 odel 8 and 9 fran the North and Either Side

1 Bedroan Type and Studio Type

........

_--lst

Floor

66

2.34

Facade Variations

There are two ways to consider the facade:

structure, or

exist for both

1) to make it

a fixed part of the support

2) to leave the decision to users as a part of the infill units.

Variations

1) and 2) as seen in Fig. 19.

67

2.4

Open Space

The study of open space is divided into private space and public space.

deals with access variations to the private garden.

Private space

Public space incorporates street, side-

walk, parking and alleyways.

Additional Access Variations

Access Model 1

Variation

3)

lst

Floor

Variation

1)

4)

2)

5)

68

Additional Access Variations

Access Model 1

2nd Floor

Variation

1)

Dwelling

Unit

Variation

3)

69

Additional Access Variations

Access Model 8

Access

lst Floor

Variation

2)

1)

FGarden

Dwelling

Unit

Access Model 8

2nd Floor

Variation

1)

Access Model 9

Variation

1)

Dwelling

Unit

Staircase

70

Proposed Street Configurations for 12 ,9 and 6m Streets

2

91)

12m

1)

1d

1

I

2)

-

qc

2)

6m

IL

----

I

MMIZAP"Aff&'IMPNF

.1- 11

1

C4ZZ

Wiwi

~

H.'

U

S

w

I-il

2)

L

I

P -'efer-edl Mis-%'nm

-O-r- 2 ccxr-'S

<4a.

3)

J=77==6

I-

rl

I-c3O'l-c;O,,

Jl-

,2

71

Parking variation 1

4Z-

iPA$YZIN~Zt,1

6tc,

PRp-r-,ep

Grctr-vAeni

vj t- IIUnI

MAn-%mumr

72

Parking Variation 2

2

v~s.

I

-

L.

r-5Spox-e

48

&ScdQ uajaIK

um'..'r

Enmr-e~

, .N .. 4

i 2i

W.

Section

lst

~c&e.

W)clK

Floor Plan

Cheliev Luo

73

Alley

Minimum Dimension

Dwell-,129

&OAeri

All"~

For Pedestrian Circulation

1.80 m

For Fire Lane

3.60 m

GvwtAen

D"allIrAq

On4-

um;t-

F

3.

'-4

6.

-4

74

3.

CCMPARISON OF PROPOSED DESIGN SOLUTIONS WITH THE MODOE APARTMENT COMPLEX

3.1

Comparison with Moroe Apartnents

3.2

The Decision Making Process

75

3.

COMPARISON OF PROPOSED DESIGN SOIDTIONS WITH THE MOROE APARIMENT COMPLEX

In this chapter, the process and product of this design proposal are described in

comparison with the case study.

Next, the decision making process is discussed in relation

to each stage of construction.

3.1

Comparison with Moroe Apartments

3.11

Proposed block plan

A)

All units are exposed to the sun.

B)

Each dwelling unit is equivalent in terms of amenities.

C)

This layout provides each facade with access articulation;

there are no

blank walls facing adjacent housing blocks.

3.12

Proposed Access

A)

The qualitative difference between the lower and upper units is minimized.

B)

Arrangement of the gardens and access provides a feeling of ownership to users.

C)

The proposed access variations can be one of the factors providing interest to

the townscape.

3.13

A)

Floor Plan

Arrangement of the support structure and infill unit allows tremendous variation

in

space organization.

B)

Minimum openings in the party walls make various configurations possible.

C)

Facade variations provide design accents to the elevation.

76

3.14

Open Space

A)

Every garden faces south.

B)

Each parking space is adjacent to its respective unit.

C) A common park is enclosed by the housing units and is controlled by the

housing conmunity.

In addition to the above description, an elaborated plan of Site Models 1 and 2 (Fig.20 -24

shows these variations in more detail.

77

I

-r1

q,

Pi

I1 I

I

2

0-

LOF

o

0

-04

K

LL

o Al

C%41I

I-

r-

4

H

I

0

a,

0

t%3

0

0

-a

0

I

I

L

z

EID

H4

1-A

I.e

I-A.

1-11

1L- 1

..

..

-F]

I

M2 LI

(

N

Street

Par ial Floor Plan of Site Model 1

P k

aa-aa

LJLLJ1

0

5

10

20 M

I

Street

I

I )amaI)

4JJP

kkIlI1IiL

lst Floor Plan

1st Floor Plan

Fig. 22

Fig. 22

80

Floor Plan of Site Model 1

o

5

10

20 M

2nd Floor Plan

Fig. 23

81

al Floor Plan of Site Model 1

a

a

S

*

I

a

I----------------------

*

,

*

s

a

,

'-a

i

a

a

I8

a*

a

a

I

S---------------------

0

5

10

20 M

3rd Floor Plan

Fig. 24

82

The Decision Making Process

3.2

Up to this point, this proposal has focused solely on the development of design

variations.

However, the decision making process is also a critical factor in developing

a housing plan.

The final product could vary greatly depending on the different policies

governing decision making.

Following are the components of a design decision:

Corponents

6)

1)

Support Structure

2)

7)

Entrance Type

Size of Dw~elling

subj ect to party

wall )

[11111 Liii

Primary Fa cade

L:

Elemant

2

8)

3)

location of Infill

location of an

Internal Staircase

Unit

4)

location of Wall,

Colums

5)

location of Duct

( Partitioning

Kitchen & Bath )

9)

Secondary F acade

Element

LI2ZLI

10 )

Garden/Fen ce

fd7

w

E

A.zz z

83

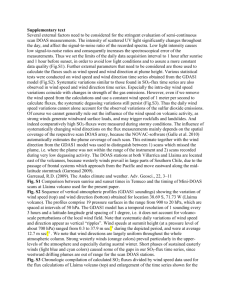

Next, the stage at which decisions are made qreatly influences the final product.

The following are the stages of decision making:

A)

design development (pre-construction)

B)

after completion of support structure (1-5)

C)

after decision concerning party wall (1-6)

D)

when user known but before occupancy

E)

during occupancy.

The following diagrams show the relationship between the components of the design decision and

the stages in which decisions can be/are made.

throughout the entire construction process.

Fig.2 5 shows that decisions can technically be made

Fig. 26 shows that decisions are usually made only during

the design development stage, which autamatically excludes tenant participation in major decisions.

Fig. 25 illustrates that at Stage D, tenants could technically be involved in decisions concerning

unit layout, access and facade variations, and use of open space.

From the tenant's point of view, the

ideal is to participate in decision making to the extent technically possible as in Fig. 25.

As seen in Fig.26, the extent of user participation in decisions for Japanese housing projects

such as Moroe Apartments is

usually limited to imput regarding furniture placement and garden main-

tenance.

Because of standarization of space elements through industrialization and mass production, the

tendency on the part of the Developer/Architect may be to allow these uniform components to dictate

a uniform design solution.

However, standardization can also permit tremendous variation while still

working within the framework of the contemporary construction process.

84

Fig. 25

Fig. 26

Design Issues and Respective Stage

Typical Decision Making Pattern for

at which User Could Technically Becone

Housing in Japan

Involved in the Decision Making Process

Elements

A

1)__

Stages

B

C

D

Elements

1)___

E

A

B

C

D

E

_

2)

2)

3)

3)

4)

4)

5)

Stages

__

_

_

_

5)

6)

6)__

7)

7)

8)

8)

9)

9)

10)

10)

_

_

_

_

__

_

_

_

_

_

_

_

_

_

* Stage at which tenants are currently

involved in decision-making

Stages at which decisions

can be made

LIZ

Stages at which no decisions

can be made

85

CONCLUSION

In this thesis, through use of a case study, the designer's comprehension for user needs is

analyzed, and a proposal for housing design responding to user requirements is studied. User requirements were manifested through reaction against a dwelling space which forced users to live a

uniform life style.

Also, basic but essential requirements for a dwelling environment are often

forgotten by designers who are historically unaccustamed to planning multi-tenant housing.

These

are the main problems in Japanese housing today.

Therefore, this study applies a methodical design process, using variable requirements as its

theme, to show that many alternatives can be provided at the level of the neighborhood as well as in

the individual dwelling unit.

It

is also intended to show what kind of choice can be provided at

different stages of the process developnent.

This makes possible a more flexible policy of decision-

making, taking into consideration important, more individual, user requirements that otherwise may be

neglected.

This thesis is based on the concepts of "support" and "urban tissue" as developed by SAR.

It

does not discuss technical issues, especially concerning infill units, which I intend to

study in

the future.

These concepts need not be applied to low-rise housing only;

I hope to

apply them to other types as well.

86

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Works in English

Habraken, N.J.

Variations:

.

The Systematic Design of Supports.

Massachusetts Institute of

Technology, MIT Laboratory of Architecture and Planning, 1976.

SAR '73:

SAR Method for the Developnent of Urban Environments.

Habraken, N.J.

Supports: An Alternative to Mass Housing.

.

1973.

Architectural Press, London and

Praeger, New York, 1971.

Turner, John F.C.

.

Housing by People:

Progress.

Toward Autonomty in Building Environments, Ideas in

Marion Bonans, Iondon, 1976.

Habraken, N.J.

.

Housing: "The Act of Dwelling", AJ. May 22, 1968.

Habraken, N.J.

.

"Involving People in the Housing Process", RIBA Journal.

Habraken, N.J. .

Transformations of the Site. Awater Press, 1982.

Hamdi, N. and Wilkinson, N. .

Rabeneck, Andrew.

Iondon, Noveiber, 1972.

"PSSHAK",

"The New PSSHAK", AD.

Alexander Christopher.

RIBA.

October, 1971.

October, 1975.

A Pattern Language.

Oxford University Press, New York, 1975.

87

Works in English (continued)

Alexander, Christopher.

The Tineless Way of Building, Oxford University Press, New York, 1979.

Alexander, Christopher.

The Oregon Experiment, Oxford University Press, New York,

Ryu, Yoshiko.

Alternative Housing Desiqn for Changinq Life Styles in Japan.

1975.

MIT M. Arch.

Thesis, 1982.

Seitz, Patricia.

Machi, Machinami, Machiya -- A Context for People's Place in Japan.

MIT M. Arch. Thesis, 1982.

Habraken, N.J. et al.

Grunsfeld Variations:

Tissue.

A Report on the Thematic Developmnt of an Urban

Department of Architecture, Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

88

Works in Japanese

Shimamura, Noboru et al. .

Suzuki, Kozin.

Toshi Design

Kyo no Machiya, Kajima Shuppan Kai, Tokyo,

Kindai Nihon no Kyoju Shuzoku, Kogyo Shuppan, Tokyo, 1980.

Kenkyu Tai.

Nihon no Toshi Kukan, Shokokusha, Tokyo, 1971.

"Modern Housing Prototypes", A-U Architecture and Urbanism.

Suzuki, Seibun.

Shugo Jutaku. Maruzen, Tokyo,

Tanaka, Ikko et al.

Suzuki, Seibun.

1971.

Japan Style.

Tokyo, 1975.

1970.

Kodansha, Tokyo, 1980.

Ju Yokyu no Tayoka ni Taio Shita Juko Keikaku ni Kansuru Kenkyu.

Japan Housing Corporation, Tokyo, 1975.

89