11, June, 1973

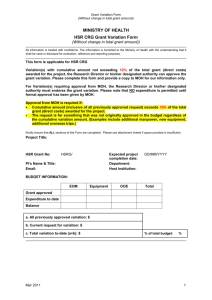

advertisement