EMPLOYER INVOLVEMENT IN THE WORKTRIP: NISSEN

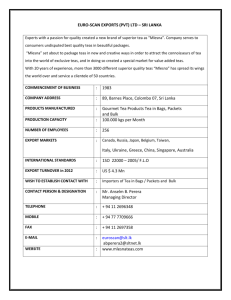

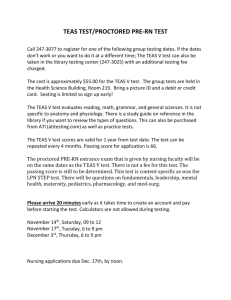

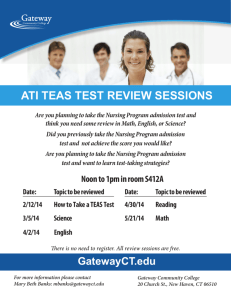

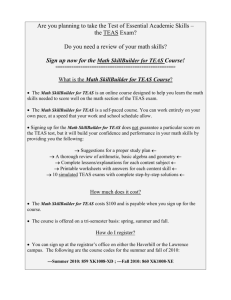

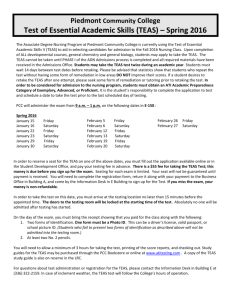

advertisement