Reform of the International Financial System and Institutions in Light

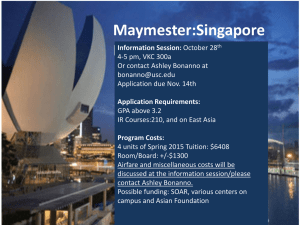

advertisement