Malaysia’s September 1998 Controls: Background, Context, Impacts, Comparisons, Implications, Lessons

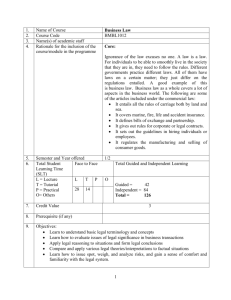

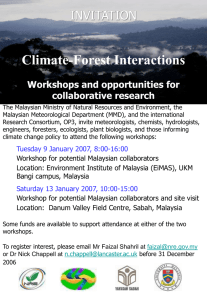

advertisement