UNITED NATIONS CONFERENCE ON TRADE AND DEVELOPMENT

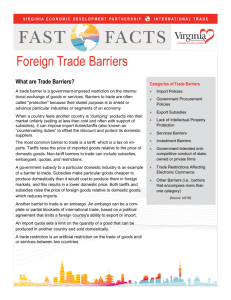

advertisement