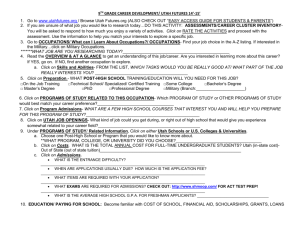

STATE PLANNING IN UTAH by IN MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE

advertisement