The Costs of a (Nearly) Fully Independent Board

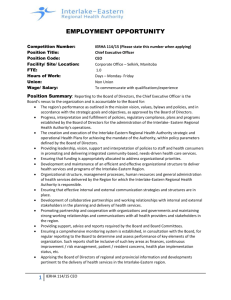

advertisement