Simultaneous Search in the Labor and Marriage Markets with

advertisement

Simultaneous Search in the Labor and Marriage Markets with

Endogenous Schooling Decisions∗

Luca Flabbi

UNC-Chapel Hill

CPC, IZA

Christopher Flinn

New York University

CCA

October 26, 2015

Very Preliminary and Incomplete

Abstract

Labor and marriage market decisions are joint decisions. If individuals are engaged

in a stable relationship, labor market decisions are taken at the household level. If

individuals are not yet engaged in a stable relationship, marriage market decisions

and opportunities are strongly influenced by the individual current and expected labor

market position. The literature recognizes the joint nature of these decision processes

but usually focuses only on one side of the decisions tree. Our analysis, instead,

develops and estimates a model designed to determine the joint equilibrium distribution

of labor market outcomes and marriage market statuses, together with an endogenous

schooling decision. The model is estimated by the Method of Simulated Moments using

labor market information from the Current Population Survey and marriage market

information from the American Community Survey.

Using the estimates of the model, we perform several comparative statics exercises.

On top of being of interest in themselves, they provide an empirical assessment of the

importance of taking into account the joint nature of the decision process in the two

markets. We also plan to use the parameter estimates to perform a series of policy

experiments comparing a labor income tax system based on individual taxation with

a system based on joint taxation.

JEL Codes: D13,J12,J64

∗

Sergio Ocampo and Mauricio Salazar Saenz provided excellent research assistantship. Partial funding

from the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) ESW grant RG-K1415 is gratefully acknowledged. The

views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and should not be attributed to the IDB.

1

1

Introduction

Labor and marriage market decisions are strongly interrelated. If individuals are engaged in

a stable relationship, labor market decisions are among the most important choices affecting

overall household welfare, and therefore are not taken in isolation but at the household level.

If individuals are not yet engaged in a stable relationship, marriage market decisions and

opportunities are strongly influenced by the individual’s current and expected labor market

position. The literature often recognizes the joint nature of these decision processes, but

usually focuses only on one side of the decisions tree.

With respect to the impact of the marriage market on labor market decisions, there

now exist a number of estimated models of household search1 that are able to examine the

impact of one spouse’s labor market status on the other spouse’s current and future labor

market choices. However, these contributions ignore the process leading to the formation

of the household and frequently lack intrahousehold behavior, since they typically impose

the existence of a household utility function.2

With respect to the impact of the labor market on marriage market decisions, there

exists a huge literature in economics, demography and population studies focusing on

how an individual’s current labor market state and future labor market performance may

impact outcomes in the marriage market. However, most of these contributions ignore

dynamic considerations and all of them consider labor market characteristics as a fixed

individual-level characteristic. In other words, these contributions ignore the fact that the

individual’s current labor market state may endogenously change as a result of marriage

market decisions.3

Our analysis utilizes an innovative methodological framework designed to determine

the joint equilibrium distribution of labor market outcomes and marriage market statuses.

1

See Dey and Flinn (2008); Gemici (2011); and Flabbi and Mabli (2012). Guler, Guvenen and Violante

(2012) do not estimate the household search model but provide an exhaustive theoretical discussion.

2

The notable exception is Gemici (2011) which includes some intrahousehold behavior and endogenous

marriage choices. However, intrahousehold behavior is mainly limited to the impact on the geographical

location decisions of the household and the marriage decisions are derived without imposing equilibrium

conditions on the marriage market.

3

Recent examples include DelBoca and Flinn (2014) which looks at married people but recognize that

marital sorting is influenced by labor market variables. However, these labor market variables are state

variables that cannot change as a result of the marriage. This is also the case in Chade and Ventura

(2005) which allows for endogenous household formation and dissolution (but not for wage dispersion.)

There also exists a rich literature on marriage sorting processes which exploits equilibrium conditions in the

marriage market (Pollack (1990); Dagsvik (2000); Choo and Siow (2006); and Choo (2015).) This setting

studies sorting over individual level characteristics which in principle may include labor market outcomes

but they are instead limited to demographic characteristics. Finally, the search and matching literature

with two-sided heterogeneity has been applied to study sorting in the marriage market (see for example

Shimer and Smith (2000)). Wong (2003) is an application estimating the model with the inclusion of labor

market variables (wages). However, wages are just one component of a single index describing individual

heterogeneity and they are permanent components, not allowed to change as a result of marriage market

dynamic.

2

Informed by the importance of human capital investments in both the marriage and labor

market, we also introduce an endogenous schooling choice which takes place before entering

both markets. Exploiting a number of simplifying assumptions, we are able to estimate the

model using cross-sectional wage distributions, unemployment durations, and transitions

across marriage market statuses taken from readily available and nationally representative

data sources. As a result, we can empirically assess the importance of taking into account

the joint nature of the decision process in the two markets and the cost of ignoring it when

using models for policy evaluation purposes.

We assume individuals begin adult life by making a schooling decision. After schooling is completed, individuals enter the marriage and labor market, jointly searching (in

continuous time) in both. Each market is characterized by frictions and by match-specific

shocks. Household interaction is assumed to be non-cooperative with each spouse making

job choices solely along the extensive margin, i.e., they decide to accept or reject an offer

if receiving one themselves and they decide to stay or quit their current job when their

spouse’s employment state changes. We solve the potential equilibrium multiplicity that

may arise in such a dual searcher setting by assuming that the spouse who is receiving the

offer is the first-mover, while the other spouse acts as a follower.

A few recent contributions introduce elements of interactions between the marriage

and labor markets. Jacquemet and Robin (2013) model endogenous household formation,

allowing for wage dispersion and a labor supply decision. However, only the labor supply

decision is endogenous and allowed to change with marriage market outcomes, while wages

are treated as a permanent individual-specific component. Greenwood, Guner, Kocharkov

and Santos (2015) develop a similar setting, adding, like us, an endogenous education

decision. However, the interaction with the labor market is even more limited than in

Jacquemet and Robin (2013), since only women are allowed to endogenously adjust labor

supply. Finally, Chiappori, Dias and Meghir (2015) allow for the same three choices we

consider in our model: schooling, marriage, and jobs. However, the interactions between

the labor and marriage market choices is more limited than in our case, since the marriage

decision is irrevocable and taken before entering the labor market. On the other hand, labor

market dynamics are allowed to possess a life-cycle pattern. These patterns are essentially

ruled out within our stationary setting.

After developing the model, we estimate it by the Method of Simulated Moments

(MSM) using labor market information from the Current Population Survey (CPS) and

marriage market information from the American Community Survey (ACS), under the

assumption that a monthly CPS sample is a point sample from the steady state distribution. With no on-the-job search in the labor market and no on-the-marriage search in the

marriage market, identifying the transition rate parameters associated with the labor and

marriage markets is reasonably straightforward, as are the wage offer distributions under

parametric (log normal) assumptions. The identification of the distribution of marriage

match values is more problematic, but it is solved by exploiting the rich combination of

“types”of couples arising in equilibrium. Types are described by combinations of school3

ing levels, labor market states, and wage levels when an individual is employed. Finally,

the distribution of schooling costs is the one on which we observe the least amount of

information and as a result we assume the distribution to be known up to one parameter.

Using the estimates of the model, we perform several comparative statics exercises.

In addition to being of direct interest in themselves, these exercises provide an empirical

assessment of the importance of taking into account the joint nature of the decision process

in the two markets. First, we explore the impact of changes in the labor market structure on

the joint equilibrium distribution of both markets. We analyze two changes: reducing labor

market frictions and eliminating gender differences in the wage offer distributions. Second,

we plan to estimate lifetime returns to schooling, showing the importance of both markets

in determining the final equilibrium outcomes. Some exercises will show how ignoring one

of the two markets, or ignoring the interaction between them, may impact the estimated

returns. Finally, we plan to assess the impact of changes in the marriage market structure,

such as recent demographic changes, on the joint equilibrium distribution of both markets

and on overall welfare.

As a final contribution, we plan to use the parameter estimates to perform a series of

policy experiments comparing a labor income tax system based on individual taxation with

a system based on joint taxation. Specifically, we will set a tax revenue objective, impose

alternative taxation schemes, and obtain the tax schedule necessary to satisfy the tax

revenue target under the two regimes. We will then obtain the joint equilibrium distribution

of schooling levels, labor market outcomes, and marriage market statuses under the two

regimes and compare their associate lifetime welfare levels.

The paper is organized as follows. Section 2 presents the model and section 3 the data.

Section 4 describes identification and econometric issues. Section 5 contains the preliminary

estimation results and section 6 the preliminary experiments results. No policy section is

included at the moment. Section 7 concludes.

2

Model

2.1

Environment

Individuals begin adult life by making a schooling decision, which involves a comparison

of the values of entering the labor and marriage markets with schooling type s ∈ {L, H},

denoting a low and high schooling level. The benefit of acquiring schooling is the access

to a schooling-specific labor market which is completely segregated from the labor market

of the other schooling level. The access to a schooling-specific labor market also has an

impact on marriage market opportunities. The cost of acquiring the high schooling level is

heterogeneous in the population and it is gender-specific. We denote gender with g ∈ {f, m}

and the cost of schooling with q ∼ Q(q|g).

After schooling is completed4 , individuals enter the marriage market and the labor

4

The timing implies that we ignore any time cost involved in the acquisition of schooling and any marriage

4

market. Each market is characterized by frictions and by match-specific shocks. In the

labor market, we denote the Poisson rate of arrival of job offers with λ (g, s) . A job offer

is fully characterized by a wage w ∼ F (w|g, s) . If a job is accepted and a match realized,

it is terminated by an exogenous shock η (g, s) . A job-match may also be endogenously

terminated as a result of changes in the marital status or a as a result of changes in the

labor market status of the other spouse. There is no on-the-job search in the current

version of the model.

Marriage markets are also characterized by frictions and offers arrive following a Poisson

process. Any member of one gender, no matter the education group, may meet and marry

a member of the other gender, no matter the education group. However, the probability of

meeting between and within schooling groups are allowed to be different and to be governed

by a CRS matching function Γ [S (g, s) , S (g 0 , s0 )] where S (g, s) denotes the measure of

single of gender g and schooling level s in the economy and the superscript 0 denotes the

other spouse variables. As a result, the Poisson arrival rate of a marriage opportunity to

an individual of gender g and schooling s with an individual of the opposite gender5 and

schooling s0 is:

Γ [S (g, s) , S (g 0 , s0 )]

λM g, s, s0 =

(1)

S (g, s)

A marriage offer is characterized by the gender, education level and labor market status

of each of the two spouses and by a match-specific utility of marriage denoted by θ ∼

G (θ). One individual of each gender is necessary to create a married couple. Only single

individuals are allowed to meet in the marriage market. Marriages can be terminated only

by an exogenous process with rate ηM .

Each single individual of gender g and educational level s has a utility function given

by:

u(l, c|g, s) = α (g) ln(l) + (1 − α (g)) ln(c)

(2)

where:

c = wh (g, s) + y

T

= l + h (g, s)

Consumption c is equal to the sum of labor income wh (g, s) and nonlabor income y. Time

T is allocated between leisure l and work but there is not intensive margin decision on

labor supply: h (g, s) is the gender and school-specific amount of hours required by each

job contract and individuals cannot choose it. An unemployed agent sets l = T , where T

is the upper bound on time available for leisure and work at any moment in time.

market or labor market activities happening during the schooling completion process. The schooling decision

is fixed after entering the labor and marriage markets.

5

Driven by data availability, we impose that marriage only happens between individuals of opposite sex.

5

Each married individual of gender g and educational level s married with an individual

of gender g 0 and educational level s0 has utility function given by:

u(l, c, θ|g, s, s0 ) = α (g) ln(l) + (1 − α (g)) ln(c) + θ

(3)

where:

c = wh (g, s) + w0 h g 0 , s0 + y + y 0

T

= l + h (g, s)

Consumption c is a public good and it is equal to the sum of both spouses labor and

nonlabor incomes. θ is another public good and by the utility of staying together. Time

T is allocated between the private good, leisure l and work, under the constraint mention

above that h (g, s) is not a choice variable but a job requirement. For the case in which a

spouse s is unemployed, then w = 0, and the same is true for spouse s0 .

Household interaction is assumed to be non-cooperative. Each spouse decides to accept

or reject a job offer and whether to keep or quit their current job. The spouse who is

receiving the offer is the first-mover, while the other spouse acts as a follower. This timing

convention solves the equilibrium multiplicity that may arise in the dual-searcher setting

we are analyzing. It may be justified by assuming that the spouse receiving the offer may

restrain from informing the other agent about the job offer unless it is optimal to do so.6

We assume that agents live forever and they they face a common instantaneous discount

rate, ρ.

2.2

Value Functions

The value function for an agent of gender g and schooling s, employed at wage w and

married to an agent with schooling s0 employed at wage w0 and enjoying a marriage flow

value of θ is:

ρ + η (g, s) + η g 0 , s0 + ηM V w, w0 , θ|g, s, s0 = u(l, c, θ|g, s, s0 )

(4)

0

0 0

0

+η (g, s) V 0, wR w , 0|g , s , s , θ|g, s, s

+η g 0 , s0 max V w, 0, θ|g, s, s0 , V 0, 0, θ|g, s, s0

+ηM max {V (w|g, s) , V (0|g, s)}

The value function is conditioned on the gender of the agent, their schooling, and the

schooling of the spouse, and it is function of wage of the agent (a wage of zero denotes

unemployment), the wage of the spouse, and marriage match-value. Given the state,

three shocks may hit the agent: an exogenous termination of her job at a rate η (g, s); an

6

When two single employed agent meet and decide to marry, it is not clear who should be considered

and who should be considered the follower conditioning on the criteria just described. In this case, we

randomize assuring a 50% chance to each gender.

6

exogenous termination of her spouse’s job at a rate η (g 0 , s0 ); and exogenous termination of

the marriage at a rate ηM . Notice that each spouse reacts optimally to a shock to the other

spouse’s labor market status, following the household interaction process described above.

We denote the optimal reaction (quitting or not quitting the current job) with the function

wR . For example wR (w0 , 0, θ|g 0 , s0 , s) in equation (4) assumes either value w0 if the spouse

keeps the current job after the agent has been exogenously terminated or value 0 if the

spouse quits the current job as a result of the agent’s change in labor market status. The

agent also reacts optimally to exogenous divorce, deciding whether to stay in the current

job or to quit in order to look for a better job offer. Notice we have introduced the notation

for value functions of single agents: they are just a function of the agent’s labor market

state.

The value function for an agent of gender g and schooling s, unemployed and married

to an agent with schooling s0 , working at job w0 and enjoying a marriage flow value of θ is:

ρ + λ (g, s) + η g 0 , s0 + ηM V 0, w0 , θ|g, s, s0 = u(T, c, θ|g, s, s0 )

(5)

Z

+λ (g, s) max V w, wR w0 , w, θ|g 0 , s0 , s , θ|g, s, s0 , V 0, w0 , θ|g, s, s0 dF (w|g, s)

+η g 0 , s0 V 0, 0, θ|g, s, s0

+ηM V (0|g, s)

Given the state, three shocks may hit the agent: a job offer at a rate λ (g, s), an exogenous

termination of her spouse’s job at a rate η (g 0 , s0 ), and an exogenous termination of the

marriage at a rate ηM . When the spouse’s job is terminated, no endogenous reaction follows

since agents are not allowed to divorce as a result of a change in labor market status. When

the agent receives a job offer, she will decide to accept or reject the job by maximizing over

the alternative value functions, anticipating the spouse’s optimal reaction. As before, we

denote the spouse’s optimal reaction with wR . If the marriage is terminated, no additional

actions are available.

The value function for an agent of gender g and schooling s, employed at wage w and

married to an agent with schooling s0 , searching for a job, and enjoying a marriage flow

value of θ is:

ρ + η (g, s) + λ g 0 , s0 + ηM V w, 0, θ|g, s, s0 = u(l, c, θ|g, s, s0 )

(6)

0

+η (g, s) V 0, 0, θ|g, s, s

Z

+λ g 0 , s0

V wR w, w0 , θ|g, s, s0 , w0 , θ|g, s, s0 dF w0 |g 0 , s0

A0 (w|g,s,s0 )

+ηM max {V (w|g, s) , V (0|g, s)}

where:

A0 w|g, s, s0 = w0 : V w0 , wR w, w0 , θ|g, s, s0 , θ|g, s, s0 > V 0, w, θ|g 0 , s0 , s

7

Given the state, three shocks may hit the agent: exogenous job termination at a rate

η (g, s), a job offer to her spouse at a rate λ (g 0 , s0 ), and exogenous termination of the

marriage at a rate ηM . When the job is terminated, no endogenous reaction follows since

agents are not allowed to divorce as a result of a change in labor market status. When the

spouse receives a job offer, she will decide whether to accept the job. If he accepts, the

agent in question will react optimally, as denoted by the reaction function wR . But not all

the job offers are acceptable to the spouse and in general the acceptance region depends on

the agent’s labor market state and type. We denote by A0 (w) the support of the job offers

distribution which is acceptable to the spouse given the agent’s job (w, h) . If the marriage

is terminated, the agent decides whether to continue employment at their current job or

to quit into unemployment so as to look for a better job.

The value function for an unemployed agent of gender g and schooling s, married to an

unemployed agent with schooling s0 , and enjoying a marriage flow value of θ is:

ρ + λ (g, s) + λ g 0 , s0 + ηM V 0, 0, θ|g, s, s0 = u(T, c, θ|g, s, s0 )

(7)

Z

+λ (g, s) max V w, 0, θ|g, s, s0 , V 0, 0, θ|g, s, s0 dF (w|g, s)

Z

0 0

+λ g , s

V 0, w0 , θ|g, s, s0 dF w0 |g 0 , s0

A0 (0|g,s,s0 )

+ηM V (0|g, s)

Given the state, three shocks may hit the agent: an exogenous job offer at a rate λ (g, s), a

job offer to the spouse at a rate λ (g 0 , s0 ), and exogenous termination of the marriage at a

rate ηM . When the agent receives the offer, she is the first mover and decides whether to

accept the offer. When the spouse receives the offer, the spouse decides whether to accept

the offer. In both cases, the other spouse has no ability to respond. If the marriage is

terminated, the agent is back to the single unemployed state.

The value function for an unemployed single agent of gender g and schooling s is:

[ρ + λ (g, s) + λM (g, s, L) + λM (g, s, H)] V (0|g, s) = u(T, c|g, s)

Z

+λ (g, s) max {V (w|g, s) , V (0|g, s)} dF (w|g, s)

X

+

λM g, s, s0 ×

s0 ∈{L,H}

U (g 0 , s0 )

max {V (0, 0, θ|g, s, s0 ) , V (0|g, s)} dG (θ) +

0 0

B(0,0|g

R

R ,s ,s)

0

0

max {V (0, wR (w0 , 0, θ|g 0 , s0 , s) , θ|g, s, s0 ) , V (0|g, s)}

E (g , s )

0

0

0

0

0

C(g ,s ) B(w ,0|g ,s ,s)

0

0

0

0

0

0

dG (θ) dF (w |g , s , w ∈ C (g , s ))

R

8

(8)

where:

B w, w0 |g, s, s0

≡

θ : V wR w, w0 , θ|g, s, s0 , wR w0 , w, θ|g 0 , s0 , s , θ|g, s, s0 > V (w|g, s)

C (g, s) ≡ {w : V (w|g, s) > V (0|g, s)}

Given the state, two shocks may hit the agent: a job offer at a rate λ (g, s) and a

marriage offer at a rate λM (g, s, L) if coming from a low schooling-level individual or at

a rate λM (g, s, H) if coming from a high schooling-level individual. Given the schooling

level, the potential spouse can be unemployed or employed: we denote the endogenous

measures of these two sets in equilibrium with U (g 0 , s0 ) and E (g 0 , s0 ) . The set of employed

singles is drawn only from the accepted wage distribution of this type, which has support

C (g 0 , s0 ). The set B (w, w0 |g, s, s0 ) takes into account the fact that marriage is consensual

and the current agent can decide about marrying a potential spouse only if the potential

spouse also agrees to marry.

The value function for a single agent of gender g and schooling s, employed at wage w

is:

[ρ + η (g, s) + λM (g, s, L) + λM (g, s, H)] V (w|g, s) = u(l, c|g, s)

(9)

+η (g, s) V (0|g, s)

X

+

λM g, s, s0 ×

s0 ∈{L,H}

U (g 0 , s0 )

max {V (wR (w, 0, θ|g, s, s0 ) , 0, θ|g, s, s0 ) , V (w|g, s)} dG (θ) +

0 0

B(0,w|g

R

R ,s ,s)

0

0

E (g , s )

max {V (wR (w, w0 , θ|g, s, s0 ) , wR (w0 , w, θ|g 0 , s0 , s) , θ|g, s, s0 ) , V (w|g, s)}

C(g 0 ,s0 ) B(w0 ,w|g 0 ,s0 ,s)

0

0

0

0

0

0

dG (θ) dF (w |g , s , w ∈ C (g , s ))

R

Given the state, two shocks may hit the agent: an exogenous job termination at a rate

η (g, s) and a marriage offer at a rate λM (g, s, L) if coming from a low schooling-level

individual or at a rate λM (g, s, H) if coming from a high schooling-level individual. As

before, meeting in the marriage market may be with singles of any schooling level who can

be employed or unemployed. And as before, each agent reacts optimally with respect to her

labor market decision when considering marriage. However, now there is the possibility

that two single employed agents meet in the marriage market, generating an ambiguity

about which one of the two is the leader in the game. In the notation, above we are

assuming that the agent for whom we are writing the value function is the leader. In

simulation and estimation, we randomize which one of the two agents is the leader when

meetings of two employed singles occur.

9

2.3

2.3.1

Equilibrium

Definition

The optimal decision rules have a reservation value property. In the labor market the

reservation value is defined over the wage w; in the marriage market over the marriage

match value θ; and the schooling reservation value is defined with respect to the schooling

cost q.

First, we look at labor market decisions. When single, decision rules are identical

to a standard single agent search model and the reservation wage above which offers are

accepted is defined as:

w∗ (g, s) : V (w∗ |g, s) = V (0|g, s)

(10)

When married, labor market decision rules also depend on the labor market status of the

spouse, due to the nonlinearity of the utility function.7 As a result, the reservation wage

of an individual with schooling s, married to a spouse with schooling s0 and labor market

status characterized by w08 , in a marriage generating a match value θ is given by:

w∗ w0 , θ|g, s, s0 :

(11)

∗

0

∗

0 0

0

0

V w , wR w , w , θ|g , s , s , θ|g, s = V 0, w , θ|g, s, s

Next, we consider marriage market decisions. Again, given the assumptions on the

utility function, the two markets are interdependent and the marriage market decision

depends on the labor market status of both the agent and the potential spouse. The

reservation match value for the marriage to occur (from this agent’s perspective) is:

(12)

θ∗ w, w0 |g, s, s0 :

∗

0

∗ 0 0

0 ∗

0

V wR w, w , θ |g, s, s , wR w , w, θ |g , s , s , θ |g, s = V (w|g, s)

Finally, we look at schooling decisions. Schooling decisions have a different timing than

labor market and marriage market decisions because they are taken before entering the two

markets. Once a schooling decision is made, it cannot be changed and the individual enters

simultanously the marriage and labor market as a single unemployed agent of schooling

level s. As a result, the reservation cost of acquiring the high level of schooling H is given

by:

q ∗ (g) :

(13)

∗

V (0|g, H) − q = V (0|g, L)

where individuals with cost less than or equal to q ∗ (g) acquire schooling level H.

We can now propose the following:

7

See Dey and Flinn (2008). A systematic treatment of the issue is also provided by Guler, Guvenen and

Violante (2012), while Flabbi and Mabli (2012) exploit the result in estimation.

8

Recall that w0 > 0 defines employement and w0 = 0 defines unemployment.

10

Definition 1 Given g ∈ {f, m}, s ∈ {L, H}, s0 ∈ {L, H} and:

α (g)

λM (g, s, s0 )

λ (g, s)

ρ

ηM

η (g, s) ,

, Q(q|g)

,

h(g, s)

G(θ)

F (w|g, s)

an equilibrium is a set of values

V ., ., θ|g, s, s0 , V (.|g, s)

that solves equations (4)-(9) under the optimal decisions rules characterized by equations

(10)-(13).

2.3.2

Computational Method

A closed form solution for the value function characterized in Definition 1 is not available

and therefore we use simulation methods to solve for an equilibrium at given parameter

values.

The model is solved by evaluating the value functions in a discretized grid of wages and

marriage match-specific values, given the set of parameter values and the model’s steady

state equilibrium conditions. The model’s steady state equilibrium conditions are particularly challenging in our context since the equilibrium distribution of singles is endogenous

and it is necessary to compute the value functions. Notice that we have to keep track not

only of the proportion of singles but also of their equilibrium distribution over labor market states (including over accepted wages while employed) and schooling levels since the

labor market state and schooling level of single agents has an impact on marriage market

decisions.

The procedure works as follow. Given a set of parameters and a guess of the relevant

steady state equilibrium distribution, a first set of value functions is found by solving the

fixed point problem. The fixed point problem is over a quite a high-dimensional vector of

values since we have to jointly iterate over value functions in the marriage market and the

labor market for each value of the discretized wage and value of marriage grids, and for

each gender and education level. The fixed point over the value functions for given steady

state equilibrium distribution constitutes the “inner loop” of our simulation procedure.

Given the value functions, we can obtain an updated value of the steady state equilibrium

distribution that can be compared with the starting distribution and, in case of lack of

convergence, can be used to find a new set of value functions. The computation of the

steady state equilibrium distribution for given value function constitutes the “outer loop”

of our simulation procedure. The process is iterated until convergence is reached using

usual tolerance criteria.

Given this general structure, additional details of the simulation procedure need to be

solved. First, we have to decide whether to jointly simulate both sides of the marriage

11

market or whether to directly utilize the steady state distributions. In order to reduce the

computational burden, we chose the second alternative. As a result, when a marriage offer

is received by a given individual of gender g, a potential spouse is drawn from the steady

state distribution of single agents of gender g 0 .

Second, our leader-follower approach cannot solve the issue of two single employed

agents meeting in the marriage market. In this particular case, we choose the randomization

implemented by some previous papers in this literature: when the agent is single-employed

and another single-employed agent is drawn as a potential spouse, the leader of the marriage

game is chosen randomly assigning a 0.5 probablity to each agent to be the leader.

Third, the simulation is done agent by agent, storing each agent’s state. The state of

an agent is determined by her schooling level, wage and marriage status. If the agent is

married, the spouse’s schooling level and wage and the couple’s match-specific marriage

utility are also stored. Mirroring the data we will use in estimation, we store each agent’s

state every three months.

Finally, the steady state used in the “outer loop” is computed using the final 30% of the

total number of periods simulated. A total of 5,000 agents of each type (gender-schooling)

are simulated for 540 months.

2.3.3

Discussion

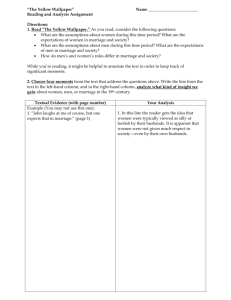

A graphical representation of the equilibrium outcomes both in the marriage and in the

labor market is reported in Figures 1 through 3.

We first focus on labor market decisions. When an agent is single and unemployed,

or in a couple with both spouses unemployed, the employment decision is characterized

by the usual reservation wage policy rule. When an unemployed agent is married to an

employed agent, the employment decision is more complex since it depends on the wage

and schooling level of the spouse. In this situation, when the unemployed spouse receives

an offer, three outcomes are possible: the agent can reject the job offer, the agent can

accept his job offer and the spouse quit her current job, or the agent can accept his job

offer and the spouse keep her current job. Figure 1 shows the solution to this game: the

wife is employed at one of the wages reported on the x-axis and the husband is receiving a

job at one of the wages reported on the y-axis. Each panel represents one of the possible

schooling combinations. The darkest area at the bottom of each panel shows the region in

which the offer is rejected; the most lightly-shaded region is where both agents keep their

jobs; the remaining middle gray area to the left of each panel shows the region where the

agent accepts the offer and the spouse quits her job. As expected, this area corresponds to a

combination of relatively low spouse’s wages and relatively high wage offers. Similarly, the

darkest area corresponds to combinations of low wage offers and high spouse wages. Only

when the husband receives a relatively high wage offer and the wife is already employed at

a job paying a relatively high wage, will they both be employed in equilibrium.

Next, we look at marriage market decisions. When two unemployed agents meet, the

12

marriage decision depends only on the match draw θ and, for a given schooling level

combination, there will exist a unique reservation θ∗ above which the agents decide to

marry. The marriage decision when two employed agents meet is more complicated because

each θ draw is defining an acceptance region over the space of the couples’ accepted wages.

Figure 2 represents such region for a given θ value. The equilibrium is characterized by

four regions: the darkest area (with wages below the reservation values and therefore

never active) indicates non-marriage; the lightest area indicates marriage with both agents

keeping their current job; the second darkest (next to the vertical axis) indicates marriage

and quitting of the current job by the man; and the second lightest (next to the horizontal

axis) indicates marriage and quitting by the woman. Note that, similarly to what happened

in Figure 1, quitting is induced when one wage is relatively low when compared to the other.

As a result, we observe married couples with both agents employed only when they both

have relatively high wages.

Figure 3 displays the joint distributions of wages for a married couple where both

spouses are employed, conditioning on the four schooling levels combinations. The joint

distributions show the assortative mating in wage levels implied by the equilibrium behavior

we have shown in Figure 1 and 2. Figure 3 also shows how both markets, combined

with the spouses’ schooling levels, have a genuinely joint impact on the four equilibrium

distributions.

3

Data

We use the Current Population Survey (CPS) to extract moments referring to: proportion

across labor market states, unemployment durations, means and standard deviations of

accepted wages, and correlations between spouses accepted wages. We use the American

Community Survey (ACS) to extract moments referring to proportions of the population

in the various marriage market states and transitions between marriage market states over

time. All the moments are computed by gender and schooling level.

We impose the following restrictions on the sample:

• Age: 25-49;

• Education:

– High level of schooling: College completion or more;

– Low level of schooling: Associate degree, some college, HS completed or less;

• Race: White;

• Year: 2007.

13

The states in the two markets are defined as follows. Married individuals are individuals

who declare that they are currently married. We classify all the individuals who are

not married as single, including those cohabiting. Employed individuals are individuals

currently working. All the other individuals are considered searching in the labor market,

even if they declare to be out of the labor force.

4

Econometric Issues

The identification of the model requires a set of additional functional form assumptions. As

shown by Flinn and Heckman (1982), we need to assume recoverable wage offer distributions

if we want to identify them from accepted wages information. We assume the wage offers

distributions to be lognormal with gender- and schooling-specific parameters µ (g, s) and

σ (g, s).

The marriage match-specific value θ is unobservable but the equilibrium shows it has

an impact on the “type” of marriage that is realized,9 where type is defined by the labor

market state and schooling level of the spouses. We assume a normal distribution with

parameters µθ and σθ .

The cost of acquiring the high schooling level with respect to the low schooling level

has only an impact on the schooling level acquired before entering the marriage and labor market. This simple threshold-crossing impact forces us to assume a one-parameter

distribution. We assume a negative exponential but with gender-specific parameters τ (g).

Finally, we need to impose a functional form for the contact rate functions. Since we

can observe gender and schooling specific transitions, we can identify marriage market

meeting rates that are gender-specific and schooling-specific in both spouses’ schooling. As

a result we can identify a two-parameter matching function which we will assume has the

following frequently used Cobb-Douglas specification:

0

0

Γ S (g, s) , S g 0 , s0 = β s, s0 S (g, s)ν(s,s ) S (g, s)(1−ν(s,s ))

(14)

The estimation procedure involves three main steps. First, we fix the following parameters:

Θ1 = {ρ, T, h (g, s)}g∈{f,m},s∈{L,H}

(15)

The discount rate is fixed to 5% a year, the time endowment to 80, and the job hours

requirements to the mean of each specific gender-schooling group.

Second, we use the Method of Simulated Moments (MSM) to estimate the following

set of parameters:

0)

λ

(g,

s)

λ

(g,

s,

s

M

η (g, s)

ηM

Θ2 =

,

, α (g)

(16)

µ (g, s)

µθ

σ (g, s)

σθ

g∈{f,m},s∈{L,H},s0 ∈{L,H}

9

See in particular Figure 2.

14

where the first column refers to labor market parameters, the second to marriage market

parameters, and the third to the utility function parameter.

Third, we recover the following set of parameters:

Θ3 = τ (g) , β s, s0 , ν s, s0 g∈{f,m},s∈{L,H},s0 ∈{L,H}

by solving identities (1) and by inverting the identity equating the observed proportion in

the high schooling-level group with the equilibrium proportion implied by the model.

5

Preliminary Estimation Results

Preliminary point estimates from the estimation procedure are presented in Table 2. The

first row reports the estimate of the preference parameter α: the weight on leisure in the

log-linear utility function we assume (see equations 2 and 3.) We estimate a value quite

similar to previous existing work but, contrary to previous literature, we find it to be

slightly higher for men than women.

The second group of parameters describes the labor market structure for each gender

and schooling level. The mobility parameters are estimated to be similar to previous

empirical work using a comparable setting. The location and scale parameters of the

lognormal wage offers distribution imply a gender differential in average wage offers of

about 6% in the low schooling group and of about 4% in the high schooling group. The

returns to acquiring a high level of schooling in terms of mean wages offers is about 39%

for women and about 37% for men. Both results are derived by computing the average

wage offers conditional on gender and schooling at our estimated parameters. Means and

variances of wage offers for the four groups are reported in the top two rows of Table 3.

The third group of parameters describes the marriage market structure for each gender

and schooling level. The arrival rate of marriage offers λM follows the expected ranking,

with offers more likely to arrive from individuals with the same schooling level. However,

they are estimated to be extremely low, predicting that the average duration for receiving

a marriage offer is about 26 years. We are currently working to improve the performance

of the estimated model along this dimension. The location and scale parameters of the

marriage match value distribution predict an expected value of about 0.307 (see Table 3.)

Given that θ is additively separable in the flow utility where leisure and consumption enter

in logs and since the estimated variance is fairly low, we can infer that the marriage match

value plays a significant but not major role in the marriage decision for the average couple.

Tables 4 to 6 present some measures of model fit. Table 4 reports a major labor market

outcome: accepted wages. The fit is reasonable on the first moments for all groups but it

is not on the standard deviations of the high schooling group, both in the male and female

samples. We are currently working to improve the performance of the estimated model

along this dimension. Table 5 reports the joint steady state proportions over labor market

state, marriage market status, schooling level and gender. The average fit is good but

15

there is one particular feature we systematically over-estimate: the proportion of couples

with one spouse working and the other spouse unemployed. This is another dimension

we are currently working on to improve the fit. We suspect it may require some changes

in our behavioral model. Finally, Table 6 presents fits over transitions between marriage

and labor market states. We fit some moments quite well while others less so, even if we

always manage to produce estimates of the right order of magnitude (a weak argument,

we realize).

6

Preliminary Experimental Results

In this preliminary version, we present just two comparative statics exercises. The first,

reported in Table 7, looks at the impact of decreasing labor market frictions in the market

for the high level of schooling. Since the value of participation in such a market is increasing (less frictions mean better labor market opportunities) we expect the proportion

of individuals acquiring a college degree to increase. This is exactly what we observe in

the two bottom rows of Table 7. When the arrival rate of offers double, the proportion of

women acquiring the high level of schooling increases by about 18%, and the proportion of

men increases by about 20%. We also observe a small increase in the proportion of married people. It results from the fact that more individuals have a high level of schooling

(a desirable characteristics in the marriage market, too) and that those who do also have

better labor market opportunities (because of the lower level of frictions). Even if limited in magnitude, this type of effect shows how even a minor change in the labor market

structure gets transferred to marriage market outcomes.

The second comparative statics exercise is reported in Table 8. The experiment consists

in setting the female labor market structure (arrival and termination rates; wage offers at

each schooling level) equal to the estimated male labor market structure. The motivation

rests on the gender differential literature and it indicates how gender asymmetries in labor

market structure impact gender differences in marriage rates and schooling rates. A first

result concerns schooling decisions: women acquire less education than at baseline. This

is due to the fact that low schooling labor market parameters for men are relatively better

than those for women. A second result relates to labor market outcomes: the gender gap

on them essentially disappears. Still, this is informative because it indicates that gender

asymmetries in the marriage market do not negatively impact women’s labor market performance. Finally, the third result is directly informative about the joint decision process in

the two markets. Despite a large change in women’s labor market parameters, the marriage

rate barely changes, moving from 52.45% to 52.43%.

16

7

Conclusion

The paper presents a tractable framework to analyze simultaneous search in the labor and

marriage markets in the presence of endogenous schooling decisions. After developing the

model, we propose an identification and estimation strategy of its structural parameters.

We implement it using data from the Current Population Survey (CPS) to describe the

labor market dynamic and from the American Community Survey (ACS) to describe the

marriage market dynamic. Preliminary results generate reasonable point estimates and a

good fit along numerous dimensions. However, we still consider them preliminary because

they are not able to reproduce two data features we judge crucially important: variance of

accepted wages for the high schooling groups and the proportion of married couples where

one spouse works and the other is unemployed.

We also provide a set of preliminary comparative statics exercises showing the magnitude of the interactions between the two markets. We plan to implement a larger set of

comparative statics exercises in order to provide an empirical assessment of the importance

of taking into account the joint nature of the decision process in the two markets. Finally,

we plan to use the parameter estimates to perform a series of policy experiments comparing a labor income tax system based on individual taxation with a system based on joint

taxation.

17

References

Chade, H. and Ventura, G. (2005), ‘Income taxation and marital decisions’, Review of

Economic Dynamics 8, 565–599.

Chiappori, P.-A., Dias, M. C. and Meghir, C. (2015), The Marriage Market, Labor Supply and Education Choice, Working Paper 21004, National Bureau of Economic

Research.

Choo, E. (2015), ‘Dynamic marriage matching: an empirical framework.’, Econometrica

83(4), 1373–1423.

Choo, E. and Siow, A. (2006), ‘Who marries whom and why’, Journal of Political Economy

114(1).

Dagsvik, J. (2000), ‘Aggregation in matching markets.’, International Economic Review

41(27- 57).

DelBoca, D. and Flinn, C. (2014), ‘Household behavior and the marriage market’, Journal

of Economic Theory 150, 515–550.

Dey, M. and Flinn, C. (2008), ‘Household Search and Health Insurance Coverage’, Journal

of Econometrics 145, 43–63.

Flabbi, L. and Mabli, J. (2012), ‘Household Search or Individual Search: Does it Matter?

Evidence from Lifetime Inequality Estimates’, IZA Discussion Paper 6908.

Gemici, A. (2011), ‘Family migration and labor market outcomes’, mimeo .

Greenwood, J., Guner, N., Kocharkov, G. and Santos, C. (2015), ‘Technology and the

changing family: A unified model of marriage, divorce, educational attainment, and

married female labor-force participation’, AEJ: Macroeconomics p. Forthcoming.

Guler, B., Guvenen, F. and Violante, G. (2012), ‘Joint-Search Theory: New Opportunities

and New Frictions’, Journal of Monetary Economics 59(4), 352–369.

Jacquemet, N. and Robin, J.-M. (2013), Assortative matching and search with labor supply

and home production, CeMMAP working papers CWP07/13, Centre for Microdata

Methods and Practice, Institute for Fiscal Studies.

Pollack, R. (1990), ‘Two-sex demographic models’, Journal of Political Economy 98, 399–

420.

Shimer, R. and Smith, L. (2000), ‘Assortative matching and search’, Econometrica

68(2), 343–369.

Wong, L. Y. (2003), ‘Structural estimation of marriage models’, Journal of Labor Economics 21(3), pp. 699–727.

18

Table 1: Descriptive Statistics CPS Sample

Gender:

Education:

Low

Female

High

Tot

Low

Male

High

Tot

32.8

31.2

26.7

4.4

63.9

16.2

19.9

7.1

12.8

36.1

48.9

51.1

33.8

17.2

100.0

37.5

32.4

25.6

6.8

69.9

13.6

16.5

4.2

12.3

30.1

51.1

48.9

29.8

19.1

100.0

3.3

60.6

63.9

0.8

35.3

36.1

4.1

95.9

100.0

3.7

66.2

69.9

0.7

29.4

30.1

4.4

95.6

100.0

13.4

5.8

23.2

11.2

16.2

7.4

26.3

13.5

4.2

5.5

4.3

5.2

3.9

4.9

3.2

4.2

31,565

17,828

36,056

15,521

Marriage Market:

Single

Married

with Low

with High

Total

Labor Market:

Unemployed

Employed

Total

Wages:

Mean

SD

U Durations:

Mean

SD

N. Observations

19

49,393

51,577

Table 2: MSM Estimated Parameters

Gender (g):

Schooling (s):

α (g)

Female

Low

High

Male

Low

High

0.167

0.174

λ (g, s)

η (g, s)

µ (g, s)

σ (g, s)

0.320

0.022

2.445

0.423

0.370

0.015

2.980

0.309

0.352

0.020

2.483

0.468

0.446

0.019

3.009

0.337

λM (g, s, L0 )

λM (g, s, H 0 )

ηM

µθ

σθ

0.0031

0.0020

0.0021 0.0028

0.0031 0.0020

0.009

0.307

0.465

0.0020

0.0039

20

Table 3: Exogenous Heterogeneity implied by MSM Estimates

Gender (g):

Schooling (s):

Female

Low High

Male

Low High

Wage Offers:

E (w|g, s)

V (w|g, s)

12.61

31.14

13.36

43.66

20.64

42.61

Marriage Match Values:

E (θ)

V (θ)

Cost of Schooling:

E (q|s)

233.9

21

21.45

55.18

0.307

0.217

299.4

Table 4: Model Fit: Accepted Wages

Gender (g):

Schooling (s):

Female

Low High

Male

Low High

15.18

16.50

23.55

25.69

16.52

18.45

24.26

27.25

5.26

5.19

6.22

6.18

6.63

6.75

6.81

7.02

13.40

14.12

23.16

23.87

16.18

19.12

26.34

30.12

5.83

6.01

11.16

11.25

7.41

7.91

13.51

13.82

Estimated:

Mean

Single

Married

SD

Single

Married

Sample:

Mean

Single

Married

SD

Single

Married

22

Table 5: Model Fit: Steady State Proportions (%)

Gender (g):

Schooling (s):

Low

Female

High Total

Low

Male

High Total

Estimated:

Single:

U

E

30.1

3.0

27.1

16.9

0.9

16.0

46.9

3.9

43.1

34.3

2.8

31.5

13.8

0.7

13.1

48.1

3.5

44.7

Married:

UU

UE

EU

EE

29.3

0.4

5.6

2.9

20.6

23.7

0.2

1.8

5.2

16.6

53.1

0.5

7.3

8.0

37.2

31.0

0.3

5.9

3.2

21.5

20.9

0.2

1.9

3.9

14.8

51.9

0.5

7.9

7.2

36.3

Total

59.4

40.6

100.0

65.3

34.7

100.0

Single:

U

E

32.8

2.2

30.6

16.2

0.4

15.7

48.9

2.6

46.3

37.5

2.7

34.8

13.6

0.5

13.1

51.1

3.1

48.0

Married:

UU

UE

EU

EE

31.2

0.2

1.0

0.9

29.1

19.9

0.0

0.4

0.3

19.3

51.1

0.2

1.4

1.1

48.4

32.4

0.2

0.9

1.0

30.4

16.5

0.0

0.2

0.3

15.9

48.9

0.2

1.1

1.3

46.4

Total

63.9

36.1

100.0

69.9

30.1

100.0

Sample:

23

Table 6: Model Fit: Transitions (%)

Single

SL

SH

MLL

Married

MLH MHL

Total

MHH

Estimated:

Males:

SL

SH

ML

MH

91.1

0.0

6.8

0.0

0.0

85.9

0.0

4.5

5.5

0.0

55.2

0.1

3.3

0.0

37.9

0.0

0.0

6.9

0.0

46.6

0.0

7.2

0.0

48.8

100.0

100.0

100.0

100.0

Females:

SL

SH

ML

MH

90.3

0.0

5.7

0.0

0.0

87.3

0.0

4.3

6.3

0.0

60.7

0.1

3.4

0.0

33.6

0.1

0.0

6.6

0.1

51.8

0.0

6.1

0.1

43.7

100.0

100.0

100.0

100.0

Males:

SL

SH

ML

MH

95.3

0.0

3.8

0.0

0.0

92.3

0.0

2.1

3.3

0.0

73.7

0.0

1.3

0.0

22.5

0.0

0.0

1.6

0.0

24.4

0.0

6.1

0.0

73.4

100.0

100.0

100.0

100.0

Females:

SL

SH

ML

MH

95.0

0.0

4.3

0.0

0.0

91.9

0.0

2.5

4.2

0.0

81.2

0.0

0.8

0.0

14.5

0.0

0.0

2.9

0.0

35.3

0.0

5.3

0.0

62.2

100.0

100.0

100.0

100.0

Sample:

24

Table 7: Experiments: Reducing Labor Market Frictions for Schooling Level H

Baseline

Increase in λ (g, H)

10%

50% 100%

Labor and Marriage Mkts. Proportions:

Single

U

E

47.55

3.66

43.89

47.45

3.50

43.95

47.34

3.61

43.73

47.26

3.51

43.75

Married

UU

UE

EU

EE

52.45

0.49

7.62

7.62

36.72

52.55

0.53

7.53

7.53

36.96

52.66

0.50

7.76

7.76

36.63

52.74

0.45

7.89

7.89

36.50

37.27

31.31

40.99

34.75

43.91

37.55

Proportion H Schooling:

Female

Male

36.10

30.10

25

Table 8: Eliminating Gender Differences in Labor Market Structure

Baseline

Female Male

Experiment

Female Male

Schooling:

Proportion H

36.10

30.10

32.26

30.03

24.25

27.25

16.52

18.45

25.42

27.47

16.39

18.10

24.26

27.46

16.41

18.89

Labor and Marriage Markets:

Wages:

Single E (w|g, H, E)

Married E (w|g, H, E)

Single E (w|g, L, E)

Married E (w|g, L, E)

23.55

25.69

15.18

16.50

Proportions:

Single

U

E

47.55

3.66

43.89

47.57

3.55

44.02

Married

UU

UE

EU

EE

52.45

0.49

7.62

7.62

36.72

52.43

0.44

8.36

8.36

35.28

Note: The experiment consists in setting the female labor market structure (arrival and termination

rates and wage offers) equal to the estimated male labor market structure.

26

Figure 1: Job Offer to Married UE couples - Husband leads

Emp. Decision MUE−LL − T 1

Emp. Decision MUE−LH − T 1

100

2

80

80

60

60

Wage

Wage

100

40

3

20

0

40

3

20

1

0

2

20

40

60

Wife Wage

80

0

100

1

0

20

Emp. Decision MUE−HL − T 1

2

80

80

60

60

40

3

20

0

20

40

60

Wife Wage

80

100

2

40

3

20

1

0

80

Emp. Decision MUE−HH − T 1

100

Wage

Wage

100

40

60

Wife Wage

0

100

27

1

0

20

40

60

Wife Wage

80

100

Figure 2: Marriage Offer between two Employed - Husband leads

M Lead LS−HS − T 3

100

80

80

Woman Wage

Woman Wage

M Lead LS−LS − T 3

100

60

40

20

0

60

40

20

0

20

40

60

Man Wage

80

0

100

0

20

100

80

80

60

40

20

0

80

100

80

100

M Lead HS−HS − T 3

100

Woman Wage

Woman Wage

M Lead HS−LS − T 3

40

60

Man Wage

60

40

20

0

20

40

60

Man Wage

80

0

100

28

0

20

40

60

Man Wage

Figure 3: Joint Accepted Wages distribution - Married couple

MEE LH

MEE LL

6000

1000

4000

500

2000

0

0

0

0

0

50

wW

100

100

0

50

50

wW

wM

50

100

MEE HL

1000

2000

500

0

0

0

0

wW

0

100

0

50

50

100

wM

MEE HH

4000

50

100

wW

wM

29

50

100

100

wM