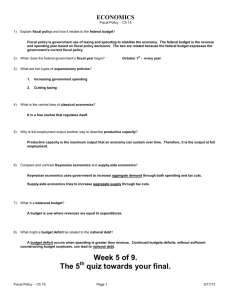

T P S B

advertisement