Country presentation by T H

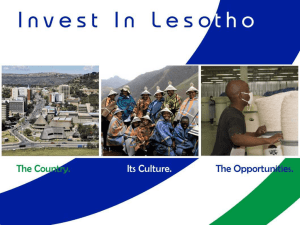

advertisement