Louise Street-Muscato for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in... presented on April 28, 1997. Title: Evaluating Oregon's Minors and...

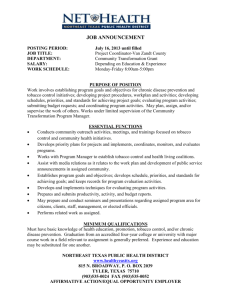

advertisement