by Denise Tan B.A., Economics, 2001 University of California at Berkeley

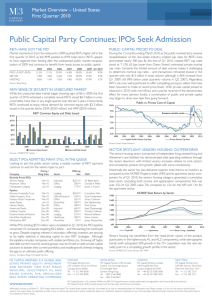

advertisement