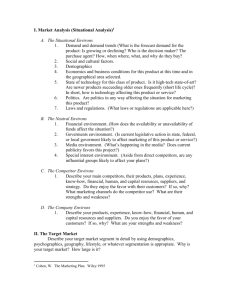

Developing For Demand- An Analysis of Demand Segmentation Methods and

advertisement