EVOLUTION Jim Zien SCIENCE IN

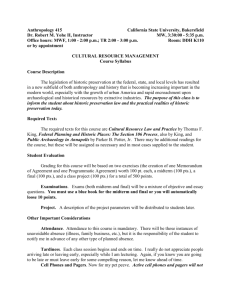

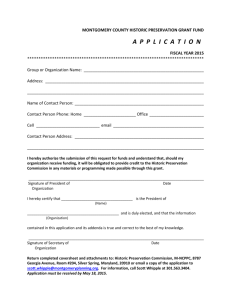

advertisement