1976

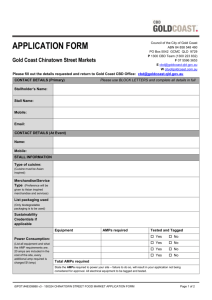

advertisement