PROMOTING HOMEOWNERSHIP Wilbur III Submitted in Partial Fulfillment

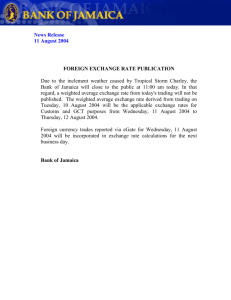

advertisement