Curriculum Planning for Black Public Education C.

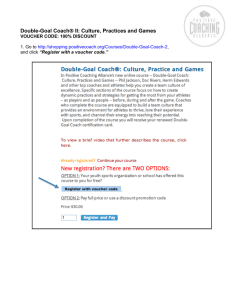

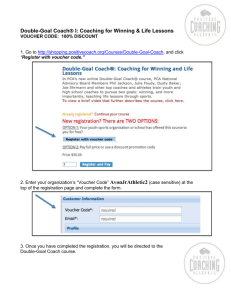

advertisement