Welcome to The Preceptor!

advertisement

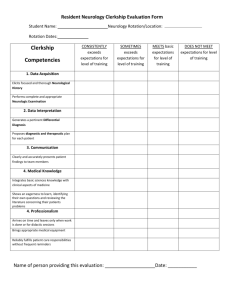

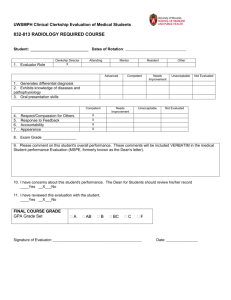

1 Volume 1, Number 1 November 1, 2009 Welcome to The Preceptor! This is LMU‐DCOM’s inaugural issue of what will be a monthly e‐mail faculty development newsletter to aid you as you work with medical students within both an in‐patient and out‐patient setting. We will attempt to cover areas that you feel are needed as you work with the students in your practice. The first few issues will deal with clerkship grading, and then in the months to come we will discuss issues including how to deal with different behavioral issues, dealing with medical legal issues, the teachable moment, etc. Each month we will also have a section titled “Clinical Pearls” – brief descriptions of patient care areas that other physicians have found helpful in their practice. We desire input from you into this area, as well as all areas. If you have found a particular skill or teachable “moment” beneficial, please let us know, and we will add in future issues. Lisa Travis, our medical librarian, will also discuss issues relating to accessing and use of multimedia, on a monthly basis. In the future, with help from our great IT department, we will be adding blogs and chat rooms, allowing you to talk and discuss medical education with your colleagues. Please feel free to contact myself or Lisa Travis at anytime, if you have questions or concerns. This month’s article is primarily taken from a chapter regarding medical education entitled “Evaluation and Grading of Students,” lead authors Louis N. Pangaro, M.D., and William C. McGaghe PhD Enjoy the issue and please feel free to contact me with any questions or concerns. Fraternally, Greg Smith, D.O, FACOFP Produced by Lincoln Memorial University‐DeBusk College of Osteopathic Medicine 6965 Cumberland Gap Parkway | Harrogate, TN 37752 (423) 869‐7200 (phone) | (423) 869‐7078 (fax) 2 Clinical Clerkship Grading The term evaluation frequently has a negative connotation, especially for medical learners engaged in a program of study. Medical students rarely view evaluations as opportunity for improvement even though better performance and public accountability are the principal aims of medical education and the evaluation of its outcomes. Instead, evaluations are seen by learners as hurdles grounded in threat. Evaluations are barriers that channel learner thinking and behavior, frequently motivated by fear or failure, with adverse consequences for those who fall short. Such learner perceptions contrast with faculty intent where evaluation is considered a tool needed to boost student competence and protect the public. Nonetheless, learners perceive the stakes to be high and so it is their anxiety. Evaluation is a process to which most medical learners grudgingly submit. It is rarely a process that they seek and enjoy! Evaluation in medical education has an upside, especially as learners and teachers acknowledge the goal is to produce superb clinicians. When educational evaluation data are seen and used as a tool, not as a weapon, the outlook becomes improvement and mastery rather than enforcement. This outlook also changes the psychological climate toward constructive progress instead of apprehension Purposes of Learner Evaluation There are at least eight purposes for learner evaluation in medical education. Each of these purposes can be addressed in many ways. They are all important, but for different reasons Addressing competence Assessment of medical student competence is a basic responsibility for all programs of clinical education. Such assessments represent accomplishment benchmarks, tangible signs of medical student’s progress along the educational continuum. They depend, of course, on a priori statements of cognitive, procedural, or affective learning goals; high performance standards; and measurements methods that yield reliable data about student achievement. Clerkship directors realize that sound competence assessments provide feedback to students and feedback about educational program effectiveness for faculty and administration. Competence assessment is a cornerstone of quality medical clerkship clinical education. Document learner experience Most clerkship teachers struggle to exercise control over the type or variety of cases seen by medical students in the clinic or hospital. Patients arrive for clinic visits or are admitted to an inpatient service due to concerns about their health, not because the patients want to advance medical education. Individual cases, and the health problems they represent, often present on an uncontrolled, seemingly random basis. Unless patients having different problems are selectively distributed among clinical learners in a controlled way, clinical medicine education can be an uneven experience. Gauge academic progress Similar to competence assessment at important clinical milestones, educational evaluations are also used to gauge and monitor student academic progress more frequently. Medical students are expected to advance through the clinical curriculum on a “critical path” achieving successive program goals both within individual clerkships and across the clerkship year. Wide deviations from that path are a source of concern for clerkship directions. Similar to monitoring 3 infant development using the Denver II development charts, medical student academic progress should be gauged frequently to insure it is within normal means. Predict performance Today’s educational evaluations are often used to forecast performance on future assessments. The success of educational forecasts usually stems from the similarity of the skills begin assessed, congruence of measurement methods, and the time span between the measurements (shorter is better). The conventional wisdom that the “the best way to predict future behavior is to rely on one’s current and past overt behavior” is correct. Rigorous evaluations that produce reliable data give teachers and medical learners a snapshot of each student’s performance status and a window to future student performance. Feedback for improvement A common complaint among medical students is that they rarely receive concrete information about “how they are doing “clinically or educationally. Medical learners are usually eager to discuss their experiences and are anxious to discuss ways in which they boost their fund of knowledge or improve their clinical skill. Performance feedback is a term that is widely used to describe information that gives learners knowledge of the results of their study and clinical work. Given specific feedback about their progress or deficits, medical students can either move to new areas of clinical practice or take steps to improve marginal performance. An educational program needs to have three basic features before useful feedback can be given to learners. First, the program needs to have clear goals that represent a graduated set of milestones for medical students. Second, the program needs to have a means to collect, store, and routinely retrieve data that learners and their teachers can use for educational feedback. Third, the program needs faculty who are willing to take time to candidly review the evaluation data with students, tied to clerkship goals. Effective feedback about educational progress cannot occur unless a plan is in place that identifies goals to be accomplished routinely collects data about student progress and provides frequent opportunities for trainees and faculty to discuss clinical training. Assign grades Clerkships operate inside a clinical department, within an undergraduate medical curriculum, usually wrapped in a university environment. Clerkships are one of many threads in a broad academic fabric. Academic tradition holds that variation in student achievement is acknowledged by the assignment of low and high grades. One of the toughest everyday responsibilities that clerkship directors face is translating data about student performance into medical school grades. This is a medical school and university requirement, a practical reality that comes with the clerkship director’s job, which cannot be avoided. Grades assign value to medical student work. Grades can be given in a normative way (“on the curve”) to compare students against their peers or in ways that compare all students against a fixed achievement standard. The bottom line is that assigning grades to medical students as a sign of their achievement is part of every clerkship director’s job. Fair and impartial grade assignment is a necessary condition of clerkship education. Judge program effectiveness Learner evaluation data including board examination scores, results of OSCEs and SP‐based clinical exams, conative measures, and tests using medical simulations can be employed in a variety of ways to judge the effectiveness of a medical education program. The clerkship works to the degree that medical students meet or exceed a priori expectations about their acquisition of the knowledge, skill, and affective outcomes stated in the program plan. Achievement of clerkship goals is documented by medical student performance data. A clerkship is successful if a high proportion of its medical student’s measure up to expectations based on tough but fair assessments of their learning. 4 Quality Improvement (QI) is another outcome when medical student performance data are used to judge clerkship effectiveness. The clerkship matures and prospers as student performance data accumulate, are studied, and used for program improvement. Medical student performance data not only tell a story about individual learners but also about the quality of clerkships and curricula that shape student learning. Evaluation Goals Medical student’s evaluation has at least five goals to amplify the eight purposes already stated. The five goals are evaluation of: (a) a professional knowledge, (b) technical and procedural skills, (c) professionalism, (d) professional relationships, and (e) physician‐patient relationships. Each evaluation goal is addressed by different measures of medical student achievement. Professional Knowledge Evaluation of professional knowledge has been the mainstay of medical competence evaluation sine the formation of the National Boards. Today, medical knowledge assessment is done via internal (e.g. course, clerkship) and external (NBOME Step 1 and 2) evaluations that rely mainly on multiple choice questions. These evaluations, by intent and format, propel the idea that the acquisition and maintenance of a broad and deep fund of knowledge is essential for medical practice. The primacy of these tests asserts that knowledge acquisition is a basic goal of medical education. Technical and procedural skill Assessment of medical student technical and proficiency has grown in frequency and sophistication over the past decade. Measures are now available that permit objective evaluation of such skills as cardiac auscultation, ACLS maneuvers, and multiple organ system examinations. Most of these measures rely on simulation technology embodied in Standardized Patients or medical simulators. Professionalism Professionalism is expressed in each of a young physician’s character, reliability, honest, ability to keep confidences, and other nonacademic qualities that embody “the good doctor.” Professionalism is more than maturity and less than sainthood: it connotes promises of expertise and duty. In medical circles professionalism is usually conspicuous by its absence and taken for granted when present. Measurement and evaluation of medical professionalism has recently be recognized and expressed as a key outcome of medical education. Teaching and evaluating student professionalism has become one of the highest priorities of medical schools. Teaching is done via customary methods including reading, case discussions, study of professional codes of conduct, and especially by faculty examples in clinical settings. Assessing professionalism is difficult to do with precision. However, such assessments are essential because, “Unprofessional behavior in medical school is associated with subsequent disciplinary action by a state medical board. Professional relationships A fourth evaluation goal is professional relationships. This goal goes beyond integrity to embrace respect for other members of the health care team, administrative staff, and other colleagues. Professional relationships are addressed infrequently in undergraduate medical education while its profile is rising in graduate and continuing education. Recent writings about patient safety teach that clinical patient care is rarely a solitary activity. Instead, nearly all patient care is now delivered by credentials and skills. The emerging educational goal is how to turn a team of experts into an expert team. Professional relationships, individual and team skill acquisition, team member interchangeability, and team cognition are several of the many variables involved in the preparation of expert teams. Another key variable in team effectiveness is dissolution of traditional professionally hierarchies that have existed in clinical medical settings. A 5 growing literature on team training and new professional relationships in medical practice is now beginning to affect medical curricula. Physician‐patient relationships The doctor‐patient relationship has been a hallmark of effective clinical practice from antiquity through Osler and Halsted to the present. Fostering these interpersonal skills and sentiments has been a key feature of medical education and sound clinical practice though sentiments has been a key feature of medical education and sound clinical practice though always threatened by lapses in honesty by either doctor or patient. More recent threats to doctor‐patient relationships include time pressures due to the managed care environment, social class differences, ethnic differences, and many others. Definitions and Important Distinctions in Evaluation Evaluation vs. Grading vs. Assessment Evaluation, rooted in “value” and derived from the Latin valeo (to be strong), indicates a judgment of how well a student strengths correspond with the “values” of the concerned communities, including the department, school, and the profession. Grading implies assignment of a label to the level of the performance achieved, and derives from the Latin word gradus, or step. Grading within a medical school is, effectively, an administrative action classifying the level of performance achieved. While evaluation implies a description in words of how a student is performing, grade implies a concise label that can be expressed with letters, labels, or even numbers (A, B, C, D, etc; Honors, High Pass, Pass, Low Pass, Fail, Incomplete, Withdraw; 96%, 76%...) of the level achieved. Assessment is sometimes used to embrace the entire process of evaluation and grading. It comes from a Latin term meaning to e set a tax). The term assessor would mean someone who “sat at” a judge’s bench). However, it can also be used to refer to the process of measuring something (a radio‐immuno‐“assay”), or of acquiring direct observations about a learner (“sitting next to” the student). The term assessment, then, combines something of the quantitative and qualitative aspects of gathering data for evaluation. While there is some flexibility, perhaps even disagreement, on which terms are used for which part of the process, it can be useful to construct a sequence in which, together, the terms establish a rhythm (assessment‐ evaluation‐grading), and constitutes three phase process that corresponds to the familiar rhythm of clinical medicine that, in turn, reflects the classical sequence of observation‐reflection‐action. Formative vs. Summative Evaluation Formative evaluation is done to “form” or shape the subsequent performance of a learner, specifically by generating and providing feedback. It is done during an experience, and can be done by teachers as frequently as time will allow, but it should also be done formally at specified times, for instance, halfway through an experience. Summative evaluation is done at the end of a unit of time, typically at the end of a clerkship, and “sums” up the student’s performance. Whereas formative evaluation is done primarily for the sake of the student, summative evaluation fulfills our responsibility to society, pronouncing the student ready for the next level of training. Summative evaluation often includes a grade, as well as narrative description of performance and recommendations for improvement. A grade without comment would provide only minimal guidance to a student and would not help the student improve subsequent performance. Therefore, it is recommend that a grade 9label) always be accompanied by an evaluation (descriptive in words). Process vs. Product Measurements; Baseline Measurements This distinction is meant to capture the difference between the curriculum that students experience (process) and their achievements (product outcomes). The concept is often described as the process‐product paradigm. Process measurements could include documentation that students have actually completed clerkship tasks (number of patients seen, number of procedures done), while product measurements include typical, end‐of‐clerkship assessments (NBOME 6 shelf exams). Often, our research tries to document the relationships between what we “do” to students, and how they are changed by the experience. Since research shows that much of what individual students actually achieve depends as much on their personal characteristics as much as on the format curriculum, it is useful to document their “baseline” status, that is what they bring to the clerkship, by having pre‐clerkship measurements such as pre‐clerkship measurements (DCOM will be working to implement a pre‐clinical exam for each core rotation in the coming years) Descriptive vs. Quantitative Methods (“Subjective” and “Objective”) Descriptive methods of evaluation describe a student’s performance using words. Quantitative methods of evaluation describe a student’s performance and yield a numerical score. Most summative grades are a combination of these two methods with some consistency in weighting descriptive methods more than quantitative ones. There is a tendency to refer to quantified examinations as “objective” and narrative evaluations as “subjective.” However, these terms can be misleading. In comparison to descriptive evaluations, a multiple‐choice examination is dispassionate (not caring, for instance, about how confidently a student speaks), has a single “grader: (the scoring device) and its precision and reliability are more easily calculated. However, we should not confuse objectivity with reliability. Even as it relates to test questioning, objectivity (or objectification) does not mean that an assessment (such as a written test) in and of itself has true objectivity. Each step in creating a multiple choice test question, decisions about what to test, and wording of the item, involves judgments that reflect the opinions of the teacher. Unspoken assumptions in the process of converting teachers’ evaluations into grades often lead to students to regard teachers’ evaluations as subjective and arbitrary. Many students protest a lower‐than‐desired grade by arguing that a high score on a multiple test is “objective” (and therefore valid) and that the narrative evaluation describing unprofessional behavior is “subjective” ( and therefore not valid). Yet, descriptive methods can achieve a level of reliability and validity that is sufficient for high stakes decisions. Both assessment methods have a role in determining summative grades and one is not inherently more valuable than the other, so the terms, “subjective” and “objective”‐ which undervalue the former‐should be avoided if possible. Descriptive Evaluation The purpose of descriptive evaluations What is descriptive evaluation? Descriptive evaluation is the term applied to the words instructors use in their assessment of students’ demonstrated competency across the domains of knowledge, skills, and attitudes, and it is usually based on their observations of students over a given period of time. Their words should provide evidence of students’ strengths and weaknesses, give examples of achievements or deficiencies, and serve as the basis for direct, meaningful feedback to the student and for recommending achievement or remediation. Some have described this as “clinical performance appraisal,” which is what is felt that the preceptors of LMU‐DCOM are doing at this present time. Characteristics of descriptive evaluations Unfortunately, descriptive evaluation is often referred to as “subjective” evaluation (as discussed in body of this paper previously). This may have been encouraged by psychometricians and behavioral scientists who have labeled narrative judgments as unreliable and ‘soft,” and have urged faculty to focus on methods that yield “objective” assessments and reflects the bias toward believing that which is expressed in numbers rather than in words. It has been asserted that expert judgment is likely the superior approach to evaluating competence in fields in which science and arts are mixed. It is believed that the use of term “subjective” is detrimental to the evaluation process in that students and faculty often infer that a “subjective” assessment method is inferior to an “objective” method, such as multiple choice examinations. However, “objectivity” does not necessarily result from the strategies of objectification (a set of strategies to reduce measurement error), and the application of these strategies may have undesirable consequences. Descriptive more accurately defines this type of evaluation‐conveying one’s ideas, thoughts, observations, and a synthesized judgment with words. 7 Descriptive evaluation is a component of an overall system of evaluation that also frequently incorporates quantifiable examinations of knowledge and/or skills evaluation. Descriptive evaluation is unique because it involves all aspects of the evaluation system, including evaluators, students, content of evaluation, and learning environment. Additionally, it assesses competencies not easily measured by knowledge in the clinical problem‐solving of direct patient care. Clerkship directors place great emphasis on instructors’ comments in determining grades. Studies of required clerkships in the United States and Canada demonstrated that clinical instructors’ evaluations account for 40‐60% (range 0‐100%) of students’ final clerkship grade. Given the reliance on descriptive evaluations in the grading process, clerkship directors must strive for reliable and valid descriptions. The evaluations should be based on as many direct clinical observations of the students as feasible, describe students’ performance based on uniform criteria established by the clerkship faculty, and cite specific examples of behavior and performance. Evaluators should make specific, behaviorally based comments that cite strengths and weaknesses, thereby providing meaningful feedback to the students. As a result, the evaluations would help clerkship director and faculty teaching in the clerkship discern and tailor interventions for those students who are superior, or marginal, as well as those who are failing. Studies of instructors’ ratings of medical students have shown a remarkable similarity in the elements instructors emphasize. Typically, instructors have emphasized the students’ interpersonal skills in dealing with colleagues and patients, their professional attitudes and behaviors, as well as their ability to apply knowledge and solve clinical problems. However, instructors at various levels of training and experience may place greater emphasis on different factors. Residents are likely to value a student’s procedural skills, work ethic, and motivation to help the team, while attending physicians are likely to place greater value on a student’s knowledge and reasoning skills. The forms you receive from LMU‐DCOM may be most important in the role they play in clearly and concisely communicating goals to teachers. The forms can be one way to communicate expectations for what teachers should assess, and provide guidance and a common language to create a frame of reference form which to evaluate students. Despite some limitations, the forms demonstrate that instructors’ evaluations of students assess the breadth and competency: knowledge and its application, problem‐solving skills, and professional qualities. Many faculty believe that assessing qualities of professionalism may be the most important aspect of evaluating medical students. There may be no better evaluation method to assess professional qualities than faculty and residents who observe performance on a daily basis. In fact, recent studies demonstrate that faculty ratings and comments form the centerpiece of an evaluation process focusing on the professionalism, and those comments made by teachers about students may identify those individuals at risk of future unprofessional conduct. Problems with Descriptive Evaluation Despite the acknowledged importance of descriptive evaluation, there are problems with this type of evaluation. In national surveys, there has been remarkable overlap between the instructors’ and clerkship directors’ perceptions of the most serious problems: inadequate guidelines or lack of information regarding how to handle students with problems; unwillingness to document poor performance; lack of training as evaluators; unclear definition of the role of evaluators; and insufficient definition of the criteria of evaluation. (These areas will be addressed in the next issue of PRECEPT) Instructors’ unwillingness to record negative comments in evaluations does not necessarily mean that instructors are not able or willing to identify “marginal” of failing students. Instructors are often willing to verbally discuss their concerns, but are reluctant to document, on either a rating scale or in written comments these concerns. Reasons for reluctance include fear of legal action, lack of administrative support for unpopular decisions, an unwillingness to be involved in follow through on difficult cases, or “passing the buck” to other evaluators. Also, instructors may feel their role as teacher and mentor may be in conflict with that as an evaluator, or they may have difficulty in delivering “bad” news. A national survey regarding grade inflation showed that 82% of respondents believed that faculty were relctant to give low grades because of students’ expectations of higher grades, fear of legal action, or student “hassle”, belief that students with strong work ethic should not fail, and that assigning higher grades may entice students to their specialty. 8 Of further concern, 43% of the clerkship directors surveyed felt that we are unable to identify incompetent students. These findings are disappointing for several reasons. First, the courts have consistently upheld the judgment of faculty in cases in which students have not met academic or professional standards (will be discussed in a later issue). Second, it would also appear that the “halo effect” (giving higher grades than deserved) continues to strongly influence an instructor’s evaluation, and finally students’ expectations, sense of entitlement, or tenacity in challenging grades appears to have undue influence on instructors. Even if only one instructor states or records a negative comment, it likely has substantial merit. Improving descriptive evaluation How do we improve the evaluation? Many have tried to change multiple forms of the evaluation. Adding items to the evaluation form does not improve reliability. However, adding behaviorally based descriptors in each evaluation category for each level of performance enhances the reliability of instructors’ evaluations, a benefit that can be lost when descriptors are not used. Behavioral descriptors on an evaluation form may contribute to instructors making more detailed written comments. However, trying to improve evaluation by continually refining a form is misplaced effort. Once the fundamentals of the evaluation form are set, one must focus efforts elsewhere. Instructors’ training and sense of ownership of the process are more important than the evaluation form in developing a reliable and valid evaluation system. Including items related to knowledge, skills, and attitudes on a rating scale and asking faculty to assign a number rating does not make evaluation easier or the results more valid. In fact, evaluation form rating scales are less sensitive than instructors’ comments for detecting deficiencies in competency. A study by Battistone et. al demonstrated that using a descriptive vocabulary to assess students crated a more normal distribution and a greater range of ratings than did the use of global numeric method. Evaluation forms with written descriptors of student performance serve two purposes: (a) communicate clerkship and performance goals, and (b) facilitate evaluation Formal Evaluation Sessions LMU‐DCOM students should be evaluated in a formal session after two weeks on a service and then at the end of the service. It is hoped that before each of these sessions takes place, the chief instructor has done a 360 review‐ obtaining information from other physicians, extenders, residents (if applicable) , and nursing staff. With this information, the physician can then give a detailed overview to the student on how they are performing on that service. Studies show that the mid‐point evaluation is extremely beneficial in either encouraging the student, or helping to “right the ship” if there are deficiencies noted by the attending physician. The final session at the end of the rotation allows the attending physician to summarize the rotation and what the student may need to strengthen in future rotations. For our entire DCOM clinical adjunct faculty, please note that there are now three areas of response for you to add any comments, especially using descriptive and behavioral wording that will benefit the student in interviews, as well as during the formation of their Dean’s Letter. (1) One box is for those comments that will be seen by the student. Students often ask the office of clinical medicine if they may see comments on their report, and this is an area where you can add additional remarks for the students. If there has been adequate time spent on review at the mid‐report and final review session with the student, this may not need to be as lengthy, and may not be of major importance, as a month where the student received little feedback. (2) One box for those comments that you want only the chairmen or dean to have access to. Many physician studies show that attending, at time, will be more forthright and open, if they can add comments that, in their belief, would be better discussed with faculty and administration. This box is designed for that purpose. Students will have no access to this information, unless instructed at a later date by the evaluator himself/herself 9 (3) Finally, a box for those comments that will go into the Dean’s Letter. It is imperative that we have a few sentences of the student performance on specific rotations, in that these will be used in for inclusion into the Dean’s Letter, which is essentially a letter of evaluation from the College of Osteopathic Medicine; for use by the student, as they apply for residency positions. The students may have access to this information, only in that they can review the letter in the Dean’s office. They cannot take any part of the Dean’s letter out for their personal use. This box must be filled out before the final evaluation form is submitted to the chair for a grade. Final Comments Please note then when you are grading the student, you are not the individual giving the student their final grade, therefore you are not responsible for the passing or failing of that student. You are grading the student for their performance on that rotation. Your evaluation will then be used by the chair’s and the Clinical Dean’s office to determine the final grade for the student. We at LMU‐DCOM truly appreciate the time and effort you take in training the students as they move onward in their pursuit of becoming a physician Gregory Smith, DO, FACOFP Lincoln Memorial University‐DeBusk College of Osteopathic Medicine 6965 Cumberland Gap Parkway | Harrogate, TN 37752 (423) 869‐7120 (phone) | (423) 869‐7078 (fax) greg.smith@lmunet.edu 10 Lincoln Memorial University-DeBusk College of Osteopathic Medicine (LMU-DCOM) Lon and Elizabeth Parr Reed Medical and Allied Health Library Introduction The Lincoln Memorial University-DeBusk College of Osteopathic Medicine (LMU-DCOM) Lon and Elizabeth Parr Reed Medical and Allied Health Library (Reed Medical and Allied Health Library) provides LMU students, faculty, and staff with timely access to allied health, nursing, and medical literature. Remote access to databases is available to preceptors. Feel free to contact the Medical and Allied Health Librarian at any time for assistance. Full-Text Journal Articles One can click on “Full-Text Journals” on the library homepage and search the full-text journals portal to determine if LMU-DCOM has full-text access to a journal. A video tutorial on how to use this tool is available at http://tiny.cc/u1Yrs. When searching a database, if the article you want is not full-text, it may be available in another database or in the Library’s print collection. Library staff will scan articles from print journals and send them to you at your request. To see if an article is available in full-text from within a database, click on “Find It @ Carnegie-Vincent Library” or “Reed Medical and Allied Health Library.” If the message “Sorry, no holdings were found for this journal” appears, you may request the item via interlibrary loan by clicking on the interlibrary loan link on the same page. To determine if LMU has a particular journal, click on “Full-Text Journals” on the Library Web site and search for the journal. For items not available at LMU, click on the link for “Interlibrary Loan” from the home page and fill out and submit the form. Reference Services The librarian can assist you in: Formulating research strategies Providing direction to finding the most appropriate resources Providing assistance using electronic resources Planning a literature review Assisting in database searching Answering reference questions Searching databases to find citations to books and journal articles Making referrals to associations and agencies as needed Providing complete citations to books and journal articles Developing and managing collections Methods of Contact: Lisa Travis, M.S. – primary liaison for LMU-DCOM Medical and Allied Health Librarian Phone: (423) 869-7132; Fax: (423) 869-7173 lisa.travis@lmunet.edu Literature Search requests: Literature searches may be requested by phone or email. Each request should ideally contain the following information: 1. Name of requestor 2. Requestor’s institutional affiliation 11 3. Requestor’s status (i.e. intern, 1st year resident, 2nd year resident, preceptor) 4. Contact information for requestor, including a follow-up number and email address in case a question or problem arises. Be sure to include the mailing address that information should be sent to. 5. Information requested (be specific, give alternate spelling, names, etc., if applicable) 6. Limiting features such as number of years to be searched, languages, human, age groups, type of article (i.e. review, research, clinical trials, etc.) Electronic Resources Accessing databases through Reed Medical and Allied Health Library You will need a computer with Internet access. You will need your LMU EZ Proxy email account username and password. Go to the medical library’s home page (http://library.lmunet.edu/medlib) Choose the database you wish to search under the heading for “Quick Links” or, for a full listing of databases, click on “Databases,” and then choose “DCOM” or another subject area. Choose the type of database you wish to search and then choose the database you wish to search. American Botanical Council Includes informative articles, reviews, monographs, a magazine, and a newsletter on herbs. Annual Reviews Annual Reviews provides researchers, professors, and scientific professionals with a definitive academic resource in 37 scientific disciplines. Annual Reviews saves researchers time by synthesizing the vast amount of primary research literature and identifying the principal contributions in your field. Bates’ Visual Guide to Physical Examination, 4th edition, 2005 Includes physical examination videos of systems, body regions, and patients by age. Bookshelf This is a growing collection of searchable electronic books on a variety of medical topics. CINAHL (Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature) with Full Text Indexes over 2,950 biomedical, healthcare, nursing, and allied health journals back to 1981; provides full-text access to nearly 600 journals. CLIPP (Computer-assisted Learning in Pediatrics Program) Includes 31 interactive virtual patient cases for third-year medical students to use during their pediatric clerkship. The cases are designed to cover all of the core content of the curriculum of the Council on Medical Student Education in Pediatrics (COMSEP). The Cochrane Library Includes Cochrane systematic reviews, other systematic review abstracts, technology assessments, economic evaluations, and individual clinical trials. Early American Manual Therapy This collection of freely-available materials includes numerous electronic books from the late 1800s and early 1900s related to osteopathy. eMedicine One must register and create your own login for this resource. Includes 6,500 articles written by 10,000 physician contributors in numerous specialties. 12 Epocrates Online One must register and create your own login for this resource. Includes information on diseases, drugs, and drug interactions. Also includes a pill identifier and helpful tables. FreeBooks4Doctors! Includes 365 books that are freely available online. Users may search by keyword, specialty, and title. Full-text journals This service is available through Serials Solutions E-Journal Portal and allows users to determine if LMU has full-text access to a particular journal as well as see lists of full-text journals in different subject areas. Health and Wellness Resource Center This database is a user-friendly place for consumers to start researching health topics. It provides full-text access to health related magazines, journals, pamphlets, newspapers, encyclopedias, videos, and even Web sites. Health Reference Center – Academic This database provides full-text access to respected nursing, allied health, and medical journals; it also includes consumer health magazines, newsletters, pamphlets, newspaper articles, topical overviews, and reference books. Many images are also included. Health Source: Consumer Edition Health Source: Consumer Edition offers full-text access to nearly 80 consumer health periodicals. Also contains more than 5,100 Clinical Reference Systems reports (in English and Spanish); Lexi-PAL Drug Guide, which covers 1,300 generic drug patient education sheets with more than 4,700 brand names; and Merriam-Webster's Medical Desk Dictionary. Health Source: Nursing/Academic Edition The Nursing/Academic edition of Health Source provides full-text access to 539 periodicals, 437 of which are peerreviewed. It also features citations and abstracts 833 periodicals, 719 of which are peer-reviewed. HIT: Health Information Tennessee This is the gateway for demographics, statistics, and information on health care in Tennessee. Lexi-Comp ONLINE Lexi-Comp ONLINE includes non-biased information on drugs and natural products as well as medical calculations, a drug ID component, an interactions component, I.V. compatibility information, FDA special alerts, updates on medical safety issues, and more. MEDLINE Includes 19 million citations dating back to 1948, including limited-full text articles. This version of MEDLINE is only accessible while one is affiliated with LMU; therefore, unless a user is familiar with the FirstSearch interface, librarians recommend that one use PubMed, the freely-available version of MEDLINE that can be used by anyone anywhere. Micromedex Micromedex is a comprehensive medical reference on drugs, diseases, acute care, toxicology, alternative medicine, and patient education and care. Disclaimer: According to license restrictions, this resource can only be used for educational and training purposes by Lincoln Memorial University students and faculty in the health sciences and is not to be used for any clinical care, emergency, or commercial purpose. Users are not to access this resource from a clinical setting. 13 MSU Osteopathy Digital Collection These freely-available collection of electronic materials includes early osteopathy textbooks, collections of articles, and an autobiography of Andrew Taylor Still. NetLibrary LMU’s collection of digital books on a wide range of subject areas includes over 1,700 books with “health” or medicine” as subject headings. OSTMED.DR This digital library of full-text osteopathic literature includes over 40,000 items and builds on OSTMED, which was a collection of bibliographic index of osteopathic literature. Piper Online Catalog The online library catalog allows users to search LMU’s holdings of print and electronic books as well as audiovisual materials. Primal Anatomy (Anatomy.tv) Includes interactive modules with text for the head and neck, axilla, spine, thorax & abdomen, knee, hip, hand, pelvis & perineum, and foot. Also includes a study guide and test bank. Also includes essential regional anatomy, acupuncture anatomy, and pilates anatomy. Also includes surgery videos and animations for the axilla, knee, knee arthroplasty, hip arthroplasty, and podiatric medicine. Procedures Consult This subscription provides access to 42 internal medicine procedures with videos and tests. Users can choose to view a quick review or full details for each procedure. Procedures include defibrillation, general splinting techniques, local anesthesia, lumbar puncture, and nasogastric intubation. Program Resources The Reed Medical and Allied Health Library provides links to freely-available, interactive Web sites of use in osteopathic medicine. Program Resources include Web sites with games, animations, videos and tutorials for anatomy, ecgs, diagnosis, physical assessment, and other subjects. To view the Program Resources, click on “Osteopathic Medicine” under the heading for Program Resources on the Reed Medical and Allied Health Library home page at http://library.lmunet.edu/medlib. ProQuest Health & Medical Complete Provides coverage from leading health journals and essential medical journals in key medical specialties. Indexes over 1,530 publications and provides the full-text for over 1,270 publications. PsycINFO This database contains more than 2.6 million citations and summaries of journal articles, book chapters, books, dissertations and technical reports in psychology and related disciplines. Some of the journal articles are offered in full text. Ninety-eight percent of the covered material is peer-reviewed, and content dates back to the early 1800s. PubMed PubMed is a service of the U.S. National Library of Medicine that includes over 19 million citations from MEDLINE and other life science journals for biomedical articles in the fields of medicine, nursing, dentistry, veterinary medicine, health care systems, and preclinical sciences back to 1948. It also includes links to the molecular biology databases maintained by the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). 14 ScienceDirect Health & Life Sciences College Edition This database includes over 900 full-text journals within the health and life sciences. Coverage is from 1995 to the present. STAT!Ref Medical Provides access to 34 electronic medical books, including textbooks for LMU-DCOM. Includes Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine, several Lange books, ACP Medicine, and Review of Medical Physiology by Ganong. Includes three resources that contain detailed drug information and one resource that covers natural products. Also includes Stedman’s Medical Dictionary. STAT!Ref Nursing Provides access to 14 electronic books, two of which are useful to LMU-DCOM: Guide to Culturally Competent Health Care (2005) and Laboratory Tests and Diagnostic Procedures with Nursing Diagnoses (2008). Thieme ElectronicBook Library Includes 39 electronic books. Subjects include anatomy, radiology, biochemistry, microbiology, genetics, and neurology. UpToDate This is an evidence-based resource with over 80,000 pages of original, peer-reviewed text to allow practitioners to keep current with new clinical developments, be more confident in diagnosis and treatment decisions, and answer clinical questions more efficiently. It offers comprehensive information in the specialties of adult primary care, allergy and immunology, cardiology, critical care, emergency medicine, endocrinology, family medicine, gastroenterology, gynecology, hematology, hepatology, infectious diseases, nephrology and hypertension, obstetrics, oncology, pediatrics, pulmonology, rheumatology, surgery, and women’s health. WISE-MD (Web Initiative for Surgical Education) Includes 10 interactive modules for third-year medical students to use during their surgery clerkship. More modules are planned. Current modules cover abdominal aortic aneurysms, adrenal adenoma, anorectal disease, appendicitis, carotid stenosis, cholecystitis, colon cancer, hernia, skin cancer, and trauma resuscitation. WISE-MD was jointly developed by the Department of Surgery and the Division of Educational Informatics at NYU in furtherance of this mission with the support of the American College of Surgeons (ACS) and the Association for Surgical Education (ASE). In addition to these databases, the library also has other databases, particularly multidisciplinary ones like Academic Search Premier, that include books and journals that are useful to medical faculty, staff, residents, interns, and students. Interlibrary Loans At your request, the Library will borrow books and materials from other libraries and ship them to you. Use the “Interlibrary Loan” link on the Library’s Web site to request an interlibrary loan or, from within a database, request the loan upon determining that LMU does not have the item after clicking on “Find It @ Carnegie-Vincent Library” or “Reed Medical and Allied Health Library.” You should return borrowed materials to the Carnegie-Vincent Library on or before the due date indicated on the lending slip. You are responsible for the costs of return shipping. LoanSome Doc LoansomeDoc enables PubMed users to order documents. It is available to users in the U.S. and internationally. LoansomeDoc makes ordering articles easier. Users simply conduct a literature search in PubMed and select the article(s) they wish to order by clicking on the box(es) to the left of the citation(s) and then begin the ordering process by choosing “Send To” and then “Collections.” A requestor then enters his/her LoansomeDoc user ID and password; if the requestor does not have a LoansomeDoc user ID and password, he or she may freely register and set up a login with LoansomeDoc. 15 See http://library.lmunet.edu/medlib/loansome-doc for how to register to use LoansomeDoc with the Reed Medical and Allied Health Library. Once the request is processed and completed, the journal articles will be sent to the Reed Medical and Allied Health Library and then forwarded to the requestor. Circulation Services The Reed Medical and Allied Health Library Circulation Services is located near the entrance to the Carnegie-Vincent Library within the Harold M. Finley Learning Resources Center. Circulation Services staff provides: Circulation of books owned by the Reed Medical and Allied Health Library and the Carnegie-Vincent Library Renewals of circulating materials Holds Overdue notices Fines & fees for overdue and/or lost library materials Method of Contact: Phone: 423-869-7079 Fax: 423-869-6426 Email: library@lmunet.edu Normal Hours of Operation: Monday – Thursday 8:00 a.m. – 11:00 p.m. Friday 8:00 a.m. – 4:30 p.m. Saturday 10:00 a.m. – 5:00 p.m. Sunday 2:00 p.m. – 11:00 p.m. Borrowing Books from the Reed Medical and Allied Health Library and the Carnegie-Vincent Library Books and other circulating items in the Reed Medical and Health Library collections may be checked out and mailed to requestor. Length of borrowing period will depend on the item type, i.e. book, video, etc. Renewals Renewals may be requested for circulating library materials that are not overdue and have no holds placed. The borrower may request a renewal via phone, fax, or email. Holds If a requested book is already in circulation, a hold may be placed on that item. When a hold is triggered (i.e. the item is returned), the requestor will be notified of the item’s availability. If the requestor is not in the Harrogate area, the item will be mailed to the requestor. Return postage is the borrower’s responsibility. Fines/Fees The fine for overdue materials is $.15 per item per day. Fees for a lost item: Replacement cost, plus accrued overdue fines, plus $20.00 processing fee (per item). All fines & fees must be satisfied prior to completion of the A-OPTIC program. Lisa Travis, M.S. Medical and Allied Health Librarian Phone: (423) 869-7132 Fax: (423) 869-7173 lisa.travis@lmunet.edu