PHYSICIAN Teaching The

advertisement

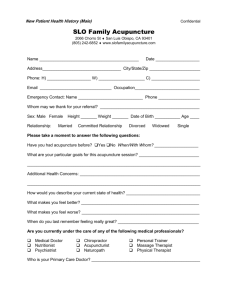

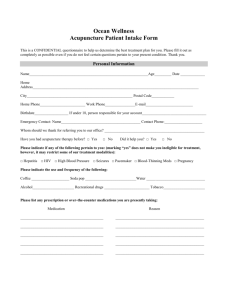

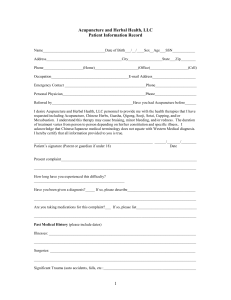

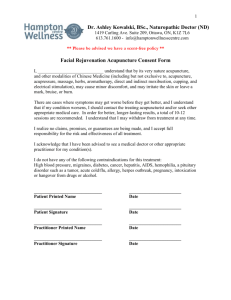

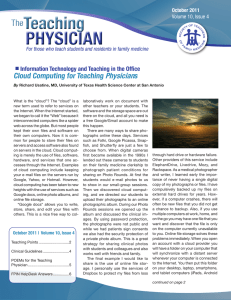

Teaching PHYSICIAN The April 2012 Volume 11, Issue 2 For those who teach students and residents in family medicine n Clinical Guidelines That Can Improve Your Care Acute Rhinosinusitis in Adults, University of Michigan Guidelines for Clinical Care By Diana L. Heiman, MD, Quillen College of Medicine, ETSU I figured that I’d have the column get “blown away” for the final installation. Rhinosinusitis doesn’t seem to be as common a presenting complaint as in the past. I’m not sure why, but maybe it’s been related to a decrease in antibiotic prescriptions over the years from me. Maybe patients think they will get antibiotics more easily from the emergency department or an urgent care center. Regardless, the University of Michigan has updated their 2007 guideline on the diagnosis and treatment of rhinosinusitis. Acute rhinosinusitis is defined as inflammation of the paranasal sinuses and the nasal cavity lasting no longer than 4 weeks. It includes viral and bacterial etiologies, but bacterial infection follows the common cold in only five in 1,000 patients. Diagnostic predictors of bacterial rhinosinusitis are listed in Table 1. Treatment of viral rhinosinusitis is supportive, but if bacterial infection is likely, antibiotic treatment can be considered. The guideline points out April 2012 | Volume 11, Issue 2 Teaching Points..............................2 FPIN HelpDesk Answers................4 POEMs...........................................5 that antibiotics have not been shown to decrease complications or the risk of progression to chronic rhinosinusitis. Side effects, development of antibiotic resistance, and allergic reactions to the antibiotics should be considered along with the severity of symptoms and likelihood of bacterial infection before prescribing the antibiotics. Antibiotic therapy increases symptom resolution at 2 weeks only by 15%, from 70% without antibiotics to 85% with antibiotics. Recommended first-line antibiotic therapy is amoxicillin and trimethoprim/ sulfamethoxazole for 10–14 days. If the patient is allergic to both first-line antibiotics, doxycycline also for 10–14 days or azithromycin 500 mg daily for 3 days are then recommended. (Cefuroxime, clarithromycin, cefprozil, cefinidir, and levofloxacin may also be considered if allergies exist but in general are much more expensive alternatives.) For incomplete resolution of symptoms, lengthening the course of therapy to 3 weeks should be done. If the patient still fails treatment, secondline antibiotics should be considered. These include high-dose amoxicillin, amoxicillin-clavulanic acid, levofloxacin, or moxifloxacin. Recommending the use of ancillary agents for symptom control is a part of therapy. Therapies with good evidence for symptom control are oral and topical decongestants, topical ipratropium, and high-dose nasal steroids. No Table 1 Predictors of Acute Bacterial Rhinosinusitis • Maxillary toothache • Poor response to decongestants • Patient report of colored nasal discharge • Visualization of purulent secretions on exam • Symptoms beyond 10 days significant benefit has been seen from the use of nasal saline, standard dose guaifenesin, steam, or antihistamines (unless allergic rhinitis is an underlying condition). See the guideline for specific doses.1 As far as imaging, it is not recommended in acute cases. Computed tomography (CT) is the recommended imaging modality but is only recommended if symptoms last more than 3 weeks or if the patient has more than 3 recurrences in a year. The scan should be performed when the patient is symptomatic to confirm the diagnosis and determine if referral to otolaryngology is warranted. Reference 1. University of Michigan Health System. Acute rhinosinusitis in adults. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Health System, August 9, 2011. Caryl Heaton, DO, UMDNJ-New Jersey Medical School, Editor Diana Heiman, MD, Quillen College of Medicine, ETSU, Coeditor Teaching PHYSICIAN Teaching PHYSICIAN The n Teaching The Goodbye to the Teaching Physician Newsletter Points—A 2-minute Mini-lecture Use of Proton Pump Inhibitors By Lori Dickerson, PharmD, Trident/MUSC Family Medicine Residency Program Editor’s note: The process of the 2-minute mini-lecture is to get a commitment, probe for supporting evidence, reinforce what was right, correct any mistakes, and teach general rules. Lori Dickerson, PharmD, at the Trident/ MUSC Family Medicine Residency Program in North Charleston, SC, authored this scenario. In this scenario, Dr Dickerson (Dr D) works with a first-year resident (R1) in considering when to prescribe proton pump inhibitors. R1: Dr Dickerson, which is the best acid blocker? Across the street, they tell me it’s Nexium. Dr D: There is some evidence behind that choice. But, what are you treating? R1: The patient has GERD. Dr D: What makes you call it that? R1: She gets a burning pain in her epigastrium with bloating and some nausea. Are you questioning the diagnosis? It’s not an ulcer—she had an upper endoscopy that was negative for ulcer. Dr D: OK, so no ulcer. But did they describe esophagitis? [They look at the endoscopy report.] Dr D: Normal esophagus, stomach, and duodenum. It’s not irritable bowel syndrome—do you know why? R1: There’s no constipation or diarrhea. Dr D: Right. And, also, the pain is not relieved by a bowel movement. So what diagnosis are we left with? It’s not an ulcer, esophagitis, or irritable bowel? 2 April 2012 | Volume 11, Issue 2 R1: Non-ulcer dyspepsia. Right. You already gave me an article on this issue.1 So I was right, even if I said GERD, and it’s dyspepsia. What about Nexium for treatment? Dr D: When that article came out in 2004, it was based on the latest information. But there was just a study that said there is no clear benefit from a proton pump inhibitor.2 R1: So I will add the diagnosis of nonulcer dyspepsia to my differential diagnosis of upper abdominal symptoms. And I shouldn’t reach for a proton pump inhibitor so automatically in the future. There are other options listed in that article. But what is the downside to prescribing a proton pump inhibitor? Everybody writes for them. Dr D: Funny you should say that. Let’s go to drugs.com and look at the 200 most widely prescribed medications in 2010. There’s Nexium at the top.3 So that’s a lot of money spent. And, if it’s not helpful, then that’s money wasted. What about other reasons not to prescribe a proton pump inhibitor? R1: There was an article about how blocking the stomach acid seems to contribute to getting hospital acquired pneumonia.4 It also affects other medications. And… Dr D: Right, other things, too, like low magnesium, fractures, risk of C. difficile. Dr D: Right. That’s the indication with the most evidence supporting its use. But not for all patients admitted to the hospital. Over half of all patients admitted to the hospital receive acid suppressive medications during hospitalization, and about half of those hospitalized patients are receiving the acid blocker as a new medication. Most of the time, the patient does not even need the medication in the hospital. But—worse then that—about half of the patients who get a new prescription for an acid blocker during the hospital stay actually continue the medication at discharge. So we tend to start this medication during hospital stays—for no good reason in the majority of cases. R1: OK. Forget proton pump inhibitors. Let’s talk about a safer topic—what about aspirin for primary prevention? [smiles] References 1. Dickerson LM, King DE. Evaluation and management of nonulcer dyspepsia. Am Fam Physician 2004;70:107-14. 2. Wong WM, Wong BCY, Hung WK, et al. Double blind, randomized, placebo controlled study of four weeks of lansoprazole for the treatment of functional dyspepsia in Chinese patients. Gut 2002;51:502-6. 3. www.drugs.com/top200.html. Pharmaceutical sales: 2010. Accessed March 24, 2012. 4. Herzig SJ, Howell MD, Ngo LH, Marcantonio ER. Acid-suppressive medication use and the risk for hospital-acquired pneumonia. JAMA 2009;301(20):2120-8. Alec Chessman, MD, Medical University of South Carolina, Editor This is the last issue of the Teaching Physician. Taking its place is TeachingPhysician.org, a comprehensive web-based resource that connects medical schools and residency programs to community preceptors. It delivers videos, tips, answers to frequently asked questions, and links to in-depth information on precepting topics such as: • Preparing a practice team for a student or resident • Integrating a student into office routines • Setting expectations • Teaching strategies • Giving feedback • Evaluating learners • Billing issues Ask your institution about receiving this resource. www.teachingphysician.org R E G I S T E R B Y M A R C H 1 9 T H & S AV E $ 7 5 ! STFM 45th Annual Spring Conference April 25-29, 2012 Sheraton Seattle Hotel Seattle, Washington The Teaching Physician is published by the Society of Teachers of Family Medicine, 11400 Tomahawk Creek Parkway, Suite 540, Leawood, KS 66211 800-274-7928, ext. 5420 Fax: 913-906-6096 tnolte@stfm.org STFM Web site: www.stfm.org Managing Publisher: Traci S. Nolte, tnolte@stfm.org Editorial Assistant: Jan Cartwright, fmjournal@stfm.org Subscriptions Coordinator: Jason Pratt, jpratt@stfm.org Editors Clinical Guidelines That Can Improve Your Care Caryl Heaton, DO, editor heaton@umdnj.edu Diana Heiman, MD, coeditor heiman@etsu.edu Family Physicians Inquiries Network (FPIN) HelpDesk Jon Neher, MD, editor ebpeditor@fpin.org Information Technology and Teaching in the Office Richard Usatine, MD, editor usatine@uthscsa.edu Thomas Agresta, MD, coeditor Agresta@nso1.uchc.edu POEMs for the Teaching Family Physician Mark Ebell, MD, MS, editor ebell@msu.edu Teaching Points—A 2-minute Minilecture Alec Chessman, MD, editor chessmaw@musc.edu R1: But we need to use it for patients admitted to the Intensive Care Unit, right? Don't miss the nation’s most energized networking forum for family medicine educators. April 2012 | Volume 11, Issue 2 3 Teaching PHYSICIAN Teaching PHYSICIAN The The From the “Evidence-Based Practice” HelpDesk Answers Published by Family Physicians Inquiries Network (FPIN) n Is Acupuncture Safe and Effective for Smoking Cessation? By Luis Otero, MD, David Grant FMR, Travis AFB, CA Evidence-based Answer Although acupuncture appears to be safe (SOR: B, based on surveys of adverse reactions), there is currently no consistent evidence showing that acupuncture is an effective intervention for smoking cessation. (SOR: B, based on a meta-analysis of low-quality RCTs.) In 2011, the Cochrane collaboration published a review of the existing literature examining acupuncture’s effect on smoking quit rates.1 Results of 18 comparisons of acupuncture with sham acupuncture in the short term (up to 6 weeks after quit date) with 1,385 patients in the treatment arm and 1,143 in the control arm found a risk ratio of 1.18 (95% CI, 1.04–1.33) favoring acupuncture. Of note, the strong effect of a single trial was the major contributor to this positive result. In the long-term (6–12 months after quit date) analysis of six studies with 881 patients in the treatment arm and 781 patients in the control arm, acupuncture did not alter quit rates (RR=1.03; 95% CI, 0.82–1.35). When a waiting list or no intervention was 4 April 2012 | Volume 11, Issue 2 used as a control in three studies (197 intervention patients and 196 control patients), the pooled results also showed no significant effect (RR=1.79; 95% CI, 0.98–3.28). Furthermore, in comparison with nicotine replacement therapy (496 patients), acupuncture (418 patients) was found to be less effective in both the short term (RR=0.76; 95% CI, 0.59–0.98) and the long term (RR=0.64; 95% CI, 0.42–0.98).1 The Cochrane review noted significant heterogeneity and risk of bias in several of the published trials. A further limitation was the combination of disparate forms of acupuncture with different treatment periodicity into a group effect. Safety outcomes were not addressed.1 An investigation of physician acupuncturists in Germany examined the question of safety.2 In the study, 9,249 practitioners reported on 97,733 patients over a 10-month period. Serious adverse events reported as likely or certainly attributable to acupuncture were reported to be rare and included two pneumothoraces and one vasovagal hypotensive episode. A prospective survey of acupuncturists performed in the United Kingdom also looked at the question of safety.3 A total of 547 practitioners reported on 34,407 treatments over a 4-week period. No serious adverse events (defined as events requiring hospital admission, leading to permanent disability, or resulting in death) were reported. Mild transient reactions, such as bruising or pain, were associated with 15% of treatments. Minor adverse events were found in 43 instances (0.1%), the most common being severe nausea, fainting, and dizziness. Acknowledgments: The opinions and assertions contained herein are the private views of the authors and are not to be construed as official or as reflecting the views of the Medical Department of the US Army or the US Army Service at large. References 1. White AR, et al. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011;(1):CD000009. [LOE 2a] 2. Melchart D, et al. Arch Intern Med 2004; 164(1):104–105. [LOE 2b] 3. MacPherson H, et al. BMJ 2001;323(7311):486487. [LOE 2b] SOR—strength of recommendation LOE—level of evidence Jon O. Neher, MD, University of Washington, Editor HelpDesk Answers are provided by Evidence-based Practice, a monthly publication of the Family Practice Inquiries Network (www.fpin.org). n POEMs for the Teaching Physician Prostate Cancer Screening: No Mortality Benefit After 13 Years of Follow-up Clinical Question: Does screening of asymptomatic men for prostate cancer improve mortality? Study Design: Randomized controlled trial (single-blinded) Funding: Government Setting: Population-based Synopsis: We have previously reported on the first report from the PLCO study (http://www.essentialevidenceplus. com/content/poem/110501) in which men between the ages of 55 years and 74 years at 10 centers were randomized to receive prostate cancer screening (annual PSA for 6 years plus digital rectal examination for 4 years) or no scheduled screening. The current study reports additional follow-up (up to 13 years). The authors report having 92% follow-up at 10 years after study enrollment but at the time of this publication, only 57% of the participants had 13 years of follow-up. The cumulative incidence rate of prostate cancer was 108 and 97 per 10,000 person-years in the screened and control groups, respectively. We would need to screen approximately 885 men annually to detect one additional prostate cancer. However, the cumulative mortality rates were virtually identical (3.7 and 3.4 per 10,000 person-years, respectively). Certainly, the 10-year data appear to be similar to the 13-year data. The authors found no difference in mortality whether men were screened before entering the trial or by age or comorbidity. It appears that there is no overall mortality benefit to screening asymptomatic men for prostate cancer. Bottom Line: After more than a de- cade of follow-up from the Prostate, Lung, Colorectal, and Ovarian Cancer study (PLCO), there appears to be no mor tality benefit to screening asymptomatic men for prostate cancer. (LOE = 1b) Source article: Andriole GL, Crawford ED, Grubb RL 3rd, et al, for the PLCO Project Team. Prostate cancer screening in the randomized prostate, lung, colorectal, and ovarian cancer screening trial: mortality results after 13 years of followup. J Natl Cancer Inst 2012;104(2):125-32. Those Unnecessary “Little” Tests Add Up: $5 Billion/Year in the US Clinical Question: What is the financial impact of the typical practices of little benefit used in primary care? Study Design: Descriptive Funding: Self-funded or unfunded Setting: Population based Synopsis: A previous project conducted in three primary care specialties identified the “top 5” activities in each specialty that were thought to be common in practice but of little benefit to patients (Arch Intern Med 2011;171(15):138590). In this report, the authors used data from two US surveys of practice— the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey and the National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey—to estimate the frequency of these activities. They calculated the proportion of times each of the top five activities was performed as reported by these surveys and used this percentage to determine the additional costs to the health care system. The costs lined up as follows (in millions of US dollars for 1 year): General medical examination tests or procedures Routine complete blood count in adults (56% of visits): $32.7 Basic metabolic panel in adults (16%): $10.1 Annual electrocardiography (19%): $16.6 Urinalysis (18%): $3.4 Antibiotics for viral pharyngitis (41%): $116.3 Cough medicines for children (12%) : 10.3 Brand name statins(atorvastatin or rosuvastatin) instead of generic statins (34.6%): $5817 ($5.8 billion) Papanicolaou tests for patients younger than 21 years (2.9%): $47.7 DEXA scans for women younger than 64 years (1.4%): $527.4 Bottom Line: The routine “little” practices used in primary care add up when multiplied across the US health care system. Removing typical but not useful screening tests and procedures from health maintenance examinations and avoiding treating viral pharyngitis with antibiotics and high cholesterol levels with more expensive alternatives could put more than $5 billion back into the health care system. The list of not useful habits, their frequency of use in the United States, and their total costs can be found in the synopsis. (LOE =5) Source article: Kale MS, Bishop TF, Federman AD, Keyhani S. “Top 5” lists top $5 billion. Arch Intern Med 2011;171(20):1856-8. LOE—level of evidence. This is on a scale of 1a (best) to 5 (worst). 1b for an article about treatmen is a well-designed randomized controlled trial with a narrow confidence interval. Mark Ebell, MD, MS, Michigan State University, Editor POEMS are provided by InfoPOEMs Inc (www.infopoems.com) Copyright 2012 April 2012 | Volume 11, Issue 2 5