4 E C :

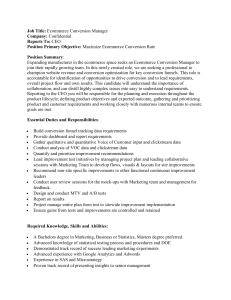

advertisement