The WTO/World Bank Conference on Developing Countries' in a Millennium Round

advertisement

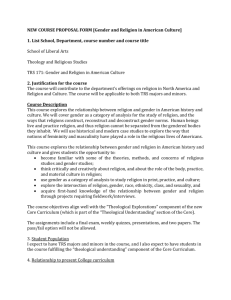

The WTO/World Bank Conference on Developing Countries' in a Millennium Round WTO Secretariat, Centre William Rappard, Geneva, 20-21 September 1999 Trade Facilitation: Technical Regulations and Customs Procedures Patrick A. Messerlin Institut d’Etudes Politiques Jamel Zarrouk Arab Monetary Fund 13 September 1999 Trade Facilitation: Technical Regulations and Customs Procedures Patrick A. Messerlin and Jamel Zarrouk Trade facilitation, especially issues related to customs procedures and technical regulations and standards (TRS) have become an increasing source of concern for the international business community and source of conflict in the WTO. Industrial countries perceive that customs procedures in developing countries and emerging markets have not evolved enough to adjust to the rapidly growing volume of trade of the last decade. Their complaints are echoed by service providers, such as express mail courriers which depend heavily on customs procedures for providing certain features of their services (the guaranteed time of delivering a mail or a parcel) and which manipulate a substantial proportion of all customs entries (more than 30 percent in their largest markets). In response, developing countries have increasingly raised concerns about the imposition of ever expanding technical regulations and standards (hereafter TRS) by industrial countries.1/ Developing countries argue that TRS are beyond their technical competence or not taking into account special development needs and technological problems [UNCTAD, 1999]. Conversely, complaints are also expressed by developing countries about the “spaghetti bowl” of rules of origin included in the customs procedures of the industrial countries (in particular, those which are hubs of regional agreements), while industrial countries complain about the adoption by some developing countries of technical regulations that have no scientific basis and appear to be used to substitute for quantitative restrictions and similar instruments. These developments suggest that it makes sense to examine customs regulations and TRS together, under the general headline of trade facilitation. Both components of the trade facilitation agenda give rise to the same challenge: how to minimize the unnecessary burden for trading partners of the national application of national regulations, which reflect each WTO Member’s right to regulate its own economy as it wishes. One reason these complaints have become noisier is that many tariffs and “standard” non-tariff barriers such as quantitative restrictions or voluntary export restrictions have been reduced or eliminated. But other factors can explain the fact that trade facilitation is rising on the agenda of trade negotiations as well. First, the growth of intra-firm trade (where the same firm is at both ends of the trade flows concerned) makes large firms less willing to accept external constraints on their cost-minimized internal production process. Second, small and medium enterprises (either SMEs in large industrial countries, or large firms in smaller developing economies) are playing an increasing role in world trade: customs procedures and /Standards are, by nature, voluntary: they consist in “a document, established by consensus and approved by a recognized body, that provides, for common and repeated use, rules, guidelines or characteristics for activities or their results, aimed at the achievement of the optimum degree of order in a given context” [ISO Guide, 1991]. 1 1 TRS are for them new problems -- in sharp contrast with large firms having an experience in these issues, and/or a better grip on them -- fueling the feeling of unfair competition. Third, differing customs regimes and requirements, and duplicate standards applied to the same international transaction may be best explained by regulatory regimes that range from a strong tradition of centralized (often public) action to an almost complete lack of action by central authorities. Last but not least, TRS are closely related to two issues of increasing importance in the world trade system: health and environment. This importance is being greatly magnified by small and well-organized interest groups/NGOs which have strong views on what are the “best” TRS, are able to convey their messages quickly and across frontiers through Internet connections, and are skilled in getting attention in the media. What can then be done during the coming decade in the TF field? In order to answer this question, the paper is organized as follows. Section 1 tries to provide a sense of the exact importance of the TF topics by asking two questions: (i) to which extent developing and emerging countries are more, or less, concerned by TF problems than industrial countries through their trade flows with industrial countries; and (ii) how frequent and important have been TF issues in WTO dispute settlement cases? Section 2 looks at the possibility for unilateral, regional and multilateral actions for addressing the issues raised by the design of TRS, and what they imply for WTO rules. Section 3 does the same for issues that arise in the design of customs procedures. Section 4 discusses mechanisms for the enforcement of TRS and customs-related regulations. Throughout, we use the EC experience in managing these two TF issues as a guideline for assessing what could be done at the multilateral level. Section 5 concludes. Two general lessons emerge from the paper. First, a top-down approach aiming at eliminating TRS-related trade conflicts by adopting similar TRS among trading partners (through harmonization or mutual recognition) is likely to be unproductive for the WTO, and to be a source of distortions when followed by regional groups of countries. By contrast, public initiatives at the level of enforcement -- following a bottom-up approach -- seem to offer much better perspectives if TF activities are increasingly conceived as services, and as such, subject to domestic regulatory reforms and liberalization. Second, private initiatives can be very useful at both levels (design and enforcement) because they can be much more flexible and more responsive to consumers’ demand than public actions, and because the risks of private collusive behavior (which would lead to trade distortions) could be managed by competition authorities (to the extent that they are independent from governments’ and medias’ pressures). 1. The Extent of TRS and Customs Requirements TRS are introduced for a wide range of reasons (including for giving the impression of public action). They can be applicable to products, production or producers (licensing requirements for service suppliers), and to consumption (bans of certain products for certain use, see below the beef hormone case). The scope and type of product and process-specific 2 regulation will reflect a society’s attitudes toward the level of acceptable risks, its knowledge and ability to manage risk, and its environmental factors (endowments). As is well known, the result of differences between countries in any of these determinants is often that domestic markets are sheltered from foreign competition. The last fifty years have witnessed a considerable increase of TRS in almost all the countries. In fact, the main force behind EC efforts for creating European TRS during the 1970s has been the boom of new TRS adopted by Member states (in 1992, EC Member states were enforcing more than 80,000 norms, compared to less than 2,000 European norms [WTO TPR, 1993, p.111]). Since then, EC TRS represent the largest body of EC law: in less than 25 years, 503 Directives (laws in EC parlance) on TRS have been adopted -- more than a third of all the 1381 Directives adopted by the EC since 1958 and included in the 1997 acquis communautaire [Annual Report to the Parliament on Community Law, 1998]. The two next largest packages of Directives are agriculture and environment, respectively 383 and 144 Directives -- a substantial proportion of them including TRS-related regulations. To a lesser extent, the same observation could be done for customs procedures for a wide variety of reasons: for instance, from the need to create new tariff codes for products subject to antidumping duties to always longer and more detailed rules of origin. This general evolution in most of the WTO Members has led to a multiplication of duplicative requirements at the borders -- from testing and certification to the origin of the imported products -- which have rapidly become more important as a barrier to international trade.2 It has been estimated that over 60 percent of U.S. exports are subject to mandatory health, safety, and related TRS. For exports to the EC, government-issued certificates were required for 45 percent of these goods, whereas private, third party certification was accepted in 15 percent of cases, and for the remainder manufacturers self-certification sufficed. In the EC, some 75 percent of the value of intra-EU trade in goods is subject to mandatory technical regulations. As a result, the impact on firms operating in the most concerned sectors can be huge: redundant testing and conformity assessment procedures faced by Hewlett-Packard increased six-fold over the years 1990-1997. Similar observations can be done for the other TF component -- customs procedures. The average customs clearance transaction in developing countries involves 25 to 30 different parties, 40 documents, 200 data elements, some 30 of which are requested at least 30 times, and 60 to 70 percent of which must be re-keyed at least once [Roy, 1998]. Increasingly numerous and complex TRS, and customs procedures and requirements generate substantial costs. These costs have been estimated in the EC equivalent to a “tax” of up to 2 percent of the value of the goods shipped. In a developing country environment, they can be a multiple of this. For instance, Egyptian customs clearance practices in the early 1990s were characterized by extensive “red tape” and many goods were subject to redundant testing and idiosyncratic standards -- the latter being equivalent to between 5 and 90 percent of the value of the goods [Hoekman, 1998]. 2 The remainder of this Section draws on Hoekman (1998). 3 1.1. The trade coverage of TRS: a differentiated impact? Almost all the above figures are global. They are silent on whether TF-related costs are relatively uniformly spread over all the trading partners of a country, or whether they tend to hurt more certain countries than others. Differentiated effects can flow from various sources: certain products are more subject to TRS than others; bilateral or regional agreements on common TRS could result in discrimination and trade distortions -- both between members of the agreement (in this respect, common TRS are analyzed as potentially similar to endogeneous tariff formation in the context of a free trade zone, hence favoring the dominant industry of the zone [Olarreaga and Soloaga, 1998]) and between members and non-members (in this respect, common TRS are analyzed as potentially equivalent a common external tariff leading to trade-creation and trade-distortion effects between a customs union and the rest of the world).3/ What follows aims at providing a sense of the magnitude of a possible differentiated impact (based on the EC experience for which there has been an effort to collect systematic data on the TRS coverage by sector). Table 1 is based on information published by the European Commission [Single Market Review, III.1, 1998]. The two first columns provide crude estimates of the sectoral value-added covered by EC efforts either to harmonize Member state TRS (substituting European TRS to Member state regulations) or to promote the mutual recognition of Member state TRS by each other (around a minimal core of European common regulations). The sum of the two columns by line does not necessarily add up to 100 percent (some products are still subject to no Member state nor EC TRS). The third column provides an “index of failure” of the EC efforts for eliminating TRS-related trade barriers within the EC. This index ranges from 1 (EC efforts have been relatively successful at eliminating intra-EC TRS-related barriers) to 2 (success is mixed) and 3 (serious problems remain). The EC average index of failure is roughly 1.5, but sectoral indices vary substantially. The last column recapitulates the rates of global protection (adding up tariffs, non-tariffs barriers and antidumping measures) on goods imported by the EC from the rest of the world [Messerlin, 1999]. Table 1 provides two main results (all related to manufacturing only). First, sectors dominated by the harmonization process per se (more than 50 percent of the sector is covered by harmonizrd TRS) represent 33 percent of EC value added, 35 % of intra-EC trade, but only 22 % of EC imports from the rest of world. This differential could reflect a possible discriminatory effect (among other factors) of the EC harmonization on extra-EC trade, all the more because they are concentrated in sectors where there are high rates of EC global protection.4/ Differences between the EC trading partners can be substantial: if these sectors /Harmonization ( the EC “Old Approach,” see below) can generate internal and external distortions, whereas mutual recognition (the EC “New Approach,” see below) seems more limited to distortions between members and non-members. 3 /Any EC TRS Directive has two possible effects on extra-EC trade: (i) it can reduce it to the extent that, in addition to some perfectly respectable economic purposes, it includes a protectionist element which creates an additional extra-EC trade barrier; and (ii) it can be a source of trade diversion to the extent that it is a successful instrument of intra-EC trade 4 4 represent 22-26 % of EC imports from the U.S., Japan, and Central European countries, they represent 14% and 29% for EC imports from the emerging countries (Hong Kong, Korea, Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, Taiwan and Thailand) and from ACP countries, respectively. Combining high coverage by the harmonization method and a low (close to 1) index of failure (meaning that the adoption of EC TRS has succeeded) may be a particularly dangerous combination for non-EC countries: it maximizes the likelyhood of extra-EC protection with intra-EC trade diversion (from the success of creating European TRS). This mix is observed in mining (mostly energy), paper, and transport equipment: it represents 21 % of intra-EC trade and 13 % of EC imports from the world, with again a differentiated impact on EC trading partners (substantial for the U.S. and Japan, more limited for the three other groups of trading partners). The second group of results is related to sectors with high indices of failure of the EC TRS policy. These sectors with an index higher than the average represent 62 % of intra-EC trade and 69 % of EC imports from the world, suggesting that things are slow to change (except, possibly, for the Central European countries). Sectors with an index of failure larger than 2 are much smaller: 35 % of intra-EC trade, 32 % of EC imports from the world, with a large difference between Japan (relatively unconcerned) and ACP countries (relatively protected by the ineffectiveness of the EC TRS policy). 1.2. Trade Facilitation and WTO Dispute Settlement Cases Both components of trade facilitation (TRS and customs procedures) have emerged as one of the recurrent theme in WTO dispute settlement cases. Cases raised by customs procedures have involved customs classification, duty collection, GSP coverage, quota management and import measures. Cases raised by TRS are even more numerous: cases on tunas and dolphins, shrimps and turtles, beef hormones, and on asbestos focus on this topic, but provisions from the Uruguay TBT Agreement is invoked in many other complaints. All these cases have involved industrial and developing countries, both as complainants and defendants. These cases have had (so far) a very different fate, depending whether customs procedures or TRS are at stake. Cases on customs procedures have been kept at their technical level, terminated without too many fights, and are (so far) followed by compliance of the loosing party (or, at least, an official statement to comply). In sharp contrast, cases involving TRS have generated a lot of emotion and heat, and compliance to panel rulings seems far to be automatic (in particular since the EC decision not to implement the beef hormone WTO ruling). The first lesson to be drawn from these four years of cases is that the approach used by the WTO (which is similar to the approach used internally by WTO Member states) does not provide the robust guidelines necessary for a satisfactory handling of dispute settlement cases. The WTO approach relies on scientific expertise, in accordance with many of its liberalization. 5 provisions (for instance, Article 1.1 of the Uruguay TBT Agreement). This reliance leads to two typical situations. In the first situation, the scientific community is unable to assess risks -- a not so rare situation, particularly for technologies lacking the data necessary for risk assessment because evidence has to be found ex post (asbestos) or because new technologies are involved (genetically modified organisms or GMOs). In the second possible situation, the scientific community largely agrees (inocuous beef hormones) but governments captured by vested interests (or simply by their inability to act) blauntly dismiss scientific evidence.5/ This WTO problem with scientific evidence is compounded by the fact that, almost by definition, trade conflicts are likely to arise in these two situations -- the first one being highly correlated with the emergence of a more efficient (maybe more costly in the long run) production pattern, the second one with a typically protectionist behavior. Again, these problems are not specific to the WTO. In North America, an additive to gas for cars (methylcyclopentadienyl manganese tricarbonyl, or MMT) has been banned on health grounds by the U.S. EPA, but not by Health Canada -- fueling one of the most bitter disputes in Canada-U.S. trade. In the EC, Finland (which produces cadmium-free phosphates) believes that cadmium in phosphate is damaging for health in the long run, whereas Spain or Italy (which import cheap phosphates with a relatively high cadmium content from Morocco) do not. Such examples abound. But the additional problem for the WTO is that it relies on a strict de jure consensus between Member states -- increasingly complicated with a de facto consensus between people because of NGO-driven medias. Two actions could be envisaged by the WTO for making more robust the scientific support it depends on more critically than WTO Member states. The first is to put into a perspective the dispute settlement cases. The fact that medias report on a case by case basis is highly counter-productive: it exacerbates unrational feelings, and their easy capture by the vested interests. For instance, many Europeans (Americans) find acceptable (unacceptable) the EC ban on imports of beef hormones and unacceptable (acceptable) foreign prohibitions on EC exports of non-pasteurized cheeses (despite risks of salmonella). In order to reveal these many inconsistencies, information from the WTO on scientific summaries related to dispute settlement cases would be helpful. A second action would be a commitment by WTO Members to take domestic measures for educating their population on “risk management” in health and environment matters. In too many countries (including industrial), scientific committees are not trusted by the public opinion, and they are perceived as captured by their government or lobbies. Tightening cooperation between the WTO, UN Agencies in food and environment and top /The EC has banned the use of six hormones for cattle growth promoting purposes in 1988, after years of strong intra-EC conflicts. Few experts (including in Europe) believe in a serious health risk related to beef hormones. In fact, three of the six hormones are authorized in the EC for therapeutic uses, and there are constant rumors reporting a sizable illegal (growth promoting) use of all these hormones in the EC. The ban is deeply related to the depressed situation of the beef market and the unability to reform the CAP (hormones can increase beef production by 20 percent, meaning increased meat stocks under unchanged CAP rules. 5 6 scientists would be a way to enhance the reputation of world-based scientific committees, and to stabilize public opinion. 2. The top-down approach : TRS Eliminating differences between TRS seems a priori the best way to eliminate TRSrelated trade conflicts. This “top-down” approach has been chosen by the EC, but it has proven to be a mitigated success (as implicitly suggested by the many indexes of failure higher than 1 or 1.5 in Table 1). What follows suggests that a government-based top-down approach in the WTO context would be also costly -- but that private initiatives (possibly supported by public actions) would be useful. TRS can be “produced” in two ways. They can rely on mandatory public norms (the “TR” side of TRS), defined by governments or public agencies more or less actively backed by scientific committees (with the above-mentioned credibility problems). At the other end of the spectrum, TRS can be defined by firms, or groups of firms (the “S” side of TRS), which are then seen as the only economic operators knowledgeable enough for mastering adequatly the problems raised by technical progress: firms are left free to develop their own appropriate standards (eventually to monitor them with the necessary disciplines) in which they invest their own credibility (loose standards would damage the firm's reputation and profits). Firms can act collectively: the fact that TRS can require collective action does not necessarily imply that they require state or public actions. All these distinctions are particularly important in the WTO for several reasons. First, WTO Members are very different in terms of the proportion of the two sources of TRS: a TRbased mix remains largely dominant in many former centrally-planned economies and developing countries, whereas a S-based mix emerges as an important force in developed market economies -- except for health and environment related issues (an important exception, since, at noted in the introduction, these topics are particularly conflictual in trade matters). This remark is reinforced by the fact that some WTO Members, such as the U.S., are largely impermeable to this concept. Second, these two approaches have a quite different potential impact on trade. Although no general rule can be suggested, it seems reasonable to assume that the deeper the involvment of public authorities is, the more likely the protectionist and discriminatory impact of TRS could be. This hypothesis does not mean that firms-based standards have no protectionist or discriminatory content (they do, maybe even more than mandatory standards designed by public authorities). The justification of the hypothesis relies rather on the firms’ unability to enforce trade barriers in the long run without the help of public authorities. If this hypothesis is correct, it suggests that the deeper the involvment of public authorities is, the more likely trade conflicts could emerge. 2.1. Harmonization Table 2 aims at clarifying the WTO options by describing the four different basic 7 steps of a typical TRS policy: design, notification, enforcement of the TRS before the product reaches the market (a step which covers the many operations related to conformity assessment) and finally enforcement of the TRS once the product is available on the market in order to eliminate fraud (market surveillance). The first column presents the main GATT Articles or related textes refering to these various steps. The three other columns presents a brief summary of the progressive construction of the EC TRS regime (seen as an interesting illustration since the EC is a deeply integrated region). During its first 25 first years (1958-1985), the Community has aimed at harmonizing the pre-existing Member state TRS (the so-called “Old Approach” illustrated in column 2) by adopting “European norms” proposed by the Commission and negotiated by the Member States in the Council of Ministers. Adopting Directives based on full harmonization required, on average, two to three years (up to eleven years in the case of the “Mineral water” Directive) because the unanimity rule was necessary at the Council of Ministers (en passant, this condition would also be required at the WTO), and because the technical work was devoted to the Commission which was barely prepared and equiped for handling it. As a result, only 3 EC TRS Directives were adopted in 1969, despite the growing number of TRS adopted by Member states and of the increasing impression that they restricted intra-EC trade. In the 1970s and early 1980s, the EC tried to break this deadlock by reducing the scope of harmonization through several options: (i) optional harmonization (a producer has the choice between EC harmonized rules or national rules -- but goods traded across borders will have to meet EC harmonized standards or the standards of the destination country); (ii) partial harmonization (harmonized rules apply only for cross-border transactions); (iii) minimal harmonization (Member states may add more stringent rules to the EC harmonized rules); (iv) alternative harmonization (the Directives provide alternative harmonization schemes for achieving the objective pursued); and (v) piecemal harmonization (each aspect or input of a product is harmonized separatly: for instance, car tyres, manometers for car tyres and auto glass are subject to separate Directives of harmonization). Following these efforts, a much larger number of Directives (222 between 1969 and 1986) was adopted, but at two high costs. First, the product coverage of these Directives is very narrow, often a consequence of piecemal harmonization. Second, most of these Directives have been drafted in extremely detailed manner -- hence requiring frequent and substantial redrafting (still ongoing today) which is a source of permanent conflicts (it offers permanent incentives to Member states to renegotiate past Directives). For instance, one of the first Old Approach Directives adopted (Directive 71/320) which deals with “braking devices on certain categories of motor vehicles and of their trailers” has been revised eight times, and its last version is 146-page long and intertwined with another Directive (Directive 70/156) which exhibits the same complexity (in 1997, there were 201 vehicle-related Directives). By contrast, harmonization at the world level could be better promoted by firms or regulatory bodies which can develop enough technical competence and prestige that they 8 could generate worldwide harmonization in their sector of competence. Some of these bodies could be inheritated from the inter-governmental “system of conferences” or “congresses” of the late XIXth century and early 1900s through which governments sought to address issues that had cross-border dimensions -- more than 30 intergovernmental organizations from mail (1863) to aerial navigation (1910). For instance, the International Telecommunications Union (ITU) eliminated the need for telegrams to be printed at each border post, walked across, and retyped by requiring international interconnection. After declining in importance during the interwar period, intergovernmental organizations again proliferated after the Second -expanding to new fields (such as labor markets, with ILO, or banking supervision rules, with the BIS) but with, as the primary area for cooperation, the same goal of establishing standards for products (services) and producers, and their enforcement [Hoekman, 1998]. Since the Second World War, a few regulatory bodies have had a worldwide influence, even if coming from one country, as best illustrated by the U.S. Federal Aviation Authority about aircraft safety during the 1970s and the 1980s. Today, these rare cases could expand to more complex situations, based on a mix of worldwide firms’ and public agency’s reputations (and the high costs associated to reputation loss, such as the ValueJet case). Another source of worldwide TRS is collective efforts from enterprises. For instance, international railway unions promoted the establishment of networks by adopting the same rail gauge, standardizing rolling equipement, driving on the left, and adjusting signals, brakes and timetables to each other. Interestingly, these inter-firm agreements tend to have spillovers on related services, such as negotiated agreements on companies’ use of each other’s rolling stock, on the mutual repair and cleaning of freight cars, on the adoption of a single bill of lading (a single document could be used for all trans-European shipments), and they could culminate into trade liberalization, such as abolishing transit duties on goods shipped by rail [Hoekman, 1998]. These examples suggest that firms can achieve more easily wider cooperation than governments. However, it is also fair to raise the possibility that they generate market dominance for the initiating firms (which is not a problem) and its potential abuse (which is). An illustration of these concerns is the inter-war efforts by steelmakers from Belgium, the Netherlands, France and Germany to use “freight rates, terminal charges, and complex systems for documentation and classifying raw materials and finished goods to favor their own producers, ports, cities or transfer points” [Murphy, 1994, p. 109]. These efforts for reducing intra-European TRS were clearly aiming at consolidating at the European level the efforts to cartelize national European steel industries. The collusion issue is often raised as an argument dismissing the benefits from collective efforts by firms for designing TRS, or as an argument for substituting public efforts to private initiatives. Both arguments are not convincing. As underlined above, public efforts to design worldwide (or plurilateral) TRS are less likely to succeed and/or to survive: governments are less flexible than firms, less willing to take into account consumers’ requests (and to revise their plans accordingly) and more easily captured by the most extreme vested interests (so that they are often at the roots of conflicts which could have been solved more 9 easily under firms’ management). Concerning the risks of collusive behavior, they exist of course. But governments have the necessary instruments to discipline them (when they do not reinforce them, a not so rare situation). In particular, competition authorities have enough muscles (if they are “free” enough) to discipline most of the risks of such collusive behavior. For instance, all these aspects seem present in the GMOs issue. Public intervention in this source of tensions has not simplified or made less conflictual the issue (on the contrary). In sharp contrast, certain U.S. and EC firms have recently started to build their reputation on the absence of GMOs inputs. Farmers are waving consumers’ interests, but in fact, they are concerned by their own direct interests: GMOs are likely to increase the quasi-vertical integration links between farmers and GMO producers, at a time when farmers feel too much integrated to retailers for other farm products -- all difficult issues in terms of competition policy. 2.2. Notification The failure of the Old Approach by the EC was made more visible by the adoption by Member States of a considerable amount of domestic new TRS. In 1983, the Commission tried to stop this increasing divergence by imposing a notification process (under Directive 83/189) whenever a Member state was considering the adoption of new technical regulations. In addition to its monitoring function, the Directive allows for standstill arrangements and for proposals of EC TRS (instead of Member state TRS) whenever the Commission believed that the proposed national legislation would generate new technical barriers. Notifications are examined by a Committee 83/189, formed of high level officials from Member states and from the Commission. Notifications revealing possible conflicts between EC and national TRS are sent for comments to the concerned bodies of each Member state (Ministries and Member State Standard Bodies) and of the Community (the Commission and European Standard Bodies). Comments can lead to “observations” and, in case of possible infringement to Community law, to “detailed opinions” suggesting Community measures in order to eliminate conflicts. During most of the 1980s, Directive 83/189 has had a limited impact. Since the early 1990s, it has played an increasingly important role for several reasons: the recourse to “mutual recognition” (see below, “New Approach”) which offered an alternative to deadlocks on harmonization; the expansion of its coverage to key sectors (food products, pharmaceuticals and cosmetics) and to EFTA countries (large producers of TRS-intensive goods, and eager to keep EC markets open); and the relatively easy access of EC firms to the procedure. Since the mid-1990s, the 83/189 Committee examines between 430 and 470 new regulations each year. If many notifications are effectively done by Member states, there are a substantial number of cross-notifications or firms’ complaints. Out of all these 430-470 annual notifications, 75% have raised observations and 40% “detailed opinions.” However, actions have been taken only in a very small number of cases (2 percent). The 1994 Uruguay Round has introduced three measures in favor of notification of TRS: (i) the creation of an “enquiry point” in each WTO Member [TBT Agreement, Article 10 10], (ii) the creation of a WTO standards information system (Ministerial Decision on Proposed Understanding on WTO-ISO Standards Information System) and the regular review of the notification requirement by WTO Members (Ministerial Decision on Review of the ISO/IEC Information Centre Publication). However, these measures are far to meet the major reasons for the (relative) success of the Committee 83/189: in particular, there is no institution equivalent to the Commission which could discuss proposed TRS in the same room that Member’s delegates, and there is no easy access of firms to the WTO procedure. In this context, the only useful improvement would be to open to firms access to WTO notifications. This type of proposal is not very palatable to such a government-driven institution as WTO. However, it should be possible to find, through institutions such as the International Chamber of Commerce, a forum where firms’ rights could be exercised, and then sent to the WTO for information. 2.3. Mutual recognition After the limited success of harmonization and notification, the EC introduced the notion of “mutual recognition” at the level of the design of TRS. This so-called “New Approach” consists in limiting harmonization to the minimum core of technical aspects (the “essential requirements” which could also be optional, partial, minimal, etc.) and in ensuring the mutual recognition of existing Member state TRS for all the other aspects of the TRS examined. This approach looks flexible enough to be an interesting solution in the WTO contexte. However, the New Approach has required three conditions in the EC which are not met at the WTO. Moreover, its success requires a word of caution: its implementation is very recent, and its (unweighted) average index of failure is 1.4 -- not very mcuh different from 1.6 for the Old Approach. First, the New Approach has not been initiated by the Commission but by the Court of Justice in two landmark rulings (the 1974 Dassonville and the 1979 Cassis de Dijon rulings). The Commission could have initiated the New Approach on the basis of Article 30 of the Treaty of Rome which states that “quantitative restrictions on imports and all measures having equivalent effect shall [..] be prohibited between Member states:” defining TRSrelated trade barriers as such measures having equivalent effect was quite possible. But the Commission felt that it had not the political clout necessary for such an inititiative. The absence of a Commission and a Court, and a GATT Article XI weaker than Article 30 of the Treaty of Rome leaves a WTO approach in this direction in the fragile hands of a series of panel rulings going in the same direction and long enough to build a solid jurisprudence. This last condition will require at least a decade or two (it is useful to note that it took ten years after the Dassonville case and six years after the Cassis de Dijon ruling for the Commission to engulf the EC in the track open by the Court of Justice). Ultimatly, introducing the New Approach would require a firm commitment by the WTO Members, as it has been the case in the EC: the New Approach was definitively part of the EC only when a new Article 100 was introduced in the Maastricht version of the Treaty of Rome in order to give a robust legal basis for the mutual recognition principle in the field of the 11 “approximation of laws.” In particular, Article 100A introduced an innovation hard to imagine in the WTO context: the qualified majority vote in TRS matters. Second, the adoption of mutual recognition at the level of designing TRSs has also required an elaborate system of safeguards in the EC. No less than three “safeguard” clauses (Articles 36 and 100A:4, and the “rule of reason,” or “mandatory requirements,” included in the Cassis de Dijon ruling) counterbalance Articles 30 and 100A. The use of these safeguards is strictly limited by conditions imposed by the Court: (a) causality (for being prefered to EC TRS, Member state TRS must contribute directly to the policy objective); (b) proportionality (Member state TRS should not be more trade-restrictive that it is necessary for achieving the policy goals); and (c) the choice of the least trade-distorting instrument (the Member State shall choose the least trade-distorting instrument for achieving its fixed goals). Conditions (a) and (c) are hard to imagine in the WTO context. Moreover, the European Court of Justice recognizes the right to enforce Member State TRS in a few limited cases which include public health, consumer protection, and protection of the environmental or the working environment, that is, in all the topics which are at the heart of today’s most conflictual and difficult trade disputes. This right is often used by Member states, generating a continuous erosion of what has been achieved. All these legal difficulties should not hide a third, more profound, problem: the real efficacy of the New Approach. The EC expected that this Approach would lead to rapid and substantial progress. And indeed, the New Approach (based mostly on 28 Directives) covers a larger value added share than the Old Approach Directives (43% vs 33% of total industrial value added, as shown by Table 1), with much less time absorbed by their drafting and with a much simpler legal system (for instance, one Directive (89.392 on machines and lift machines) is estimated to cover 55,000 types of machines [Pelkmans and Egan, 1992]). However, there are signs of disappointment coming from three sources, all of them suggesting some caution for the WTO. First, the procedure for producing New Approach Directives has remained very complex. The Commission issues “mandates” to the European Standard Bodies (ESBs) by which it invites them to prepare “European standards” complying with the “essential requirements” the Commission defines in the Directives. Essential requirements have often been too vague to be useful, leading to unclear mandates for the technical work to be done by the ESBs (for instance, in the “Machine safety” and “Construction products” Directives, the Commission has been obliged to draft “interpretative documents” of its own essential requirements, making the process of defining European TRS again very slow and frustating). Second, creating operational standard bodies (SBs) has proven much more difficult than expected. The ESBs were not initially conceived for fulfilling the rôle of providers of TRS devolved to them by the New Approach. The three major ESBs (CEN, Comité européen de normalisation, CENELEC, Comité européen de normalisation électro-technique, and ETSI, European Telecommunications Standards Institute) were mere fora where Member state standards bodies could gather for implementing international standards drawn up by the international standard organizations (ISO) in an uniform manner in the EC. Lastly, and probably more deeply, it has been 12 progressively realized that the level of designing TRS Directives is only one aspect of a complete TRS regime: it leaves (and indeed can exacerbate) many pending problems at the enforcement level, as section 3 shows. Despite all these difficulties, mutual recognition at the level of designing TRS seem to be increasingly used at the regional level -- with the risk of discrimination against nonmembers of the regional agreements (see section 1). Regional experiences have a wide range: from the Trans-Tasman Mutual Recognition Arrangement (TTMRA) which covers all goods and services (except, medical practitioners) and which reduces to nothing the essential requirements (goods legally sold in one country can be sold in the other, and service providers registered in one country can practice in the other) to the much more limited NAFTA approach [Beviglia Zampetti, 1999]. A key point in such agreements is whether foreign products imported in one Member state could be exported to the other Member states without further formalities: this condition is likely to be respected in the case of a customs union (because it is felt required by the notion of a “single market,” as in the EC) but not necessarily in the case of free trade areas. In this context, it seems that the essential role for the WTO would be to ensure that this discrimination should be minimal -- by ensuring that the principles of open access and conditional MFN can be applied to third parties seeking to join the regional agreement [Messerlin 1996, Hoekman, 1998]. In particular, this condition requires that any country meeting the “essential requirements” should be able to participate to the TRS regional agreement. 3. Market surveillance at the borders: customs procedures Excessive control and inefficiency of customs clearance procedures, combined with the monopoly of service providers in the ports or other key entry points in importing countries, have been widely observed in many part of the developing world. Resulting costs can exceed tariffs in many cases. Documentary red tape in customs procedures increases the cost of imports substantially -- around 7-10 percent of the world trade according to Staples [1998]. Anecdotal evidence of administrative customs inefficiencies and of its impact in several developing countries is abundant. The average customs clearance transaction in countries of the Middle East and North Africa (e.g., Egypt, Jordan, Lebanon) requires 25 to 30 stages, and takes from one day to several weeks [Roy, 1998]. Valuation procedures are a major uncertainty on the part of importers, as Customs generally expects underinvoicing. It is the practice in some Middle East and North Africa countries that Customs officers question every invoice in order to charge penalties or collect “rewards” (for instance, in Jordan, the law rewards Customs officers who allegedly uncover invoice misreporting and charge penalties to the importers). An other related customs barrier to trade facilitation are the problems facing transport operators when crossing the frontiers. Transportation by road is an important cross-border mode of passenger and freight transport in many countries (in particular for the landlocked 13 countries in Africa and Latin America). The International Road Transport Union has reported that the most restrictive cross-border transportation can be found in some parts of Europe and the Middle East and North Africa [WTO Document, S/C/W/60]. The cost of delays that affects international trade is estimated to be about 6 percent of transport time in some countries of Central and Eastern Europe. Complaints from the transport profession mention also excessive charges that impair the freedom of transit contained in Article V of the GATT. The monoply of port services has led to inefficient regulation of port operations and has contributed to implicit tariffs of 5 to 15 percent on exports in Latin America [Guasch and Spiller, 1999]. The cost per ton of handling a container in the port of Alexandria (in Egypt) is reported to be a multiple of that in other Mediterranean countries [Hoekman, 1995]. The lack of competition in related services to trade (such as in insurance) has been translated into higher insurance premia charged for trade coverage, as compared to insurance charges facing Egypt's competitors in other regions. Unilateral reforms (often assisted by the IMF and the World Bank) have been initiated by many developing countries. They deal with national customs procedures and regulatory requirements imposed by other agencies on cross-border trade, and they aim at ensuring an efficiency mix in revenue collection and trade facilitation following a set of guidelines covering best practices developed in particular countries and customs administrations. A number of developing country members of the WTO have stepped up efforts to improve inspection and clearance activities in anticipation of the full implementation of the WTO Agreements which have a direct relation to trade facilitation. Many others need longer transition periods with regards to the implementation of parts of the Agreements (Egypt has already asked for an extended period of three years to implement the Agreement on customs valuation). The same trends of restructuring and reform have been taking place for port services through privatization and government relinquishing to the private sector the lease and management of public port facilities. In this context, multilateral initiatives are particularly useful for generating guidelines based on best practices, and for accelerating reforms. Following the many Uruguay Agreements that have implications for customs procedures (Customs Valuation, Import Licensing Procedures, Preshipment Inspection, Rules of Origin, Technical Barriers to Trade and Sanitary and Phytosanitary Measures) the 1996 Singapore Ministerial Declaration added trade facilitation to the WTO agenda, and held a Symposium on Trade Facilitation in December 1997.6/ The following main obstacles related to customs procedures have been listed: excessive documentation requirements, lack of automation and low use of information technology, lack of transparency in import and export requirements, lack of use of risk assessment techniques and audit-based controls and lack of cooperation among customs and other governments agencies. A report is to be submitted to the next Ministerial Conference evaluating the exploratory and analytical work to assess the scope for the WTO rules in the area of trade facilitation. /UNCTAD has contributed to this effort, most ntoably with the UNCTAD Trade Efficiency Symposium. 6 14 The basic guidance for customs administrations as regards customs procedures remains the WCO’s international Convention on the Simplification and Harmonization of Customs Procedures, known as the Kyoto Convention. The latter comprises a set of principles and 31 Annexes that lays out standards and recommended best practices for Customs procedures or arrangements. The Kyoto Convention has not been a successful multilateral instruments since it was drawn up in the 1973, because of its non-binding nature and the many outdated Annexes that do not reflect latest techniques and developments such as risk assessment, audit-based systems of control and automated systems. As a result, the Kyoto Convention has been under revision to reflect these points, and to become a comprehensive set of customs best procedures covering imports and exports, transit and warehousing. Expected major changes to the current Convention include a set of guideline drawn from best practices with specific examples from particular countries and customs administrations to assist other countries with available successful experience. Enforcing the revised Kyoto Convention will require a lot of efforts (and funds), in particular for valuation and enforcement training, and for developing contacts with the business and trade community in developing countries (customs’ partners should learn and understand all the new requirements and procedures). The key issue is whether the revised Kyoto Convention would be binding, or not. The Kyoto Convention is above all a set of customs best practices that is subject to technological changes. The WCO being in close cooperation with the Customs administrations around the world is the appropriate institution to oversee and enforce the Kyoto Convention. Nonetheless, enforcing a set of applying procedures would need a “dispute settlement” mechanism. The WTO as a rule-making institution might extent its “dispute settlement” mechanism to enforce the Kyoto Convention. Some WTO members have argued that the WTO should not be used to ensure enforcement of an instrument that was developed by another organization. A counterargument to this view is that the WTO has a mandate to achieve greater coherence in global economic policy making by cooperating with other international organizations. The WTO members have already given the WCO the responsibility for developing the rules of origin for non-preferential trade, in addition to the responsibility for promoting the WTO Agreement on Customs Valuations (including technical assistance to those countries in transition from the old GATT valuation system). A WCO/WTO cooperation in enforcing a new Kyoto Convention will mean that customs administrations in all the WTO members are operating from the same rules which is a further facilitative measure for the international business community. A way to get the benefits from the WTO/WCO cooperation and to appease the fears associated to the use of the WTO as an enforcing stick would be to negotiate a “restricted” list of international organizations with which the WTO could have deeper and more institutional relations. The list could start with one item in the coming Round -- the WCO -- but it could be subject to review in every Round. 15 4. The bottom-up approach : Enforcement Table 3 shows two “bottom” levels in trade facilitation: conformity assessment procedures (CAPs), such as testing, certification, marking, etc., which ensure that, before being sold, products comply with country’s TRS; and market surveillance (which includes customs procedures and requirements) which aims at ensuring that all the products available on its domestic market are conform to country’s TRS. As is well known, harmonized or mutually recognized TRS still impose a burden on trade if traded products or services are subject to CAPs in both the exporting and importing countries, or if they are subject to severe constraints on their choice of CAP units (either there are too few CAP units available, what is equivalent to a quantitative restriction, or enough CAP units are available, but at higher transport or transaction costs). Similarly, excessive customs procedures and requirements impose additional costs by requiring firms to spend unproductive resources from which no benefits are derived. These observations suggest an important corollary: the huge efforts invested in a “top-down” approach to the TRS issue (focusing on harmonization or mutual recognition at the level of design of TRS) can be a waste of resources if serious pending problems are left at the two bottom levels. This optimal balance between a “top-down” and a “bottom-up” approach is one of the most important TF issues, as illustrated by the EC. On the one hand, the ongoing discussions between the EC and the Central European countries (CECs) have generated a fear in the EC that CECs will not meet the level of competence at the CAP level desirable for implementing EC TRS, and will endanger the whole system. On the other hand, the negotiations and signatures of 58 MRAs at the CAP level between the EC and its major industrial trading partners [WTO TPR, 1997, p.139] seems an approach with large net benefits. Both observations suggest the bottom-up approach as the most necessary (for CECs and developing countries) and the most profitable (for industrial countries). 4.1.Conformity Assessment Procedures (CAPs) As said above, CAPs deserve attention because they can channel protectionist actions of their own. They cover a wide range of procedures -- from confidence in private behavior (manufacturers have strong interests to take care of their reputation which is an essential part of the firm’s capital) to reliance on ad hoc public agencies. Recognizing this range of procedures is essential in an open trade context because, as suggested in the introduction, the heaviest reliance on public intervention is, the easiest protectionist actions can be. It happens that in most WTO Members, CAPs traditionally rely mostly on state-related agencies. CAPs are performed by specialized units of all kinds (laboratories, public agencies, private firms) which constitute the core of a TRS “industry” which is relatively large in industrial countries: for instance, enforcing the 80,000 TRS existing in the whole EC requires 10,000 independent CAP units employing 200,000 workers, and having a turnover of ECU 10-11 billion (these estimates date from the mid-1990s). Regulating the CAP units is thus a crucial component of any TRS policy. In fact, the 16 huge increase of TRS-related activities in many countries requires to consider this services industry in the same perspective than it has routinely been done for the telecom or banking industries: the growth of the industry, its expanding scope of activities and its new requirements in terms of competence and technology require domestic regulatory reforms to be coupled with progressive liberalization. The condition of domestic regulatory reforms is well illustrated by the EC case. Most of the problems raised by CAPs converge to one point: the level of technical competence and ethical behavior required from the CAP units which is increasingly necessary in all the possible situations to be faced by CAPS. For instance, Table 3 illustrates the fourteen basic “modules” of CAPs existing in the EC for taking into account the nature of the product, the stage and type of the production process, the kinds of risks involved. For each of these modules, a EC Decision adopted in 1993 defines, in general terms, the tasks to be done, the operators in charge (manufacturer or CAP units) and the sharing of their responsibilities.7/ But each of the Directives imposing TRS on a given product selects the modules effectively open to the manufacturer (or importer) and to the CAP units, and can require that Member States “notify” and “accreditate” the CAP units (called the “Notified Bodies,” or NBs) that they declare competent to carry out the CAP activities for the group of products covered by the Directive in question. These 600 NBs (compared to the total of 10,000 EC CAP units) have thus a pivotal role: the technically correct and economically sound implementation of the whole New Approach depends from the competence of a relatively small number of organizations. But, in a recent survey (1996), the Commission found that the “accreditation” of NBs by Member states obeys to such a wide range of rules, methods and procedures -- or rather an absence of rules, methods and procedures -- that it represents a threat to the credibility of the EC TRS regime. This conclusion has induced the Commission to table several proposals for “harmonizing” accreditation procedures. It should be added that the problems raised by CAPs outside the scope of the New Approach are similar -- but made even more difficult by the wider range of CAP activities (not “limited” to 14 basic modules), by a larger number of available CAP units (10,000 units) and by a wider scope of CAP units (which range from the large organizations, such as SGS or Veritas, to small inhouse private units or to large government laboratories). In this wider context, the key issue is the recognition of the CAP unit chosen by a given manufacturer (often in its own country) or by its business partners (other producers, large retailers or distributors, or even consumers). In this context, what do domestic regulatory reforms mean? First, they would consist / For instance, under module "A-A" in Table 3, it is up to the manufacturer to declare the conformity of its product to the essential requirements listed in the appropriate Directive(s) and to the European standards established by the appropriate ESB. By contrast, the procedure under the module "B-F" is more complex: a CAP unit declares the conformity at the conception level of the product (with the necessary tests, if any) whereas, at the production level, the manufacturer is also involved for declaring the conformity of its product to its "type." 7 17 in introducing a healthy dose of competition between CAP units by allowing entry of foreign CAP units in domestic markets. Taking the EC case as an example, a CAP unit located in a Member state could decide to provide the “best” CAP services for only a limited range of goods -- those for which the agency believes to have the best expertise, that is, “comparative advantages” -- but for the whole EC.8/ If the “specialized” CAP unit has rightly assessed its abilities, it will attract manufacturers from the whole EC (not only those of its Member state of origin, as today). Second, regulatory reforms imply that conditions on ethical behavior (about the independence and qualification of the CAP unit staff, about confidentiality and traceability of the work done by the CAP unit, etc.) will be met. Presumably, these conditions are likely to be very similar across countries. Looking at TRS enforcement as an industrial activity, to be subject to domestic regulatory reforms combined with opening to foreign competition, makes this level of a TRS policy well fit to WTO activities: fundamentally, it assimilates the CAP level to a case for service liberalization. Such an approach can be adopted on an unilateral basis (as it has been the case in certain services and countries), as illustrated by the International Conformity Certification Program (ICCP) elaborated by the Saudi Arabian Standards Organization (SASO), the primary agency responsible for CAPs in Saudi Arabia. SASO Program has been a pilot conformity assessment procedure in developing countries that rely on the private sector to inspect shipments for compliance verification in the exporting countries. The ICCP is a combined conformity assessment, preshipment inspection and certification scheme to regulate and monitor shipments of selected categories of products prior to their leaving their ports of exports before reaching Saudi Arabia (the Program currently applies to 76 products categories divided into five groups: food and agriculture, electronics and electrical products, automobile and related products, chemical products, and others). The key element of the SASO Program is that each shipment must provide evidence of conformity to SASO standards (or their approved equivalents) before the certificate of conformity (required for every consignment) can be issued, and ensure both exporters and importers of a streamlined customs process which allows goods to clear faster and to face a minimum rejection risk at the port of entry. So far SASO Program has not been a complete success: it is considered as a costly process by traders in major trading partners to Saudi Arabia (complaints have been related to high fees payed for obtaining certificates of conformity, and to the high strorage fees, as each consignment has to be isolated in storage during the testing stage). But the interesting aspect of the SASO Program is that test data can be produced by nationally or internationally accredited laboratories approved by SASO, or by the manufacturer’s declaration of conformity. At the conclusion of the SASO approved laboratory testing, a Conformity Test and Evaluation Report is issued and submitted to the /En passant, this alternative is much more consistent (in sharp contrast with an increasing grip policy) with the popular view in the EC according to which the New Approach and MRAs are a way to promote competition between rules and between regulators. 8 18 Regional Licensing Center for verification of Conformity to SASO Program Requirements. SASO Program closely follow ISO/IEC Guide 28 (General Rules for a Model Third Party Certification System for products), particularly with regards certain products that have achieved full compliance with Saudi standards. These products qualify for Type Approval License that allows their imports with the minimum of intervention. A key aspect of the SASO Program is that SASO has contracted an international firm to carry out these activities. This firm is in turn assisted by a network of accredited testing laboratories and inspection bodies around the round. The SASO experience shows that compliance verification of national standards might be better and cost-effectively served through mutual recognized agreements that will improve the certification time and reduce the induced cost for exporters. Many existing MRAs about CAPs signed by WTO Members are more limited: they do not generate a worldwide web of CAP units, and they aim more at eliminating excess costs from duplicate CAPs or from artificial constraints on CAPs than at reducing costs by increasing the competitive conditions on the market of CAP activities. In this context, the WTO should work in two directions. First, as for MRAs at the level of TRS design, the WTO should ensure that MRAs on CAPs do not distort trade by favoring MRA signatories at the detriment of non-signatories: as in section 2, this goal could be achieved by establishing clear “essential requirements,” the fulfilment of which would be an automatic passport to be a signatory of the MRA in question. If this condition is met, there should be few concerns about the burgeoning of bilateral and regional MRAs (in fact, the European Accreditation of Certification Bodies (EAC) in 1990 and to the European Cooperation for Accreditation of Laboratories (EAL) in 1994 have been prepared by a series of bilateral MRAs, such as those signed by France, the Netherlands and Sweden in the early 1980s). Second, the WTO should be the place to discuss CAP issues within the global framework of service liberalization with, ultimatly, exchanges of concessions on market access for CAP units.9/ At the beginning, this liberalization may be limited to industrial countries, because many developing countries still do not accept test data or product certifications issued through foreign laboratories and firms (foreign laboratories are allegedly not competent to serve domestic safety standards). However, increasing competition between CAP units from industrial countries may also enlarge the choice of developing countries about the foreign laboratories and firms that they could accreditate -- eroding their opposition. 4.2. Domestic market surveillance Ultimatly, the credibility of any TRS regime depends on its final impact on the markets -- that is, the fact that products and services on sale follow legal TRS. In order to /The proposal of an “APEC-wide Recognition of Product Certification,” based on an “APEC Laboratory Recongition Center,” is a regional variant of such an approach [Wilson, 1995]. 9 19 achieve these results, there are two main approaches -- one focusing on reputation and ex post penalties, the other one on ex ante surveillance of the markets by public agencies. An efficient functioning of CAP and market surveillance requires a delicate balance between reliance on manufacturers' reputation and credible actions from ad hoc quasi-public agencies. 5. Conclusion The paper has addressed trade facilitiation issues at large -- that is, covering technical regulations and standards (TRS) and customs procedures and requirements. All these issues are increasingly the source of trade conflicts, particularly acrimonious and damaging for the world trade system when they concern health and environment issues. The paper makes negative and positive proposals. If eliminating differences between TRS seems a priori the best way to eliminate TRS-related trade conflicts, this “top-down” approach has proven to be very costly in time and efforts, and ultimatly a limited success, as illustrated by the EC experience. There is no reason to believe that the same conclusion should not be reached at the world level, all the more because “scientific” evidence has proven a poor support for the WTO (and a poor protection in case of disputes between WTO Members). However, private initiatives in this domain (possibly supported by public actions, and checked by competition policy) have been numerous and often successful. In the context of enforcing existing TRS, the perspectives for direct WTO work are much better. First, the WTO should ensure that bilateral or regional agreements in these matters (the so-called mutual recognition agreements, or MRAs) do not distort trade by favoring the MRA signatories at the detriment of non-signatories: this goal could be achieved by establishing clear “essential requirements,” the fulfilment of which would be an automatic passport to become a signatory of the MRA in question. Second, the enforcement issues related to TRS (and, to a lesser extent, customs formalities) should be discussed in the global framework of service liberalization: increased competition between the agencies, firms and institutions in charge of conformity assessment would be beneficial. Such an increased competition would flow from domestic regulatory reforms leading to trade liberalization -- a process that is increasingly driving the WTO negotiations in services. Lastly, in the area of customs procedures, the enforcement of the revised Kyoto Convention on customs best practices needs better coordination between the WCO and the WTO, which might extend to the ability of invoking WTO dispute settlement mechanisms. 20 References Beviglia Zampetti, Americo, 1999, Market Access through Mutual Recognition: The Promise and Limits of GATS Article VII (Recognition), mimeo, World Services Congress, Washington. Guasch, J. Luis and Pablo Spiller, 1999, “Managing the Regulatory Process: Design, Concepts, Issues, and the Latin America and the Caribbean Story,” The World Bank Institute, Washington, DC. Hoekman, Bernard, 1995, “The WTO, The EU and The Arab World: Trade Policy Priorities and Pitfalls,” Center for Economic Policy Research, Paper No. 1226. Hoekman, Bernard, 1998, “Beyond National Treatment: Integrating Domestic Policies,” mimeo, World Bank, Washington. Messerlin, Patrick A., 1996, A Transatlantic Free Trade Agenda on Non-tariff Barriers, in Bruce Stokes, Ed., Open for Business: Creating a Transatlantic Marketplace, Council on Foriegn Relations, New York. Messerlin, Patrick A., 1999, The Costs of Protection in Europe, Institute for International Economics, Washington. Olarreaga, Marcelo and Isidro Soloaga, 1998, Endogeneous Tariff Formation: The Case of Mercosur, Centre for Economic Policy Research, London. Saudi Arabian Standards Organization (SASO), 1998, “Conformity Certification Program: ICCP,” SASO Website, <http://www.saso.org/SERVICES/iccp.htm>. Staples, B.R., 1998, Trade Facilitation, Global Trade Negotiations Home Page, <http://www.worldbank.org/trade/>. United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), 1999, Preparing for Future Mulitlateral Trade Negotiations,” UNCTAD/ITCD/TSB/6, Geneva. Wilson, John, 1995, Standards and APEC: An Action Agenda, Institute for International Economics, Washington. World Trade Organization (WTO), 1998, “Checklist of Issues Raised During the WTO Trade Facilitation Symposium, Note by the Secretariat,” Document G/C/W/113, 20 April 1998, WTO Geneva. World Trade Organization (WTO), 1998, “WTO Trade Facilitation Symposium, 9-10 March 1998, Report by the Secretariat,” Document G/C/W/115, 28 May 1998, WTO, Geneva. World Trade Organization (WTO), 1998, Document S/C/W/62, WTO, Geneva. World Trade Organization (WTO), 1998, Document S/C/W/60, WTO, Geneva. 21 Table 1. EC TRS Directives and EC imports, by sector, 1995 EC TRS coverage [b] Manufactur ing sectors ISIC classificati on [a] Ha rm oni zati on [c] 200 311-312 313 321 322 323 331 341 351-352 353 354 355 361 369 371 381 382 383 384 385-390 Mining Agro-business Beverages and sugar Textiles Clothing Leather goods Wood and wood products Paper and paper products Chemicals Petroleum refineries Petroleum & coal products Rubber and rubber products Pottery, china, etc. Non-metallic products Iron & steel Metal products Machinery Electrical & electronic goods Transport equipment Other manufacturing goods All manufacturing 96 100 63 Mutual tion 81 54 79 * 11 18 73 sum 33 * Rate of "failure" global Intra-EC protect. imports World U.S. Japan CECs Emer- ACPs 0.4 5.8 3.2 3.6 2.3 0.4 1.9 4.7 14.7 1.5 0.8 3.7 0.3 1.9 6.9 3.1 14.0 10.0 15.6 5.3 2.4 3.8 1.1 4.2 5.6 1.0 2.2 2.5 9.2 1.6 8.5 2.1 0.6 1.0 7.1 2.2 16.5 13.5 8.3 6.7 [e] 2.5 2.1 0.9 1.2 0.6 0.2 1.4 3.7 14.1 0.7 0.0 2.3 0.3 0.7 3.7 1.7 29.0 18.2 11.4 5.5 [e] 0.0 0.1 0.1 0.9 0.2 0.0 0.0 0.5 9.1 0.0 0.1 2.7 0.0 0.9 0.8 1.3 32.4 25.5 22.4 3.1 [f] 1.8 6.6 0.6 10.3 16.6 0.9 6.9 1.8 6.7 2.5 0.6 2.4 0.8 3.8 9.9 5.2 5.8 8.1 6.8 2.0 ging [g] 0.6 3.5 0.6 8.2 10.2 1.0 3.8 0.8 3.4 0.2 0.0 3.3 0.0 0.7 0.6 2.9 23.5 25.1 4.8 6.7 5.1 8.4 9.5 3.9 1.9 1.4 4.7 0.0 3.0 0.3 34.8 0.1 4.2 0.0 7.7 0.1 0.6 0.5 5.7 8.0 25.8 22.9 74.0 15.9 22.5 10.4 53.9 22.6 13.8 6.2 77.0 18.2 29.1 10.8 71.0 63.8 recogni- 37 59 77 63 18 100 Index of 100 27 79 55 51 43 93 82 20 62 sum 43 [d] 1.2 2.0 2.0 0.9 1.5 (%) 3.4 30.4 22.5 23.1 31.4 1.3 1.4 2.7 1.0 2.9 2.4 1.6 2.5 1.5 1.0 1.9 1.8 0.9 2.1 avg 1.5 4.8 7.8 7.9 4.3 9.0 7.8 8.4 4.8 15.8 6.5 4.5 8.0 9.2 5.9 avg 13.7 EC trade Extra-EC imports from : All sectors with harmonization > 50% value added 78.4 12.0 1.6 12.2 34.9 21.8 23.5 harm. > 50% val.ad. and failure index < 1,50 77.5 6.6 1.2 6.8 20.6 13.3 17.6 index of failure > 1,50 23.9 62.9 2.1 12.8 61.9 68.5 73.6 index of failure > 2,00 35.1 51.5 2.4 12.6 35.3 32.3 25.6 Sources: The Single Market Review, 1997, Annexes. WTO TPR, 1997, p.139, Messerlin [1999]. Notes: [a] Based on a crude correspondance with NACE classification. [b] in % value added. [c] a "*" signals an important proportion of "mixed old approach." [d] see text. [e]: shade locates sectors with MRAs with the EC. [f] CECs: Central European countries. [g] Emerging: Emerging countries (see text). 1 Table 2. The basic elements of Trade Regulations and Standards GATT & WTO provisions Stages 1. Intensity of harmonization Who decides? 3. GATT, TBT Agreement WTO MSs Legal reference Who is responsable? Where? TBT Agreement WTO MSs Articles 30, 36, 100, 100A4 None "Essential requirements" None Commission & Council Commission & Council Member States SBs (at EC or MS level) SBs at MS level Directive 83/189 MSs/SBs Directive 83/189 MSs/SBs Directive 83/189 MSs/SBs Committee 83/189 Committee 83/189 Committee 83/189 Legal reference TCM procedures Rules on TCM units: TBT Agreement quality assurance NBs The "ten" basic modules NBs (600 units) The "ten" basic modules TCM units (10,000) mandatory EOTC mandatory (target EN45000) yes, EOTC voluntary EAC, EAL, GLP, EOTC no yes and Bilateral MRAs no Testing, certification and marking (TCM) CE marking Market surveillance A. B. Note: Articles 30 and 36 Full or "limited" Notification of TRS (a) accreditation (b)mutual recognition 4. No Harmonization Approach Adoption of TRS Legal reference 2. European Community Mutual Recognition ("New Approach") Harmonization ("Old Approach") Customs procedures Domestic monitoring (see text, Section 3.2) "SAD" MSAs MSs: Member states. MSAs: market surveillance authorities. NBs: notified bodies. SBs: Standardization bodies 2 MSAs MSAs