NORTH AMERICAN AGRICULTURAL POLICIES AND EFFECTS ON WESTERN HEMISPHERE MARKETS PRELIMINARY DRAFT

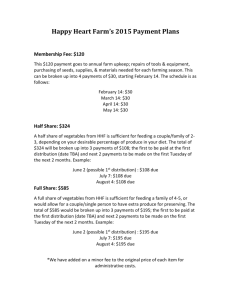

advertisement