Do the Rich Speak Louder?:

Examining whether U.S. Senators differentially respond to their

constituents by income across issues

by

Elisha W. Heaps

A.B. Government

Harvard University, 2010

SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF POLITICAL SCIENCE IN PARTIAL

FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIRMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF

MASTER OF SCIENCE IN POLITICAL SCIENCE

AT THE

MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY

1MASSACHUSETS

February 2014

INSTrUWE

OF TECHNOLOGY

MAY19 2014

LIBRARIES

@ 2014 Massachusetts Institute of Technology. All rights reserved.

Signature of Author

Department of Political' cience

October 31, 2013

Certified by

Christopher Warshaw

Assistant Professor of Political Science

Accepted by

Roger D. Peterson

Arthur and Ruth Sloan Professor of Political Science

Chairman, Graduate Program Committee

2

Do the Rich Speak Louder?:

Examining whether U.S. Senators differentially respond to their

constituents by income across issues

by

Elisha W. Heaps

Submitted to the Department of Political Science

on October 31, 2013, in partial fulfillment of the

requirements for the degree of

Master of Science in Political Science

Abstract

This thesis examines the relationship between public opinion and the way senators vote

on specific issues, and how this "responsiveness" might vary across income groups. The

independent variable of interest, state-level income group preference, is estimated using multilevel regression and poststratification (MRP) analysis. This is an improvement over earlier

methods, particularly when modeling income group level opinion where there are insufficient

sample sizes in national surveys. Income group opinions are found to be distinct across issue

areas and the top ten percent of the income bracket are found to hold different opinions when

compared to a more inclusively defined high-income group. Ideal point estimation is used

to generate the dependent variable of senator responsiveness based on roll call votes. The

first-stage MRP estimates of state-level income group opinion are then regressed on the corresponding senators' ideal points by issue area. While this paper expected the second stage

analysis to support an Instructed-delegate model of responsiveness, where senators vote in

accordance with constituents' interests, no evidence of such a relationship is found, even at

the aggregate opinion level. The evidence suggests that senators are looking elsewhere when

making their policy decisions.

Thesis Supervisor: Christopher Warshaw

Title: Assistant Professor of Political Science

3

4

Acknowledgments

This thesis would not have been possible without the support and encouragement of many

individuals. I cannot thank them enough for all of their help throughout this entire process.

First and foremost, I would like to thank my thesis supervisors, Professor Christopher Warshaw and Professor Adam Berinsky. Professor Warshaw generously spent many hours helping

me to apply MRP analysis, think through validation tests, develop modeling for the second

stage analysis, and construct a strong argument for my thesis. I was very fortunate to have

the opportunity to build on his own great accomplishments in the field. Professor Berinsky critically evaluated my work, which helped me develop a deeper understanding of the

topic and create well-formed methodological justifications for my modeling choices. It was

in Professor Berinsky's class that the idea for this project was born and, with his teaching,

I learned how to critically engage with the current scholarship and gained a more nuanced

understanding of the nature of public opinion and the challenges of using survey data. They

have both been true mentors and I owe them the greatest thanks.

I would also like to thank Professor Teppei Yamamoto who helped me apply the statistical methods used in this paper and provided me with a solid methodological background

in the classroom.

Chad Hazlett and Michael Sances, graduate students in the Political

Science Department, were both very generous with their time and I greatly appreciate all

of their help and advice. The comments and feedback from my cohort were also very helpful.

Finally, I would like to thank my family and friends for support, especially my husband,

Kevin. He provided me with advice, emotional support, and helped me locate the sources of

several pesky coding errors. He also helped to edit this Masters thesis, just as he had done

with my undergraduate honors thesis. I owe him my deepest and most heartfelt thanks.

5

Introduction

In this paper I examine the relationship between public opinion and the way senators vote

on specific issues, and how this "responsiveness" might vary across income groups. More

specifically, I will test the hypothesis that there is greater congruence between the way senators vote and the opinions of their higher-income constituents in certain policy areas (such

as economic policy), but not in others (such as social welfare). I first ask the question: do

constituents have opinions that vary by income level? I then test to see whether senators

are more responsive to a particular economic group when it comes to making policy for the

nation.

"Let them eat cake"

If the affluent have an oversized impact on the behavior of their elected officials scholars

should question what it means to have "true" democratic representation.

In the words of

V. 0. Key, "Unless mass views have some place in the shaping of policy, all the talk about

democracy is nonsense" (1961).

While we might not expect nor want a perfect correlation

between public opinion and government policy, enduring inequalities based on income status may be problematic for society. More privileged groups might try to shut out weaker

actors (perhaps by creating barriers to participation) in order to maintain their advantage,

undermining democracy (Schattschneider 1975). In any political conflict, the powerful seek

to privatize the issue to prevent the mobilization of the people, while the weak will try to

publicize the conflict so as to tip the balance of power. Government is an instrument of this

socialization of conflict.

Economic inequality has been increasing for the past thirty years in the United States.

This increase is compounded by the fact that responsiveness to the wealthy may have also

grown over this period (Gilens 2012, 252). Some argue this extreme concentration of income

gains at the top may in part be brought on by government policy perpetuating this "winner-

6

take-all" pattern (Hacker and Pierson 2010). This means influence is shifting toward a class

that looks increasingly dissimilar from the rest of America. If the wealthy have distinctive

preferences that are meaningfully different from those of other Americans, this may result

in a system of government that is not protecting the interests of the economic underclass.

The American representative republic is designed to protect and attend to the interests of

all citizens and as such, elite favoritism could pervert the government's purpose. While high

income individuals are generally more highly educated, they may lack information and experience to balance their views on public policy, or they may not care about advancing interests

other than their own. Therefore, first examining how the income preferences diverge and

then testing how they compare to their senators' votes will yield valuable insights about the

representative system.

Cacophony or Coherent?

One challenge to this line of inquiry is that the public may not have a clear opinion on

policy. If no clear opinion can be interpreted by the government, then the government cannot respond to it. Downs argues that it is rational to be ill-informed about public affairs,

conditional on trusting others to make decisions on one's behalf (1957). Lupia finds a solution to this problem of low information with the finding that people are able to form opinions

based on cues that would essentially match informed decision-making (1994). However, Lupia's work may be critiqued as only being the case for a small percentage of policies where

such cues are readily accessible to the public.

While Converse argues that individual opinion data is inconsistent and incoherent (1964),

Page and Shapiro show that in aggregate, public opinion is "stable and sensible" (1992, 1).

Fluctuations in opinion that might be observed at the individual level are absent when assessed en masse. Achen also responded to Converse's study and found that individuals' low

response stability was primarily due to measurement error (1975). While the empirical find-

7

ings of Converse's study have been scrutinized, he also suggests that most people structure

their thinking in terms of social groups. An income group may be one example of such a

reference group or an aggregation of related reference groups. Kinder expands on Converse's

reference and suggests that citizens first recognize the policy that benefits their group and

then form their opinions accordingly (2003). Dawson found that black Americans use group

identity to form policy preferences, which helps to explain why black party identification

is cohesive and relatively uniform (1994).

This suggests that it is possible to see distinct

preferences formed by income group either on the basis of membership within that particular

income group or because many readily identifiable subgroups can also be sorted into income

categories, such as a community church.

Only in rare cases are people be able to see the direct benefits of a policy to themselves, such

as the Vietnam War draft and Social Security benefits (Erikson and Stoker 2011; Campbell

2005). The received wisdom is that self-interest is not relevant in the formation of political

opinion (Sears et al. 1980). Therefore, while I would expect income group opinions to be

distinct and identifiable, they most likely formed from associations with people in a similar

income bracket.

Low-income individuals are more likely to belong to the same churches or bowling leagues

just as high-income individuals are more likely to frequent the same stores and belong to

the same country clubs. This sorting by income happens naturally, and as consequence,

different preferences concerning national policy are likely to emerge.

There are different

opinion-leaders in different social circles and it would be expected that these associations

simultaneously homogenize in-group preferences and perpetuate differences between groups.

Berelson, Lazarsfeld, and McPhee argue that political opinions are formed through the smallgroup contexts of friends, family, and coworkers and these groups tend to be homogeneous

in makeup (1954).

Expanding on this theory of social group opinion formation, Huckfeldt

and Sprague theorized that members of a political majority were less likely to recognize a

8

member of a political minority in their community (1987). If individuals fail to interact with

people from a different point of view or, if they are failing to recognize that they are doing so,

then it reasonable to expect that income group level differences to be real and self-sustaining.

When the People Talk, Does. Congress Listen?

In his book, Polyarchy, Robert Dahl wrote that "a key characteristic of a democracy is

the continuing responsiveness of the government to the preferences of its citizens, considered as political equals" (1).

There are three main categories of scholarship (as outlined

by Miller and Stokes (1963)) that have examined the way in which Congress represents its

constituents: the Instructed-delegate model, the Burkean model, and the Responsible party

model.

According to the Instructed-delegate model, representatives act in accordance with the preferences of their constituents. As such, representation is a form of "delegated" authority. The

way in which this particular model of responsiveness is measured is by observing the correspondence between congressional behavior and constituent opinion. One approach looks

to see how policy conforms with the corresponding changes in popular opinion. Page and

Shapiro find that changes in public preferences of a large enough magnitude correspond with

policy outcomes (1983).

Additionally, several scholars have found evidence that when the

public opinion has turned in favor of change, policy will match in the following years, particularly for issues the public finds important (Monroe 1979; Erikson, MacKuen, Stimson 2002).

Other scholars examine the link between constituent opinion and the behavior of elected

representatives or candidates across districts and between senators of the same state, finding positive relationships between constituents' opinions and their representatives' voting

behavior (Ansolabehere, Snyder, and Stewart 2001; Stimson, MacKuen, and Erikson 1995).

In line with this approach, Miller and Stokes examined the correlations between measures

9

of candidate and voter opinion on the issues of civil rights, social welfare, and foreign policy

and found that the opinions of those elected into office correlated most strongly with district

opinion, particularly in the area of civil rights (1963). They sampled 116 House districts in

the 1958 elections, however the samples varied, with sometimes less than 5 individuals in a

district. This lack of data results in inefficient estimates of voters' preferences at substate

levels. Achen argued that Miller and Stokes' correlation coefficients were not an adequate

measure of representation since large correlations can be observed when opinions are far

apart and small correlations can be observed when they are close together (1978). Contrary

to Miller and Stokes, Achen found that those who were not elected were better representatives of voters than winners and Achen did not observe significant variation across issue

areas. However, using a different methodology, Achen also found that there was a strong

positive association between district and member opinion.

Finding representative measures of opinion has been a persistent problem in this literature. Brace and his collaborators also examined state level opinion using representative

samples from a survey, however those estimates were also highly variable when examined

at the level of specific issues (2002). Another study by Clinton combined surveys to increase the sample size, resulting in over 100,000 combined responses, however there were

still fewer responses for specific issue areas (2006). Taking the mean or median of a small

sample of responses does not help with the issue of high variance. Clinton's study found

that House representatives were not completely responsive to district mean voter and did

not find strong evidence supporting party voting behavior in the House either, casting some

doubt on the Instructed-delegate model and party-based models of Congress. Recent studies

using multilevel regression and poststratification (MRP) to model constituent opinion at the

state or district level have found a solution to the problem of sample size (Lax and Phillips

2009; Park, Gelman and Bafumi 2004; Warshaw and Rodden 2012). Bayesian statistics and

multilevel modeling better leverage information about the respondents' demographics and

geography to provide estimates of opinion. While many studies found evidence to support

10

the Instructed-delegate model of representation, measures for constituents' opinion might be

improved with new methods like MRP, particularly when examining subpopulations.

In the Burkean model, representatives act in accordance with the interests of their constituents, instead of constituents' preferences. Voters thus entrust their representatives with

the responsibility of crafting policies that would best serve their interests. This model would

fit with Mayhew's description of representatives' behavior as advertising and credit-claiming

(1974). He argued that there was very little position-taking, though this was not as much

the case with senators, as representatives would focus on distributing particularistic benefits

to their home districts. Since reelection was the proximate goal, representatives would seek

to please their constituents to retain or capture their votes for the next cycle. Now whether

constituents would be most pleased with representatives who acted on behalf of their interests or preferences may be open for debate, regardless of the specific genre of scholarship,

Mayhew's argument unquestionably places the legislator in a position where he must be in

some way responsive to his constituents.

Fenno is arguably another scholar of the Burkean tradition (1977). While what representatives do in the capital is important, what really matters (from the electoral perspective) is

how they spend their time in the district, since this is how they cultivate trust. A representative's homestyle, or the tool by which constituent trust is cultivated, is his allocation

of resources, presentation of self, and his explanation for activity in Washington. It is not

the policy that is relevant, since constituents care more about the representative's homestyle.

However, policy does have some relevancy, even in the Burkean model, insofar as a representative's behavior in Washington cannot be used to subvert constituent trust. Challengers can

set the agenda in political campaigns to highlight inconsistencies in the incumbent's voting

record. Fenno argues that members are probably only constrained by one or two issues, but

on the majority of votes they can do as they wish as long as they are able answer for it

11

later. For example, Powell's amendment on HR7535, which called to block appropriations

of taxpayer money to construct segregated schools, created a strategic voting scenario. The

Democrats supported federal aid to schools and the Republicans did not. However, Southern

Democrats who were otherwise in favor of the aid, did not like the amendment for racial

integration. Some Republicans voted for the amendment since then they could be sure that

the bill would not pass. Likewise, some Northern Democrats votes against the amendment,

knowing that their Southern counterparts would vote against the bill if the amendment were

added. Ultimately, this was a killer amendment, which Republicans knew would have the bill

rejected. However, the Republicans who voted for the Powell amendment and the Northern

Democrats who voted against it would still have to face their constituents, and likely with

the vote pulled out of the context of the strategic voting environment. Trust was crucial

in order for this voting scenario to occur and some members just could not take that risk.

Representation and support are inseparable as members don't want to alienate their constituency. According to Fenno, the challenger controls which decisions a representative will

need to explain to his constituency. However, with information more accessible than ever

before, challengers may no longer be the powerful agenda-setters they once were. Though in

a more recent study, Ansolabehere, Snyder, and Stewart also argued that the more vulnerable the incumbent, the more attentive to the mainstream of the electorate he will be (2001).

In the Responsible party model, constituents express their policy preferences by casting

their votes for a particular party's platform where members serve as agents of the national

party. Miller and Stokes critique this model as not having a well-thought out concept of

representation (1963). The voters either affirm or reject the party platform and are viewed

as part of a national constituency instead of a local one. Scholars such as Schattschneider

(1975) and former President Wilson did not find a system of district-based forces in the form

of preferences or interests normatively good for government since it prevented members from

coordinating on national level policy. This is primarily due to the fact that the local politics

median voter is not the same as the national median voter.

12

In empirical support of the

Responsible party model, Ansolabehere, Snyder, and Stewart show how House candidates

do not converge to the district median, though more liberal (conservative) candidates run in

more liberal (conservative) districts, so there is responsiveness in this way (2001). However,

another study found that voters appear to punish candidates who vote too often at either

ideological extreme, using ADA scores (Canes-Wrone, Brady, and Cogan 2002).1

In all three of these models of representation the vote is the primary mechanism by which

members are tied to their constituents, be they preferences or interests. Stimson argued how

citizens may act in a reactionary or thermostatic way when voting for elected officials in an

attempt to keep them in line with their interests (2004). Public opinion is always moving

but the pace of it may vary, with opinion changing rapidly in times of crisis or in judging

an incumbent's performance in the months prior to an election. This agrees with Fiorina's

argument that retrospective evaluations of performance drive vote choice (1981). However,

politicians may rationally anticipate opinions prior to their elections (Stimson, MacKuen,

and Erikson 1995).

Politicians reconcile their own ideal point for policy with that of the

median voter in their home district, understanding that they cannot drift too far away from

the median in their behavior. "Hardly indifferent, these politicians are keen to pick up the

faintest signals in their political environment. Like antelope in an open field, they cock their

ears and focus their full attention on the slightest sign of danger" (Stimson, MacKuen, and

Erikson 1995, 559).

Representatives must be mindful of the opinions of the people who

allow them to keep their jobs. With the electoral goal being the necessary antecedent to all

other goals, representatives rationally respond to the preferences or interests of their constituencies. Of course elected officials may feel a degree of social pressure to respond to their

constituents in addition to the electoral incentive (Glynn et al. 1999, 303).

Voters also tend to elect people like themselves, so representation may be symbolic or descrip'This study used the presidential vote as a catch-all proxy for district public opinion. Presidential vote

share, while commonly used, is not an ideal measure since it not possible to disaggregate public opinion into

individual issues to examine the relationship between district level preferences and the voting behavior of

their representatives.

13

tive (Glynn et al. 1999). This may also be reinforced by the representative's presentation

of self. As an example of a person-to-person homestyle Fenno includes the following quote,

"if a man takes a bite of your chewing tobacco - or better still if he gives you a bite of his

chewing tobacco - he'll not only vote for you, he'll fight for you" (1977, 900). By sharing

a bite of chewing tobacco, the representative is presenting himself as an equal. This is an

activity one might do with a neighbor or friend, which probably made this constituent more

likely to trust that this candidate would represent his interests. This type of homestyle is

more common in homogeneous districts where it is easiest to relate to a common culture

or demographic. However, symbolic representation may be more than just a way to garner

trust, as it may also shape the way policy is made. A representative who descriptively looks

like his constituents may be more likely to act in their interests.

How Might Differential Responsiveness Persist in a Democracy?

The demographic makeup of Congress is not descriptively representative of the American

public. Some studies assert that the demographic makeup of the legislature matters both

in terms of representing the needs and preferences of constituents.2

In a randomized field

experiment in India by Chattopadhyay and Duflo, areas that had more women Village Council members in head positions were found to have different types of public goods provided

(2004). They found that female leaders invest more in infrastructure that is directly relevant

to the needs of the women in the village. Additionally, a ruling class that does not look like

the people it represents may send messages to voters about efficacy, such as who belongs in

the political process (see working paper by Posner and Kramon on how having a coethnic

political leader positively affects primary school attendance in Kenya).

This may suggest that individual senators vote according to their personal preferences. A

2

Much of the research on descriptive representation is in the field of comparative politics. A small sample

of the vast literature includes: Posner 2005 examining ethnic politics in Zambia; Matland 1993 studying

female representation in Norway; and Chattopadhyay and Duflo 2004 examining female representation in

India.

14

U.S. study found that legislators with more daughters had more feminist voting records

(Washington 2006). Similarly, those who come from more privileged economic backgrounds

are more likely to shape policy in favor of the wealthy. Carnes found evidence that previous professional histories are related to a member's voting record (2011). He found that

representatives with different occupational backgrounds, coming from similar districts, vote

differently. A congress with members from poorer backgrounds would therefore be expected

to adopt politics more in line with the interests of the lower and middle-income groups. 3

However, the upper class bias of Congress does not vary over time, while policy responsiveness does (see Gilens 2011). This suggests that the responsiveness gap cannot be entirely

explained by personal preferences.

Some scholars have suggested that an association between high-income voters' opinion and

senators' votes might be due to the fact that the public adopts the views of its policy-makers.

Since high-income constituents are more likely to read the newspaper or watch the news,

they receive these elite cues, aligning their opinions with elite behavior. Page and Shapiro

believe that collective deliberation relies on such cue-taking from the press and public figures

(1992). Zaller agrees, arguing that individuals rely on elite leadership cues for topics beyond

their understanding (1992, 14). Stimson argues that a small minority of interested members

of the public may be the opinion leaders for the rest of the population (2004).

However, Druckman and Nelson provide evidence against elite cue-taking with their study

that found that conversation can mitigate such influence (2003). When members of a group

received a news story with different framing and then engaged in conversation, the framing

effects went away. This may be taken as evidence against this alternative causal story. As

long as alternative frames are accessible, elite influence is muted and the public is freer to

develop different opinions.

Political resource theory asserts that higher-income individuals are more politically engaged

3 Carnes found no association between members' voting records and their outside income or wealth (2011).

15

since they have the greater resources of time, money, and education. The rich have a greater

ability to make campaign donations, which can buy them influence (Brady, Verba, and

Scholozman 1995). This is particularly true of those at the the very top end of the U.S.

income bracket. A survey of the top one percent in Chicago found that two-thirds of respondents reported contributing money to politics compared to just fourteen percent of the

general population (Page, Bartels, and Seawright 2013).

Given this differential political

engagement of those at the very top, examining their opinions at the national level would

be especially important in the study of this question. When this participation is stratified

along socio-economic lines, "participatory distortion" exists whereby those who participate

(wealthy constituents) send biased signals to policy makers and these signals in turn result

in biased policy outcomes (Verba, Schlozman, Brady 1995, 468), presenting a problem for

democracy.

Hall and Wayman (1990) found that members of Congress are more responsive to organized

business interests than the unorganized masses, even when voters have strong preferences

and the issue is considered important. Organized political action groups use targeted contributions to the members and chairs of particular congressional committees who are in

the best positions to promote their interests (Romer and Snyder 1994). These groups will

specifically add or drop members who change their committee assignments to areas that are

no longer relevant to the interest group. Larger organized interest groups, like a regional

steel producer, may be able to offer politicians larger financial contributions, but if they

can also guarantee more strength of direct voter support (from their employees), then their

contributions are scaled down (Bombardini and Trebbi, Working). This may be marshaled

as further evidence that the wealthy and monied interests have the capability to disproportionately influence national policy. While collective action by large groups is difficult to

achieve even when there are shared interests, small groups are better able to organize and

press the government for policies that support their interests, sometimes at the cost to the

majority (Olson 1965). Small groups are able to organize because they are brought together

16

by selective incentives or particularlized benefits. In a large group, because all share in the

spoils there is an increased incentive to free ride and not participate, which could leave the

interests of the middle class and poor may be largely ignored.

Mayhew argues that since there are high information costs for constituents to faithfully

keep track of their representative's voting record, there may be occasions such as those described by Hall and Wayman (1990) where members act against constituent interests when

it may further reelection prospects in another way.

One such way would be responding

to monied interests who promise to support future campaigns.

Mayhew's representatives

are vote-maximizing agents, not those who seek programmatic impacts. Fenno discusses a

member's constituency as nests of concentric circles, where the innermost circle, his personal

contacts, are his strongest supporters (1977). This is then followed by the primary, reelection and geographic outer circles. The representative's first responsibility is satisfying the

demands of his inner-most circles since without them he cannot be reelected. These inner

circles are disproportionately occupied by the wealthy and other monied interests.

The arguments concerning descriptive representation, elite cue-taking, and differential allocation of political resources and ability to organize can all at least partially explain why

certain segments of the population, such as the wealthy, may be able to exert more influence

over policy-makers.

More research must be performed in order to be able to conclusively

adjudicate between these competing explanations. The task of this paper, however, will be

to examine the nature of the relationship between public opinion and policy making, not to

test the causal mechanism.

Differential Responsiveness By Income

As already discussed, there are many scholars who have examined questions exploring the

relationship between public preferences and government policy-making. However, there are

17

only a few authors who have directly examined the question of differential responsiveness of

legislators to their constituents by income group. In his book, Unequal Democracy, Bartels

examines this question using Poole/Rosenthal NOMINATE scores and several key roll-call

votes of senators (2008).

He finds that senators were consistently more responsive to the

opinions of high-income constituents, however these conclusions might have been driven by

the fact that he selected votes that would generate results conforming with his argument.

Using the same data, I successfully replicated the part of Bartels' study that was examining

specific roll call votes, but in more recent roll call votes (from 1999-2004) I found his key

statistically significant finding regarding responsiveness to the high income on the issue of

minimum wage may have been outlier.' Though much like Bartels found, for the issues of

minimum wage and abortion, very few of the estimated effects were statistically distinguishable from zero. In Figures 61 to 66 in the Appendix I show, using the same estimation

technique, how the probit estimates on the votes from my study compare to Bartels' probit estimates on minimum wage and abortion.'. My survey data, though large, were not

representative at the state level and instead of a general measure for ideology I used the

issue-specific ideological measure.6

Erikson and Bhatti replicate the part of Bartels' study using NOMINATE scores, but they

were not able to reproduce his findings using two more recent datasets (forthcoming). They

believe this was likely due to insufficient variation in opinion across income groups for the

more recent time period of their study. While it may be possible that senators are only

responding to their high-income constituents' preferences, if these preferences look like the

preferences of the lower-income constituents then there is no way to measure this differential

effect. It is also possible that Erikson and Bhatti's measure of policy preference does not

adequately capture the variation across income groups. A more direct ideological measure,

4

None of the point estimates for high income opinion on the thirty-four recent votes fall within the

confidence interval for the minimum wage vote Bartels selected.

5 Bartels' estimate for minimum wage was based on votes for the Minimum Wage Restoration Act of 1989

(HR2) and his estimate for abortion on the Harken motion to table the Armstrong amendment (HR5257)

6

Though this was rescaled to conform with Bartels' ideology measure on a -1 to 1 scale of liberal to

conservative.

18

relating to specific policy areas, would have perhaps produced different results.

Bruner Ross, and Washington (2011) matched legislative and constituent votes on ballot

initiatives in California and also did not find that the rich are better represented than the

poor. In their study as well, the views of the rich and poor were highly correlated, and as

such, both groups were found to be well-represented.

Tausanovitch found that the expressed preferences of the wealthy are better represented

in both the Senate and House than the poor using a continuous measure of political preferences based on responses to policy questions (working). He believes this is the reason Erikson

and Bhatti are not able to find results in their study using just a 5-point ideology measure.

The continuous measure of preferences provides more information about individuals in policy

space. The dependent variable consists of all roll calls taken in both chambers from the 108111 Congresses. However Tausanovitch has not explored the effect of income group opinion

across issues. He also rather arbitrarily picked his income categories, classifying those with

household incomes less than $25,000 as poor and respondents with household incomes over

$100,000 as rich.

Gilens has attempted to answer a similar question by looking at how responsive the government as a whole is to the populace by income, instead of just examining the responsiveness of

senators, like Bartels (2012; 2008). Gilens looks at how this differential responsiveness varies

across the policy areas of foreign policy & national security, social welfare, economic policy,

and religious issues, running twelve separate logit regressions. His dependent variable is the

policy outcome, coded with a 1 if the proposed policy change took place within four years of

the survey and 0 if it did not. He also uses opinion measures relating to specific issues, rather

than using a general ideological measure, like Bartels. Gilens found that the responsiveness

gap between the wealthy and the poor was negligible on issues of social welfare and largest

for foreign policy.

19

While roll-call votes neglect to account for the power of agenda-setting in determining which

issues are considered and which are ignored, I argue that it is first necessary to examine the

responsiveness of one body of government at a time before looking at interactions between

bodies necessary to enact policies. Perhaps the failure of representation does not stem from

any one branch, but is distributed amongst all of them. Alternatively, it may be that one

body of government is responsible for the bias that Gilens finds in policy outcomes. It may

also be by the collaborative efforts between the bodies of government where representation

fails. It is important to analyze each separately so that this differential responsiveness may

be clearly attributed to its source.

Informed by the choices of Bartels, Tausanovitch, and Gilens, I examine the differential

responsiveness of senators to low, middle, and high-income opinions across the issue areas of

economic policy, social policy & civil rights, foreign affairs, and healthcare. I also adopt the

perspective of the Instructed-delegate model of representation and expect to find evidence

of a positive relationship between constituents' opinions and the voting behavior of their

representatives.

Overview of Project

I begin by using a large and more diverse set of data sources and surveys to allow me to

examine public opinion at the issue-specific level. Since these surveys are not representative

samples of each state, as the ANES survey data used by Bartels, I perform multilevel regression and poststratification (MRP) analysis. This approach allows me to more accurately

represent public opinion at the state level and for specific income groups by combining survey and census data (see Warshaw and Rodden 2012). Previous work has not been able to

answer this specific question due to insufficient sample sizes in national surveys. I am able

to connect the vote of a senator to his or her constituents' opinions across a broad range of

issues. I then examine these opinions at the fine-grained level of income within each state.

20

Once I have these estimates of income group opinion by state and issue area, I use them

as the independent variables of interest in the second stage.7

For the second stage I first

estimate the ideal point (on the liberal to conservative scale) for each senator and for each

issue area. I then take these estimates and use them as the dependent variable in a standard

OLS regression with the MRP estimates of opinion and a dummy variable for whether or

not the senator is in the Republican Party.8

A discussion of the results and substantive

implications follows.

Data

I use IPUMS for the necessary census data (5% sample of population from the year 2000)

like income, race and percent urban for each state. I then combine 3 large-N surveys to

measure pubic opinion across a variety of issues: the 2000 and 2004 National Annenberg

Election Survey and the 2006 Cooperative Congressional Election Survey (CCES). I chose

twelve issues where I could find similar question wording across at least two different surveys. This yielded an average of 56,707 responses per issue area. The issues are minimum

wage, social security, estate tax, abortion, gun control, gay marriage, school vouchers, environment, trade, war in Iraq, immigration, and health insurance. Responses are coded as

1 if the position is supported, and 0 otherwise.9

I performed factor analysis to make sure

that these questions across different surveys were statistically similar, such that variations

across each of these surveys mainly reflect variations in fewer unobserved variables, namely

public opinion. Across most issue areas, the proportion of the variance explained by the first

7

Unfortunately, I am not able to propagate the uncertainty of these Stage 1 estimates into the second

stage. However, much of the current MRP literature does not do so either.

8I also use another second stage estimation technique, a generalized estimating equation model for correlated data. In this model the dependent variable consists of all roll call votes in a given issue area, which are

regressed on the same independent variables used in the ideal point regression. I then compare my results

from each of these estimation strategies and discuss their substantive implications. The results from this

method and interpretation are available in the Appendix

9

Following Lax and Phillips (2009) I coded "don't know" as 0. Arguably, one might assert that it indicates

a deference to the status quo. Missing responses were dropped.

21

component was greater than 0.7, with the exception of gay marriage and Social Security.1 0

As the respondents were not the same across surveys I compared respondents by income

group, sex and race. The results suggest not only that public opinion was stable across the

time period of these three surveys, but also the questions across surveys are comparable

enough to be combined. I also performed factor analysis by each respondent for questions

across different issue areas for each of the three surveys. I found that the issue areas were

sufficiently distinct to warrant their individual treatment. Comparing each issue area against

each other, I found the proportion of the variance explained by the first component was less

than 0.7."

The surveys identify the home state of each respondent so they can be used in MRP analysis."

Each respondent also has associated demographic information such as gender, race,

education, and income. I examine three sessions of the Senate (106-108), which corresponds

to the time frame, 1999-2004. In the 2000 election the Senate went from a Republic majority

to being evenly split between Republicans and Democrats. The Senate then went back to

being a Republican majority for the 108th Congress.

For the issue area and ideological direction of the senators' roll-call votes, I use data from

the Policy Agendas Project. This organization uses NOMINATE to score the ideological direction of a given vote, which has been a generally accepted metric in the American political

science literature."

Using this dataset and the roll call datasets from the Senate website, I

coded the Senate responsiveness dependent variable. I coded the votes such that a 1 corresponded to the conservative position on an issue and a 0 corresponded to the liberal position.

I recoded the survey responses to questions asked in the liberal direction on minimum wage,

gun control, environment, and health insurance, so that all of the responses were coded in

10

Data available upon request.

"Data available upon request.

12

Only the CCES data contains respondents from Alaska and Hawaii.

3

1 Poole and Rosenthal apply a spatial voting model to congressional roll-call data to estimate ideology in

Congress. Legislators ideal points are then estimated within choice spaces on various dimensions.

22

the conservative direction to match the votes. Votes which could not be classified as liberal

or conservative based on their NOMINATE score, which mostly included unanimous votes,

were not used in the estimation.

The reported top household income category for all three surveys was "more than $150,000".

This category, alone, was made the high income category. The low income category includes

all respondents with household incomes below $25,000 and the middle income category captures those earning $25,000 - $150,000.

While household income is not an ideal measure,

as I am unable to adjust for the number of people in the household, these thresholds are

sufficiently extreme that a poor household is unlikely to be misclassified as a rich household

and a rich household for a poor one. To my knowledge, this is the first study measuring

income group public opinion where the high income threshold is set as high as $150,000, representing the top 10 percent of the US household income distribution. This is likely because

previous studies were not able to correct for the scarcity of data for individuals at the top.

MRP is uniquely suited for estimation where limited data is available. I also run the same

set of analysis with the more equal income breaks (equal in terms of survey categories) of

keeping low income as less than $25,000, but setting middle income as $25,000 to $50,000,

and high income as above $50,000 (above the median for the time period). These are the

same income breaks that Bartels uses in his study. Although both Bartels and Bhatti find

their results are unchanged when using different income thresholds, they have not tried this

drastic a change. A recent survey of top earners in Chicago found they are more socially

liberal and economically conservative than others (Page, Bartels, and Seawright 2013). This

suggests that a national study examining the preferences of the top tenth would be an important contribution to the field. In order to test how responsive senators are more generally

to their constituents, I also run the analysis without any income breaks, with state opinion

estimated by issue area.

23

Method: MRP and Poststratification

MRP models each response as a function of its respective demographic and geographic characteristics. It assumes that effects within a group of variables are related to each other

by their hierarchical structure. MRP applies Tobler's Law such that individual observations that are close together in space or on certain dimensions are assumed to have more in

common. The multilevel model pools group-level variables toward their mean, with greater

pooling when the variance is small and more smoothing when there are fewer respondents in

the group. MRP produces more accurate and robust estimates than other forms of estimation like disaggregation, particularly in estimating opinion in small states and for the very

wealthy, which have fewer respondents (Warshaw and Rodden 2012).

In the model below I estimate each respondent's preferences as a function of his or her demographic characteristics and state (the senator's constituency). Individual i indexes a, r-g, s

for age (younger than 27, 28-37, 38-57, 58-77, 78+) race & gender (white male, black male,

hispanic male, other race male, white female, black female, hispanic female, other race female), and state, respectively.

-i,,:,,b

represents the fixed effects for the interaction between

each income group and the percent living in an urban area. The model allows individual

attributes to predict state and income level ideology. It also manages to correct for some of

the shortcomings of the survey sample. Surveys tend to oversample older respondents and

this might particularly be true for those in the top income group. This model is able to

compensate by re-weighting opinion estimates to better reflect the actual population such

that the under-sampled populations, like young high income respondents (captured by age

and income covariates), receive a greater weight. Additionally, the model incorporates both

within and between state geographic variation.

24

Hierarchical model for individual respondent:

Pr(yi

=

ageU ~

Cla"

+ yincurb + arace-,ender

1) =og-O

(,

agA)a

ar-gender ~a(0,

astate)

age

= 1, ...

)5

,

,cegender)

rg

8

1,

Following previous work with MRP, I assume that the effect of demographic factors does not

vary geographically (see Warshaw and Rodden 2012). In the state level of the model, each

state is allowed to vary with its own intercept. The state effects are modeled as a function of

its region of the country, the state's average income, and the percent of the state's residents

living in urban areas.

~

V7low-inc

(state

- income,

+

ymid -

income, + -yhi-inc - income.,

2

)

The next step is poststratification where the estimates for each respondent demographic

geographic type (7rt) is weighted by the percentages of each type in the actual state populations (Nt).

~mrp

states

tEst

=

Twt

(EtEsNt

There are 51 states (including D.C.) with 120 potential demographic types in each, which

yields 6,120 possible combinations of demographic and state values but not all of these combinations were observed in the data.

For each state and income group combination, the average opinion over each type is calculated. These estimates become the independent variables of interest for the second stage

of the estimation.

25

Figure 1

Minimum Wage

UT

NH

WY

AZ

MT

AK

OH

GA

U

0

A

0

*A

0

*A

0

A

**A

**A

U

*A

U

*

A

*

0 A

U

q

A

0

*A

U

0 A

N

*

A

U

* A

N

*

A

*

*A

E

4

0*A

gA

0

U

0

A

*A

0

0*A

*

0

A

**A

N

* A

U

*A

0

* A

*

* A

N

0 A

u

*A

0

0 A

0

*A

*A

0

U

*

A

*

9

A

*A

0

S S

U

a

m

*A

U

*

A

N

0 A

ID

HI

WI

RI

Co

OK

TX

Sc

ME

KS

NE

FL

MN

MO

OR

LA

SD

TN

(n ND

IN

WA

KY

MI

IA

PA

NV

CA

NC

VT

WV

AL

NM

CT

MS

DE

AR

NJ

MD

VA

IL

MA

NY

DC

(56,260,16)

(19,154,14)

(17,63,2)

(121,667,58)

(41,106,6)

(9,89,8)

(243,1147,48)

(144,902,79)

(46,174,7)

(14,62,3)

(160,660,32)

(18,98,0)

(85,483,38)

(80,301,18)

(334,2033,183)

(75,322,19)

(44,164,4)

(89,331,8)

(44,129,5)

(309,1685,125)

(109,528,53)

(138,598,30)

(118,508,30)

(70,288,19)

(30,92,3)

(120,496,27)

(20,68,1)

(137,595,19)

(150,823,57)

(102,339,10)

(234,1134,67)

(78,341,14)

(229,1161,67)

(42,283,22)

(396,2601,367)

(160,719,46)

(17,53,4)

(78,196,6)

(92,344,20)

(47,227,17)

(39,266,42)

(49,135,7)

(16,82,6)

(104,239,9)

(64,651,80)

(52,541,74)

(82,691,102)

(165,1125,118)

(63,429,56)

(242,1347,146)

(1,3,1)

oA

S

S

*

A

0

N

*

a

a

m

S

w

0.0

0

A

0

A

q A

*

A

0 A

* A

*

A

0.2

0.4

0.6

MRP Estimated Opinion

26

0.8

1.0

Figure 2

Minimum Wage

(Equal Breaks)

U

U

UT

NH

WY

ID

AZ

ME

MT

OH

AK

OK

SD

MO

U

A

A

A

A

0

0

U

us

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

*

U

0

0

U

U

me

OR

*

TN

KS

FL

ND

WI

MN

HI

RI

NE

U

U

*

*A

*

*

U

U

0

*

*

U

N

0

S

*

*

*

*

*

SC

*

IN

CO

U

*S

(D

*

o

*

C

C

SVT

5

& WV

TX

LA

IA

GA

KY

AL

MS

MI

CA

NM

NV

PA

VA

WA

NC

CT

AR

DE

NJ

IL

MA

NY

MD

DC

U

U

*

*

*

*

*

U

U

a

U

U

A

A

A

A

A

A

C

C

*

* A

*

*

U

0

a

*

*

*

U

0.0

A

A

*

*

U

U

U

0

S

0

U

U

N

CA

*

*

*

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

CA

*

U

(56,186,90)

(19,84,84)

(17,46,19)

(46,132,49)

(121,384,341)

(44,110,58)

(41,79,33)

(243,757,438)

(9,49,48)

(80,219,100)

(30,66,29)

(138,404,224)

(118,325,213)

(120,344,179)

(89,238,101)

(309,1049,761)

(20,48,21)

(160,434,258)

(109,315,266)

(14,32,33)

(18,59,39)

(44,97,37)

(75,207,134)

(137,400,214)

(85,257,264)

(17,38,19)

(78,142,60)

(334,1170,1046)

(70,191,116)

(78,247,108)

(144,517,464)

(102,217,132)

(92,238,126)

(49,89,53)

(234,707,494)

(396,1370,1598)

(47,121,123)

(42,167,138)

(229,734,494)

(82,373,420)

(150,469,411)

(160,451,314)

(39,138,170)

(104,184,64)

(16,52,36)

(64,317,414)

(165,641,602)

(63,219,266)

(242,782,711)

(52,256,359)

(1,2,2)

*A

0

*

*

*

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

0.2

0.6

0.4

MRP Estimated Opinion

27

0.8

1.0

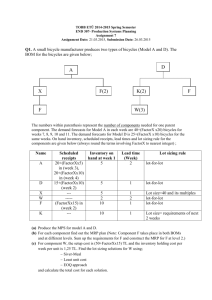

Figure 1 and Figure 2 show the estimated opinions for increasing the minimum wage

of income groups by state.14 Figure 1 defines income as the top ten percent, and Figure 2

has more equal income breaks as discussed in the previous section. The square represents

the poor, the circle represents the middle-income, and the triangle represents the wealthy

respondents. The numbers on the right are the sample sizes for the poor, middle income,

and rich respectively in each state. A one on the X axis corresponds with the conservative

opinion that the minimum wage should not be increased, while a zero denotes an approval for

the increase. The figures of the MRP estimates for the other eleven issue areas are provided

in the Appendix as Figures 2-24.

Interestingly, the top ten percent are more liberal than when high income is defined as

above $50,000. However, they are still less likely to support the increase in minimum wage

than the middle or low income respondents. Low income respondents are most likely to

support the increase than any other group.

The top 10 percent are also more liberal on the issue of abortion than the other high income

group. The high income group is overall more likely to be against placing restrictions on

abortion while the low income group holds the most conservative position. This may be because lower income individuals are typically more religious or traditional than upper income

groups.

The high income are less likely than the poor or middle class to agree that the government should do more to protect the environment. The poor are most liberal on this issue.

This is likely because the high income fear government encroachment on their business interests.

Self-interestedly, the high income favor eliminating the estate tax and this is much more

14

Included in the Appendix is this same figure but for MRP estimates of pooled constituent opinion (no

income group breaks).

28

apparent for the top ten percent. The low income are most likely to oppose the elimination

of the estate tax.

There does not appear to be a clear income group level opinion for the issue of gun control,

regardless of income breaks.

This may be more determined by where in the country the

respondent lives.

Both the high and low income respondents are more liberal on the issue of gay marriage

than the middle income. The reason for this is less clear.

High income respondents are less likely to support a federal health insurance plan than

the middle and low income groups. Low income respondents are most in support of the program. The top ten percent appear more conservative on this issue than the more inclusive

high income group.

The high income are much less likely to want to restrict immigration than the low and

middle income groups. The top ten percent are much more liberal on this issue than the

more inclusive high income group. This accords with the Hainmueller and Hiscox's finding

that the highly educated are more likely to support immigration than those with less education (2010), as income and education are highly correlated.

The low income respondents are much less likely to believe the situation in Iraq was worth

going to war over. This may be because they more acutely felt the costs, since low income

youths are much more likely to enlist. Interestingly, the top ten percent are more liberal on

this issue than the more inclusive high income group.

The low income respondents are least likely to support privatizing Social Security, while

the high income are most in favor of its privatization. Again, we see the top ten percent is

29

more liberal on this issue than the more inclusive high income group.

A clear distinction across the income groups does not arise on the question of whether

school vouchers should be an option. However, the top ten percent are slightly more likely

to prefer the privatization than the other two groups. This same pattern does not appear

for the income groups with equal breaks.

The top ten percent are much more likely to be pro-free trade, while the low income respondents are most against free trade. The more inclusive high income group is also more

in favor of free trade than the other groups but the disparity is less substantial.

There are apparent differences in opinion across income groups for many of these issue

areas. Interestingly, the top ten percent are more liberal on issues like minimum wage, abortion, gay marriage, Social Security, and the Iraq War than the more inclusive high income

group. They are also more conservative than the inclusive group on issues like the estate

tax, school vouchers, and free trade." I found that these differences between income group

opinions were statistically significant. The difference in means between the top ten percent

and the more inclusively defined high income group opinions were statistically distinct as

well. Tables presenting results from the t-tests are provided in the Appendix.

As a validation test of the MRP estimates, I checked to see how correlated they were with

Tausanovich and Warshaw's state level ideology measure from their 2013 paper, "Measuring

Constituent Policy Preferences in Congress, State Legislatures, and Cities". Their estimates

were produced using Item Response Theory and were found to outperform previous measures

of citizens' policy preferences.

In their paper, Tausanovitch and Warshaw create a measure for ideology at a state level,

1 5Though "free trade" would technically be "liberal" in the classical economic sense of the term, here by

"conservative" I am referring to an alignment with the Republican Party.

30

aggregated across all issue areas and income groups. In contrast, in this paper I develop

my estimates by issue area and a number of different aggregations of income level. Figure 3

shows one example of how my state-level opinion MRP estimates by issue area are positively

correlated with Tausanovitch and Warshaw's general estimate of state opinion when looking

at all income levels in aggregate. The validation plots for the other eleven issue areas are

contained in the Appendix as Figures 14 to 24 with correlations included in the legend of

each plot.

Figure 3

Minimum Wage

(No Income Breaks)

U

U

-r

Co

* All Incomes (Cor. 0.558)

0.12

0.14

0.16

0.18

0.20

0.22

0.24

0.26

State-level Opinion, MRP Estimates

For ten of the twelve issue areas, the relationship between the two measures are positively

correlated.16 The remaining two issue areas, school voucher and free trade, despite having a

negative correlation, show little variation in the opinions across states for these issues (10%

of the scale, as opposed to ranges more typically around 30 to 40%); as such correlations are

not a meaningful measure of performance. This overall pattern of positive correlation is to be

expected despite the fact that Tausanovitch and Warshaw's measure was not issue-specific,

16In particular, middle-income group opinion was consistently found to be the most highly correlated

income group opinion with their measure largely because this group constitutes majority of the population.

31

as both measures are obtained using survey responses from the same time period and all

three surveys used in this paper were also used in Tausanovitch and Warshaw's study (in

addition to six others).

Figure 4

Minimum Wage

Minimum Wage

(Equal Breaks)

Ln

0

o

*

Ci

.Q

A

AA

AA AL

.2

AL

AL~

A

o

- /

A

*A

A

A Lw

LnAe

Cr

o1

0

LA

A

1P

S

*1

A

Low Income (Cor 0.200)

" Midde income (Cor. 0.708)

A High icome (Cor. 0.121)

A

o

II

0.05

0.10

0.15

I

1

0.20

0.25

0.30

*Low Inome (C r .0.189)

* Middle kcome (Cor. 0.45)

A High Income (Cor. 0.559)

0.35

0.10

0.05

0.15

Minimum Wage

(No Income Breaks)

0

0

(a

0)

U)

P

0

0

*

U

U

0

0

0

w

All

_

0.12

0.20

0.25

State-level Opinion, MRP Estimates

State-level Opinion, MRP Estimates

0. 14

0.16

State-level

0.20

0.22

Opinion, MIRP

Estimates

0.18

32

Incomes (Cor. 0. 715)

0.24

0.26

0.30

0.35

I further examined the correlation between my MRP estimates and state weighted averages of the raw survey data in order to better validate in an issue specific manner, especially

for school voucher and free trade in which the low variation across states made it difficult

to compare to Tausanvitch and Warshaw's more general measure. Figure 4 presents this

relationship for the issue area of minimum wage. The raw data validation plots for the other

eleven issue areas are available in the Appendix as Figures 26 to 36. The simpler disaggregated measures were often used in the literature to date examining legislative responsiveness

to public opinion (Brace et al. 2002; Clinton 2006; Miller and Stokes 1963), however given

the paucity of the number of respondents, estimates of opinion for subpopulations have a

large amount of uncertainty (Achen 1978; Lax and Phillips 2009; Warshaw and Rodden

2012). However, the MRP estimates should still be positively correlated with these simpler

measures when the sample size is large, and there is evidence of this linear relationship across

the issue areas.

As expected, MRP estimates of constituent opinion in aggregate by state is highly correlated

with the simpler estimates across issues, indicating a positive linear relationship. Here the

sample sizes are large since the opinion of particular income groups is not being estimated.

This increases the precision of the state weighted averages, making them more similar to the

MRP estimates of state opinion. The ten issue areas found to be positively correlated with

Tausanovitch and Warshaw's measure are also correlated with the raw weighted averages,

with some issues having correlations well above 0.9. As with my MRP estimates, the raw

weighted averages for the remaining two issue areas also demonstrate low levels of variation

in opinions across states. This confirms that the low variation is not unique to MRP estimation. Despite having little variation, the MRP estimated opinion regarding free trade was

well correlated with the raw weighted averages, and the MRP estimated opinion regarding

school vouchers was one of the most highly correlated issue areas with the raw weighted

averages. This is further evidence that the first-stage MRP estimation was successful.

33

Since averages are highly variable in small sample sizes across issue areas and income, it

is best to separately consider the performance of the middle income MRP estimates as this

is the largest subpopulation. 1 7 Compared to the other income groups, middle income opinion estimates are most highly correlated with the simpler weighted averages of opinion, both

when middle income is described as those earning $25-$50,000 as well as when those earning

$50-$150,000 are also included. These state-level middle-income opinion MRP estimates are

as well correlated with the middle-income raw weighted averages as observed at the aggregate state-level. This, again, validates the first-stage estimation.

However, when comparing the MRP estimates for high and low income opinion to the raw

weighted averages the correlations are not as strong. This is largely due to the increased

variability that results from these sample sizes being smaller than the middle income group.

For low-income opinion, the correlation between my MRP estimates and the simple weighted

averages are positive across all issue areas, although in some cases this correlation is very

weak.18 For high-income opinion, the correlations between the MRP estimates and the simple weighted averages were better for some issue areas when high income was defined as only

the top 10%, while for others correlations improved when high income was defined more

broadly, even though it included a more economically diverse set of respondents (increasing

the variation); in all cases though, the correlations were not as strong as they were for middle

income. This is in fact, specifically why I have chosen to use MRP. Previous scholarship (Lax

and Phillips 2009; Warshaw and Rodden 2012) have shown that MRP results in estimates

that are more reliable with smaller errors. This is particularly true when dealing with sample

sizes that are small, like high and low income respondents to a set of national surveys being

divided by state.

In general, weighted averages of income group opinion by state result in highly variable

17

Middle-income respondents also tend have have lower variance in their responses compared to the lowincome group more generally. This is often credited to the higher levels of education associated with the

middle class.

18

The definition of the low income group does not change in the two different aggregations by income level.

34

estimates due to insufficient sample size. As would be expected, middle income opinion,

the income group with the largest share of the population per state, was found to have the

highest correlations with my MRP estimates across the issue areas. The high positive correlations of aggregate state level opinion with the corresponding MRP estimates provides the

strongest support for the validity of the first-stage estimation.

Method: Ideal Point Estimation and Regression

Now that I have constructed the independent variables of interest for state-income group

opinion, I next construct the dependent variable. Using the CVP estimation procedure created by Fowler and Hall (working), I estimate the ideal point for each senator for each issue

area. I coded the senators' vote as liberal or conservative based on their NOMINATE score

and a conservative vote was set equal to one and zero otherwise. This eases the interpretation with a positive coefficient corresponding to the conservative position on the issue by

the respondents. I then regressed legislator fixed effects and bill fixed effects (to control for

the content of each bill, which is important for comparing legislators who did not vote on

the same subset of bills) on the recoded vote variable for each issue area. I used the median

legislator as the omitted category for the legislator fixed effects. This means the coefficient

on a legislator's fixed effect is equal to the probability (relative to the median legislator)

that the legislator votes in the conservative direction on any given bill. The ideal point

can change depending on the senator's voting record in any given issue area. For instance,

Republican Senator from RI, Lincoln Chafee's ideal point for minimum wage places him just

barely in the liberal direction, while his ideal point for abortion places him in the conservative direction.

I chose this method for ideal point estimation because it performs better with a smaller

set of votes than other estimation techniques. Since I am looking within specific issue areas,

pooling the votes for the time period 1999-2004 still only leaves me with a small number

35

of votes. With only 35 votes and over 100 legislators the results are expected to achieve a

0.05 mean absolute deviation (5 percentage points between the "true" ideal point and the

estimated value). DW-NOMINATE would require 100 bills to provide accurate estimates

(Fowler and Hall, working). It was also found to be highly correlated with the first dimension

of DW-NOMINATE.

After estimating the ideal points for each senator for each issue area, I then ran a standard OLS regression of the ideal points on the first-stage MRP estimates for low, middle,

and high income opinion as well as a dummy variable for whether or not the senator was

Republican. I then block-boot-strapped the standard errors, by resampling the senators with

replacement and reconstructing the dataset such that the senators that were included twice

in a sample have all their bills in there twice and the ones the did not get sampled were

left out. I then reran both regressions generating a distribution of new estimates for the

confidence intervals. My results are shown in Table 1 below for all twelve issue areas.

Table 1: CVP Model Regression Table

Intercept

Low Income Opinion

Middle Income Opinion

High Income Opinion

Minimum Wage

0.32*

Abortion Rights

0.56*

Social Security

0.16

Estate Tax

-0.47*

(0.17, 0.51)

(0.37, 0.80)

(-0.55, 0.92)

(-0.94, -0.10)

1.37*

1.67

-0.65

0.34

(0.21, 2.74)

(-0.91, 3.44)

(-1.37, 0.14)

(-1.02, 1.93)

-1.16

-3.41

0.88

0.30

(-3.64, 0.54)

(-5.99, 0.03)

(-1.99, 3.68)

(-2.11, 2.21)

-0.42

1.17

-0.58

0.10

(-1.22, 0.78)

(-0.35, 2.45)

(-2.05, 0.94)

(-0.99, 1.58)

Republican senator

-0.25*

-0.31*

-0.04*

0.12*

Adj R 2

(-0.28, -0.22)

0.61

(-0.36, -0.26)

0.65

(-0.07, -0.01)

0.06

(0.10, 0.14)

0.40

123

118

N

123

Bootstrapped confidence intervals in parentheses

* indicates significance at p < 0.05

122

36

Table 1: CVP Model Regression Table

Intercept

Low Income Opinion

Middle Income Opinion

High Income Opinion

Republican senator

Adj

R2

Gun Control

0.12

Gay M arriage

0.8 7*

(-0.12, 0.30)

(0.72, 1.01)

0.36

1. 39

(-1.09, 1.87)

(-0.65, 2.80)

-2. 75*

-0.54

(-2.94, 2.25)

0.05

(-4.44, -0.21)

-0. 07

(-1.41, 1.13)

(-0.80, 0.55)

-0.17*

-0. 27*

(-0.21, -0.14)

0.36

(-0.31, -0.24)

0. 68

-0.42

(-1.42, 0.70)

Environment

-0.08

(-0.36, 0.16)

-0.67

(-1.46, 0.09)

-0.09

(-1.59, 1.30)

0.99

(-0.44, 2.68)

-0.11*

(-0.13, -0.09)

0.41

118

(-0.16, -0.10)

0.24

118

School Voucher

1 3

118

N

Bootstrapped confidence intervals in parentheses

* indicates significance at p < 0.05

-0.10

(-0.35, 0.20)

-0.15

(-1.24, 1.09)

0.92

(-2.03, 3.56)

-0.13*

Table 1: CVP Model Regression Table

Ira q War

Free Trade

).10

0.13

(-8.18.1 o-5, 0.19)

(-0.11, 0.40)

).02

-4.76*

Low Income Opinion

(-0.3 3, 0.32)

(-7.65, -1.57)

- 0.41

6.79*

Middle Income Opinion

(-1.0 9, 0.21)

(1.63, 11.62)

).28

-1.58*

High Income Opinion

(-2.83, -0.10)

(-0.3 1, 0.95)

-( .05*

-0.27*

Republican senator

(-0.0 7, -0.02)

(-0.31, -0.22)

0.42

Adj R 2

).07

123

123

N

in

parentheses

intervals

confidence

Bootstrapped

* indicates significance at p < 0.05

Intercept

Immigration

0.87

(-0.96, 2.19)

-0.72

(-5.33, 4.85)

-2.15

(-7.46, 2.31)

1.94

(-0.25, 3.88)

0.34*

(0.27, 0.42)

0.31

116

Federal Health Insurance

0.07*

(0.03, 0.11)

-0.09

(-0.41, 0.23)

0.50

(-0.39, 1.44)

-0.59*

(-1.20, -0.02)

0.04*

(0.03, 0.05)

0.21

118

The only positive and statistically significant results were found for senators' responsiveness to low income opinion on minimum wage and middle income opinion on free trade. A

ten percent increase in low income opinion against raising the minimum wage corresponds to

a 13.7 percentage point increase in the likelihood of their senators voting in the conservative

direction. This is contrary to Bartels' finding that senators only responded to the preferences

of the wealthy.

Negative and statistically significant effects were found for the middle income opinion for

37

banning gay marriage, low and high income opinion on free trade, and the wealthy opinion

on federal health insurance. It is not likely that the senators are actively choosing to do

the opposite of a particular income group's opinion. Most likely the senators are voting in a

position that is most dissimilar to this income group opinion for other reasons.

Figure 5

Minimum Wage

N1

0

U.

0

A

0A

A

*

A

A

A

0

A

A

A.

.rm1

gA.

.02

U

a

goo

EU

me

a0-

0

*

MU

C/)

M

U

a

0

opU

Eg

as

0.U .

0

~

*~