IIII P E

advertisement

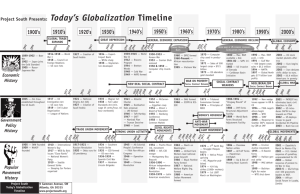

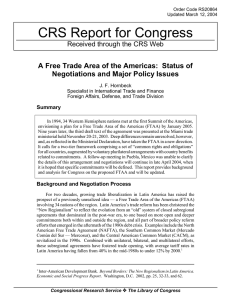

ISSUES IN INTERNATIONAL POLITICAL ECONOMY MAY 2004, NUMBER 53 Free Trade Area of the Americas: How to Screw Up a Perfectly Good Proposal Sidney Weintraub When President George H.W. Bush first proposed a hemispheric free trade area from Alaska to Tierra del Fuego in June 1990, the idea was greeted with considerable enthusiasm in Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC). The hemispheric countries that had reservations kept them mostly to themselves. Now, 14 years later, the Free Trade Area of the Americas (FTAA) is on life support—not dead, but its survival uncertain. It is worth asking why this change took place. The procedure set up following the Santiago, Chile, summit of 1998 led to scores of meetings of ministers, vice ministers, and negotiators in the various functional areas that were to be part of the FTAA. A deadline of end 1994 was put in place for completing the negotiations. The process seemed to be on track. The countries themselves, and the IDB on its own initiative, even considered what the administrative structure of the FTAA would look like. All of us, it seems, were a bit naïve. First, some background. When the proposal was made, most LAC countries had only recently shifted away from an import-substitution trade model, which downplayed the importance of exports, to a policy of export-led growth. Alongside this export pessimism, most LAC countries did not encourage inward foreign direct investment (FDI) based on concern that such investment would limit their control of economic policy. This unease over FDI was discarded after 1982 when Mexico came hat in hand to Washington seeking debt restructuring. LAC countries learned that the need to obtain creditor concessions on debt servicing truly frustrated their development, and the “lost decade” of the 1980s ensued. Some negative aspects of the FTAA process were not fully understood—certainly by me, but I was not alone. One was the weak leadership shown by the United States for many years, and this led many LAC countries to wonder just how serious the U.S. initiative was. Much of this skepticism remains to this day. Brazil’s tenacity in seeking to limit the extent of any hemispheric free trade agreement was not immediately apparent. Lula, before he formally became president, openly stated his belief that the United States was pushing the FTAA in order to gain dominance over the hemisphere, but his government’s position became subtler once he was in office. The timing of the Bush proposal was thus ideal. My judgment at that time was that hemispheric free trade would come into existence. The expectation was fortified when the Clinton administration renewed the idea at the Miami summit of 1994. A schedule for amassing the factual base of country trade programs was established using three hemispheric organizations as the virtual secretariat—the trade unit of the Organization of American States, the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB), and the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean. The information gathered in that process was more complete about hemispheric practices than had ever existed before. All of the data were made available on accessible Web sites. Yes, Brazil supports an FTAA, but with modifications. The two most important Brazilian conditions that emerged were the need for U.S. concessions in agriculture and a slimmeddown version of the scope of the agreement. I will come to this second issue later. The Brazilians surely understood that it would not be possible for the United States to negotiate sharp reductions in domestic agricultural subsidies in a hemispheric agreement, but that this issue was appropriate for the agenda of the Doha round of negotiations in the World Trade Organization (WTO) where all the developed countries would be involved. Nevertheless, the Brazilians persistently raised the subsidy issue in the FTAA context. The agricultural issue may take on new life now that the European Union (EU) has indicated its willingness to put all William E. Simon Chair in Political Economy • Center for Strategic and International Studies 1800 K Street, N.W. • Washington, D.C. 20006 • Tel: (202) 775775-3292 • Fax: (202) 775 775-3199 • www.csis.org its agricultural export subsidies on the table in the WTO negotiations if the United States does the same for export credits and food aid, and Canada, Australia, and New Zealand make their use of agricultural marketing boards part of the global agenda. hemispheric countries will have preferential trade relationships with the United States. In addition, individual hemispheric countries will continue to have separate bilateral preferences with each other. Instead of a unified hemisphere, we will have a divided hemisphere replete with spaghetti. Just about all trade policy players give pride of place to completion of the Doha round rather than to regional or bilateral agreements. In light of the May 10 EU letter to the other WTO negotiators, the prospects for completion of the Doha round look much more promising than before, although by no means certain. This brings me to the nub of this essay. If the WTO round is completed, is there any need for the FTAA? The simple answer is perhaps not, especially if the tariff cuts in the Doha round are substantial and thereby reduce the extent of preferences in current preferential agreements that abound throughout the world. If this comes about it will be because Brazil did not want a full-fledged FTAA, and the United States opted for a raft of bilateral FTAs. An FTAA “lite” could complicate this situation further in that the reciprocal rights and obligations of its adherents would be less comprehensive than in their separate bilateral FTAs with the United States—although this may be mitigated depending on how many countries join in a comprehensive plurilateral agreement under the Miami framework. However, most tariffs will not go to zero after Doha. About two score preferential trade agreements exist just among hemispheric countries, including those in existence and contemplated by the United States; the current complex system of overlapping discrimination and restrictive rules of origin will not automatically disappear. The most salient argument for the FTAA is that it would create a single structure of preferences and rules of origin for the 34 countries negotiating the FTAA, or for as many who wish to join in the agreement. Getting rid of the spaghetti that now exists would be a most welcome accomplishment. The task of negotiating the FTAA has been made abominably difficult by the framework agreed to in a ministerial meeting in Miami in November 2003. This calls for a common set of undertakings by all the negotiating countries and then discretionary adherence to obligations for all the rest. The Brazilian stress has been on market access (especially lowering of tariffs) for the bulk of the common set commitments and less adherence by it on other areas, especially trade in services. This has been called FTAA “lite” or FTAA “à la carte.” The failure to obtain meaningful concessions in trade in services would greatly reduce the attractiveness of the FTAA for the United States. The Miami framework also would allow “plurilateral” agreements under which less than the 34 negotiating countries could conclude their own full-fledged (not “lite”) agreements. Other considerations should be noted. The United States has negotiated or is in the process of concluding free trade agreements (FTAs) with just about all Latin American countries other than Venezuela and the four Mercosur countries (Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay, and Uruguay). Mercosur and the EU may conclude their own FTA before the end of 2004. If all these deals go forward, this will set up a situation in which the four Mercosur countries have a preferential trade relationship with the EU, while most other The foregoing description may be unfathomable to the reader. I had trouble getting it straight. But that is what is happening. This, in essence, is my main conclusion. All the machinations and maneuvering are really complicating the trade structure in the hemisphere. I doubt that there is any basis for supporting an FTAA if the current process adds to rather than eliminates this complex web of cross discrimination and heaven only knows how many separate rules of origin. Traders will need experts to figure out the best country from which to ship goods to other countries in order to get the best tariff deal at the destination. The total structure that now seems to be playing out is likely to be unstable. If that is correct, this will at least provide work for another generation of trade negotiators to straighten out the mess. Issues in International Political Economy is published by the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), a private, taxtaxexempt institution focusing on inter international national public policy issues. Its research is nonpartisan and nonproprietary. CSIS does not take specific policy positions. Accordingly, all views, positions, and conclusions expressed in this publication should be understood to be solely those of the author. author. © 2004 by the Center for Strategic and International Studies. William E. Simon Chair in Political Economy • Center for Strategic and International Studies 1800 K Street, N.W. • Washington, D.C. 20006 • Tel: (202) 775775-3292 • Fax: (202) 775 775-3199 • www.csis.org