SOME ASPECTS by AREAS SCHAEFFER

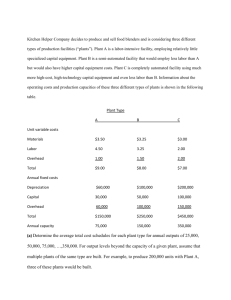

advertisement