by AT Nancyellen Hayes Seiden Bachelor of Arts

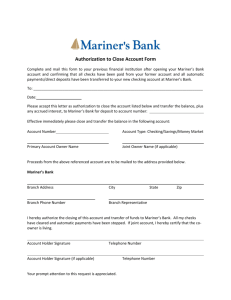

advertisement