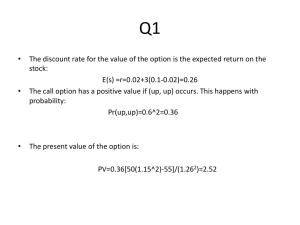

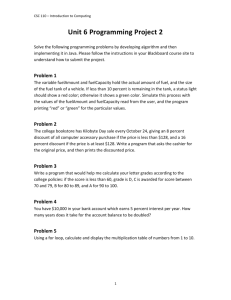

by (1973)

advertisement