UNITED NATIONS CONFERENCE ON TRADE AND DEVELOPMENT High-level segment of the

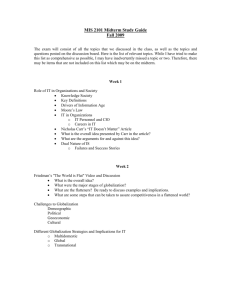

advertisement