IN MASSACHUSETTS by 1979 MASSACHUSETTS

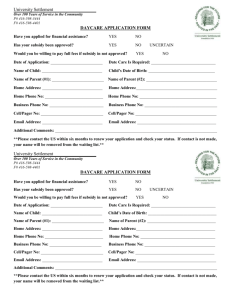

advertisement