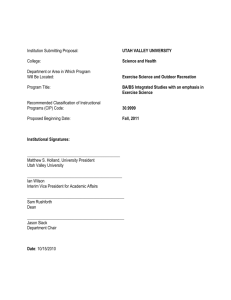

(1966)

advertisement