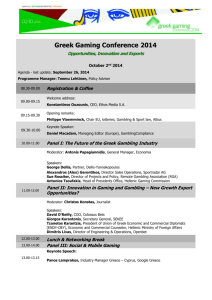

Working Procedures for the Panel of Gambling and Betting Services

advertisement