IDB C S T C

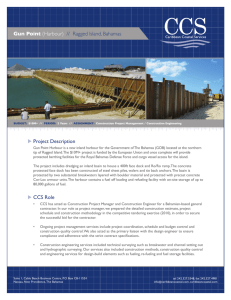

advertisement