RNM/OECS COUNTRY STUDIES TO INFORM TRADE NEGOTIATIONS: ST. VINCENT AND THE GRENADINES

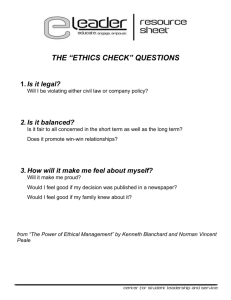

advertisement