Jamaica The Road to Sustained Growth Country Economic Memorandum Report No. 26088-JM

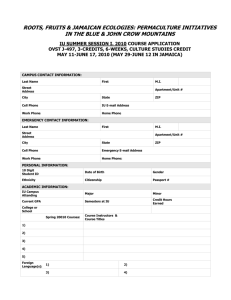

advertisement