s a au- [Finn]: a Finnish steam bath

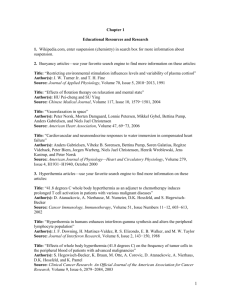

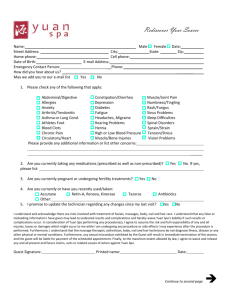

advertisement

![s a au- [Finn]: a Finnish steam bath](http://s2.studylib.net/store/data/010567747_1-af4bccfaa5a58eab3a5849603f09c373-768x994.png)