PLANNING (A Bachelor of Architecture, Hampton University by

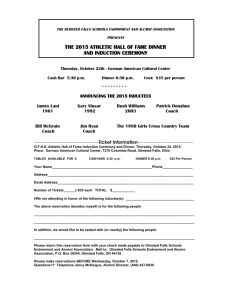

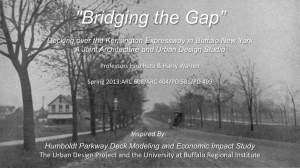

advertisement